National donor-advised fund sponsors — particularly those affiliated with for-profit wealth management firms — often claim that they “democratize giving” by making foundation-style grantmaking available to a wider range of donors.

But by blending their numbers with those of pass-through organizations like workplace giving funds and mass donation processors, they are making themselves look more egalitarian than they actually are.

Until we demand that donor-advised fund sponsors meet clear reporting and transparency requirements, they will continue to cherry-pick data to put themselves in an artificially positive light.

DAFs of different stripes

Donor-advised funds, or DAFs, essentially serve as miniature private foundations. Donors give money to a personal DAF account and can take an immediate tax deduction for that gift, since a DAF is technically a public charity.

The organization managing the DAF then gives the donors advisory privileges to recommend grants out of the DAF to whichever qualified charities they want, on whatever schedule they want.

DAFs are attractive to wealthy donors who want to get big tax deductions for charitable gifts — especially donors who want to offload appreciated complex assets like real estate and cryptocurrency without having to pay capital gains taxes on them.

And since there is no payout requirement for DAFs, the money can legally sit in them forever. As a result, the organizations managing DAFs, which are known as sponsors, are getting bigger, and bigger, and bigger.

But DAF sponsors come in different flavors. Some — including the country’s very largest — are nonprofit arms of commercial wealth management firms (like Fidelity or Schwab); some are workplace giving or donation processors, and some are community foundations or working charities.

The first two of these types of sponsors are very different, but are often lumped together in analyses of DAFs.

The sponsors affiliated with wealth managers typically market themselves to extremely wealthy people, often existing clients. Their DAF accounts are enormous, they are able to take in multi-million or even billion-dollar contributions at a pop, and the money can often take a very, very long time to flow out to working charities.

Workplace giving and donation processors, on the other hand, tend to take in very large numbers of modest contributions from everyday donors. They mainly serve as pass-through conduits, funneling the money relatively quickly back out to working charities.

DAFs are growing fast, then, not only because traditional national, community foundation, and single-issue sponsors have helped make them the preferred giving vehicle for wealthy donors, but also because technology firms are using them for mass donation processing.

Why commercial DAF sponsors would want to associate with donation processors

U.S. taxpayers pay for the charitable deductions that wealthy donors take for their gifts to DAFs in the form of lost tax revenue. But when these gifts languish in a DAF for years, or even forever, taxpayers get nothing back for this subsidy.

As taxpayers learn more about how DAFs work, they are starting to demand that DAF donors fulfill their end of the charitable bargain, and pay the money back out to working charities with all deliberate speed.

But some DAF sponsors, especially those affiliated with commercial wealth managers, have a lot invested — literally — in the status quo. So they use every opportunity to present DAFs as a benign tool accessible to a broad range of donors.

One way to do this is to pool their asset, grant, and account numbers with those of the genuinely more representative workplace giving sponsors and donation processors, and to report only on average account sizes and grant payout rates for this entire group of “national” DAFs.

By diluting their measures this way, big national sponsors are able to make themselves look more “democratic” than they really are.

The numbers — diluted

The annual DAF Report from the National Philanthropic Trust, or NPT, is a case in point. Analysts and journalists depend on this report for annual data on the country’s donor-advised funds.

The NPT report breaks down DAF sponsors into three types: national, community foundation, and single-issue (which may include working charities).

In 2022, national sponsors looked relatively good compared to the other types. They had an average account size of $86,194 (compared to an overall DAF average of $117,466), and paid out their grants at an average rate of 23.2 percent of their prior year assets (compared to a rate of 22.5 percent for DAFs overall).

The report highlighted the fact that the roughly $86,000 average national DAF account was well below the $547,648 average account at community foundation DAFs, pointing out that the average community foundation DAF account “is almost double that of Single-Issue Charities and nearly six times greater than the average DAF account size at National Charities.”

