In his Cairo address, President Obama boldly asserted a broad commonality between the United States and a quarter of humanity: “America and Islam are not exclusive, and need not be in competition. Instead, they overlap, and share common principles — principles of justice and progress; tolerance and the dignity of all human beings.”

In his Cairo address, President Obama boldly asserted a broad commonality between the United States and a quarter of humanity: “America and Islam are not exclusive, and need not be in competition. Instead, they overlap, and share common principles — principles of justice and progress; tolerance and the dignity of all human beings.”

Yet the most striking part of Obama’s speech contained not his own words but those of others: “I am also proud to carry with me the goodwill of the American people, and a greeting of peace from Muslim communities in my country: assalaamu alaykum.”

In conveying this salutation of peace from American Muslims, the president did more than link the promise of American ideals to the piety of the Islamic faith. He pointed to the existing reality of a community that he believes exemplifies his message — Muslims living and practicing freely in the citadel of the Western world.

Islam and the United States

There are 3-7 million adherents of Islam in the United States, about two-thirds of whom are first-generation immigrants. On the whole, Muslims hold above-average incomes and enjoy more liberty as a minority here than that available to them as part of a majority in most Muslim countries.

But these are only the broad, faint outlines of an unfinished montage, some pieces of which are gripped in uncertain, nervous hands — including my own.

As a young American Muslim raised in this country, I’m not sure whether America is willing to truly incorporate Muslims or merely assimilate us; whether the nation views us as a potential pillar or a probable fifth column. Fine phrases about freedom cannot, after all, gild the discrimination, suspicion, and occasional outright hostility we have faced here amid the sustained neoconservative assault of the past decade.

Subject to open suspicion and closed minds, the conscious American Muslim learns to reach with a long arm for knowledge about his religion, its teachings, its history, and its richness. This knowledge isn’t caked in rote rituals delivered downstream by the diluting currents of reflexive custom, as is so often the case in Muslim “home” countries. Instead, it’s sought out with covetous hands and seized fresh from thrashing waves underneath which it threatens to disappear in the foam of assimilation.

But it would be dishonest to pretend that this ceaseless sense of embattlement and isolation is healthy, or even sustainable. We intuitively yearn for the familiar — that which links not only past and present, but our particular past and our particular present — to achieve a sense of belonging at the deepest levels, those of community and faith. Without these, we are lost.

Young American Muslims in particular must often choose between two outcomes: a meek retreat into an insular Islam divorced from one’s surrounding community, or a tight embrace of an America that is wedded to anti-Islamic animus. Neither accords with the president’s vision of inter-civilizational exchange, and each involves a profound loss, either of self or of community.

But there is an alternative.

Straddling the Divide

Conscientious young American Muslims born or raised here can jettison the dichotomy of dueling identities and adopt the notion of dual agency: We are both members of the Ummah (Muslim community) and citizens of this country, capable of influencing both Islamic and American cultures by way of example and action.

In recognizing its particular joint membership, the American Muslim community can improve the future of Islam and its relationship with the West without sweeping aside the Islamic past or being swept away by the Western present.

It is easy to make a statement so broad that it invites only further questions: What practices and customs are integral to Islam, and what has simply coexisted with Islam in various societies? What needs restoration, and what needs reformation? The very term “Islamic renaissance” betrays an obsequious tendency toward unthinking imitation, but a carte-blanche rejection of change because it resembles a Western development is puerile. What, then, can be done?

I have no profound solutions or pat answers, only a small story about a cap — or, in Pashtun parlance, a pakol — which might in some small way illuminate the contours of the questions themselves.

The Hat

For the past few winters, I have been content to don simple winter hats to help cope with the cold. While they serve their purpose, they also tend to look like dollops of ice cream plopped on the head.

When I lost my latest winter hat, an occurrence as predictable as the onset of winter itself, I was determined to find a more dignified piece of headwear.

Pondering alternatives, I recalled a saying of the Prophet Muhammad found in philosopher Frithof Schuon’s Understanding Islam: “The turban is the frontier between faith and unbelief.” I did not consider wearing a turban, per se, partly because I could not much relate to it culturally. But I scanned my memory for something somewhat closer to my heritage and recalled a circular, thick, tough wool hat I occasionally came across during my childhood summer sojourns in the port city of Karachi, Pakistan.

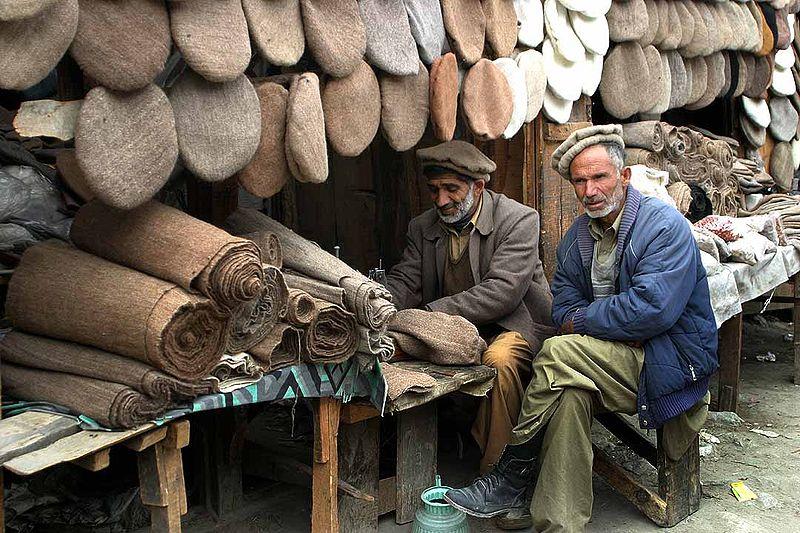

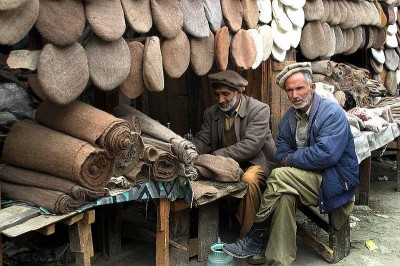

A quick Google search turned up what I was looking for: a pakol, commonly worn by Pashtun men in northern Pakistan and southern Afghanistan.