The implication is that community foundation DAFs, with their huge accounts, are used more by wealthy donors, while national DAFs, with their smaller accounts, are more democratic.

But are they really? The NPT has not responded to IPS requests to reveal which sponsors they analyze in their report or which categories those sponsors fall into.

The NPT’s analysis does include workplace giving sponsors, but we don’t know whether it includes donation processors. If it does, however, both of these types of pass-through sponsors would almost assuredly be falling into the national category. And both would dilute the averages for the rest of the national DAFs.

We wondered what the numbers would look like if we could separate the pass-throughs from the nationals and look at each by itself.

The numbers — undiluted

Because, again, we have no way of knowing which sponsors the NPT used in their report, for our own analysis we used data from sponsors themselves, which is publicly available from the IRS.

Overall, we found 1,401 sponsors that reported DAF assets on their tax returns in 2022. Of these, we identified 9 as workplace giving sponsors or donation processors, 48 as national sponsors, 632 as community foundations, and 713 as single-issue sponsors.

The workplace giving sponsors and donation processors we found are listed at the end of this post.

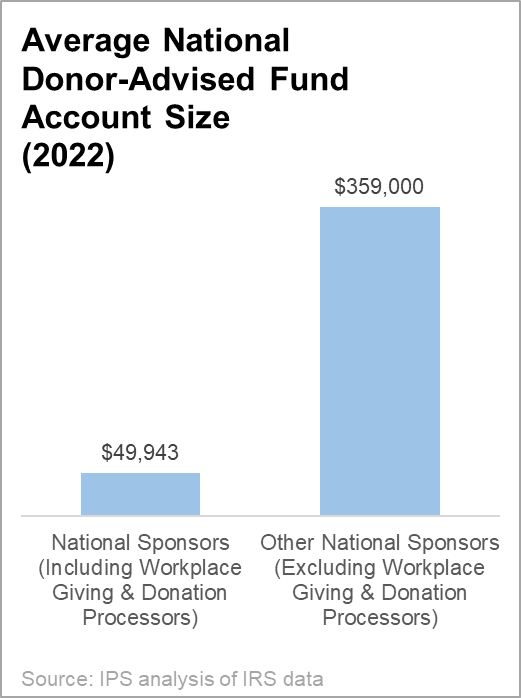

Together, the workplace giving sponsors, donation processors, and other national sponsors had an average account size of $49,943, much lower than the $540,290 average account size of the community foundation sponsors. But without the workplace giving sponsors and donation processors, the average account size for other national sponsors leapt up to $359,000, not nearly as far off from that of the community foundations.

It may be worth noting that NPT, which is a national DAF sponsor itself, had an average DAF account size of $1.5 million in 2022 — making it one of the greatest beneficiaries of the diluting, “democratizing” effect of including pass-through sponsors in average account size calculations.

Workplace giving and donation processor sponsors also tend to distribute about the same amount in grants each year that they take in in contributions, giving them an extremely high payout rate.

So mixing the workplace giving and donation processor sponsors with the national sponsors also gives the nationals a bump of about 2 percentage points in their aggregate payout. (The bump isn’t very big because the assets and account sizes of the donation processors are very low — representing modest donations from regular folks, not the giant donations of multimillionaires.)

It is important to keep in mind in all of this analysis, too, that all of these numbers are aggregate sponsor-level stats. We really need to know the median account sizes and payout rates for the individual accounts at each sponsor, as those would let us know what the typical account is doing, rather than just knowing the average of all of the accounts pooled together.

It may be, for example, that some DAF accounts are paying out at very high rates, while others — perhaps a surprisingly high proportion — may be paying nothing at all.

A recent report by the DAF Research Collaborative, for example, shows that there are big differences in payout and account size when you look at sponsors in aggregate versus when you look at medians.

But DAF sponsors are under no requirement to report anything about individual DAF accounts, and have blocked any attempts to impose such a requirement.

Are DAFs really available to anyone?

While DAFs are less expensive to set up than private foundations, to position them as democratizers of philanthropy may be a bit of a stretch. The minimum starting balance required to set up a DAF at many of the largest funds in the country is $5,000.

Other sponsors, even small ones, require a starting balance of $10,000 or more. And once a DAF is established, donors are subject to annual management fees and minimum additional deposit requirements.

Back in 2017, economist James Andreoni used IRS data to estimate the average income levels of people giving to DAFs. He determined that the income level of the typical DAF donor is staggeringly high — anywhere from $1.3 million to $2.1 million depending on the methodology. And, he said, the wealthier a person is, the greater benefits they will reap from having a DAF.

At the time of Andreoni’s analysis, there were just 234,000 people in the United States with at least $2 million in income. If the typical DAF donor was indeed a member of this group, it means they came from the most elite top 0.1 percent of income earners — hardly a representative population. And these estimates assume that every donor has only one DAF account; if donors have more than one DAF account, as is usually the case, then the higher those predicted income levels would be.

It’s high time for DAF reform

National sponsors are taking the most fire from those who want to see more DAF accountability, so it’s understandable that they would want to make themselves look better any way they can. But national sponsors are taking that fire because they have the most DAF assets and they rake in by far the most DAF donations every year.

In 2022, in fact, 9 of the top 20 charities in the U.S. were national DAF sponsors.

For this reason, it may not be an accident that NPT’s report chose to highlight account size comparisons between national and community foundation sponsors in 2022. That year, community foundations stood out as the only sponsors that increased their grantmaking overall, even as their assets and incoming contributions went down — perhaps making it even more necessary for the national sponsors to try to find a way to look less self-serving.

When tobacco, pharmaceutical, or financial services companies produce their own reports on the products they represent, journalists and the public are able to see through the spin. We need to look at industry-funded reports about donor-advised funds — like that from NPT — with a similarly critical eye.

And inter-sponsor competition aside, all sponsors are taking advantage of a charitable system tilted in favor of donor-advised funds — a system that offers DAF managers significant benefits with almost no transparency and accountability.

In addition to the nine national sponsors among the top 20 charities in 2022, two more were community foundation sponsors. And donation processors and workplace giving sponsors are not necessarily fault-free, either.

The donation processor PayPal Giving Fund, or PPGF, is a prime example. PPGF receives the donations for most of the largest crowdfunding platforms in the country, including GoFundMe, eBay, Facebook, and Instagram.

What most donors to these platforms may not realize is that their contributions aren’t actually going immediately to their chosen charities — they’re going to PPGF, which then distributes the money back out on their own timeline.

And if the charity you have chosen isn’t registered with PPGF — which is the case for all but a small number of nonprofits — your contribution won’t go to that charity; it will go instead to a charity chosen by PPGF.

In 2017, 23 attorneys general filed a class action lawsuit against PPGF about these issues. PPGF settled the lawsuit in 2020, promising to make its processes clearer to donors, but the process is arguably just as opaque as before.

Unfortunately, our charitable system is stacked in favor of DAF sponsors, no matter the type. Every year, DAFs divert more giving from working charities, and the assets of the largest sponsors are growing at lightning speed.

Without intervention, these DAFs will cut ever deeper into the charitable pie. And without more transparency, we will have no way of knowing if or how the taxpayer-subsidized revenue building up in DAF coffers is being used for our benefit.

We need to have meaningful reform now to increase both the outflow and the accountability of DAFs.

Our list of workplace giving sponsors and donation processors

The DAF sponsors that we included as either workplace giving sponsors or donation processors are the following:

Note on methodology: We looked at sponsors that had any DAF assets in 2022, the most recent year available from the IRS and the most recent year in the NPT report. Because our data set is likely different from that of the NPT, our numbers will be slightly different, too, but this is the only way for us to get any kind of independent, reliable picture of DAF accounts by sponsor type.