While I took a liking to its appearance, I was especially glad to find a piece of attire linked to the country of my birth and worn by people of my faith. I placed an order over the Internet.

However, it was not long before a sense of unease slowly crept into and then enveloped my mind.

For the past seven years, iconic images of bearded villains donning headwear of one kind or another have been beamed into the retina and burned into the memory of millions of Americans. Although the mere sight of a bearded, brown “towel-head” no longer inspires violence, as it did in the weeks following the September 11 terrorist attacks, a negative association still persists, occasionally with ugly consequences — like a bully’s attempted eye-gouging of a Sikh turban-wearing 18-year-old classmate two years ago in New York.

A more specific concern also commanded attention: the withering gaze of the war hawks had shifted from the Tigris and Euphrates to the mountainous and rural areas straddling the Pak-Afghan border, which is mostly inhabited by Pashtuns and which is also, after decades of neglect, mismanagement, and provocation, in the grip of Taliban militants.

By wearing a pakol, would I be conflated with current war targets?

I resolved not to let these anxieties influence my choice. If I could not be graced with the presence of the Prophet Muhammad in my lifetime, or that of a society shaped in part by the revelation he brought, I could at least symbolically recognize his wisdom in a public way.

Pakols and Kalashnikovs

As I anxiously waited for this newfound symbol of identity to arrive at my doorstep, halfway around the world the disturbing consequences of Pakistan’s appeasement of the Taliban had already become painfully clear: in the plaintive cries of a young girl beaten and ground into dirt before a circle of silent men, in the blood splashed across a mosque where two youngsters were executed for supposedly daring to elope, in the rubble of a school and the corpses of children whose inner lights were extinguished inside. In these spaces, the Taliban declaimed as they donned pakols and shouldered Kalashnikovs, lie the sweet fruit reaped by pure and genuine Islam.

The Prophet Muhammad, were he alive today, might recognize some passing similarities in attire with those now marauding across northern Pakistan and Afghanistan. But would he recognize anything else in them save the very iniquities — ignorance, illiteracy, misogyny — that, according to the accounts of his closest companions and Islam’s earliest converts, he strived to replace in his own lifetime?

The Taliban’s inversion of core Islamic values aborted my embryonic ambition to establish a putative link between myself and my heritage.

True, I am no Pashtun tribesman, nor have I ever pretended to be. There is also nothing intrinsically Islamic about the pakol, or many other aspects of Pashtun culture. And not all Pashtun are Taliban. But for me this was all quite beside the point. I wanted to wear the pakol out of an aching need for a tangible link to Islam, in a country where Islam is almost invisible — unless it is being vilified. Those committing harsh atrocities in the name of God had cut short my attempt to achieve this bond.

American Muslims often struggle to express a desire for a link to the faith at a most basic level, sometimes with curious and scattershot results. Some men wear jewelry emblazoned with Arabic calligraphy extolling God, and some women eschew headscarves because they attract rather than deflect attention, opting instead for modest dress alone.

Whatever the particulars, adherence to an Islamic identity establishes a degree of closeness among other Muslims. However, as I discovered through experience, it is not necessarily helpful to reach reflexively for symbols of another time and place in an attempt to avoid slipping into an imagined generic mass.

An alternative path may be best illustrated by way of analogy. A Muslim closely observes all the ritual dips, bows, and kneeling of salaat (prayer) not because these acts instantly bring about a deep spiritual connection. Rather, when combined with sincere belief, such rituals help to cultivate an internal state that is more open to connection with God.

Along similar lines, American Muslims might invite themselves to collectively craft traditions reflecting their own understanding and experience of Islam — not because this will instill a profound sense of camaraderie on command, but because it can form a protective boundary for the fledgling American Muslim community within which their Islam can more fully develop.

Encouraging its own unique norms would place the community neither outside America nor outside the Ummah. It would instead situate it in an overlapping space comprising the best of each world, one infused with ideas and practices that lie within the sphere of civility and the realm of reason and free from the extremes of anti-Islamic miasma and anti-Western zealotry.

These protective boundaries might comprise a new, modern “frontier between belief and unbelief” for Muslims. If Muslims here do choose to lead, practicing a religion of tolerance in a land of tolerance, they may protect even as they are protected. They can show fellow Americans an Islam that is not a battle cry for fanatics in some exotic land, but a religion practiced by their neighbors. At the same time, they can familiarize fellow Muslims with an America that is not an arrogant entity quick to unleash war, but a country of their own neighbors.

Uniquely positioned to serve as a bridge between Americans who desire lasting security and the outside Muslim world which seeks genuine respect, Muslims here can serve as the great inter-civilizational fulcrum of our time.

Overcoming Islamophobia

Some here and abroad will doubtlessly mock such thinking with open contempt. Islamophobes and some “Islamists” alike are curiously united in their conviction, unshaken by ample evidence furnished over 1,400 years, that Islam is somehow fixed and unchanging for followers across time and space. For the deaf, even the most melodious tune registers only as uninterrupted silence.

But for the rest of us, there lies another, greater path. The Poet of the East (Shair-e-Mashriq) Muhammad Iqbal, whose thinking inspired the creation of Pakistan, once reminded Muslims that “a hundred new worlds” lie within the Qur’an’s verses, and that for the man of faith, “When one age becomes decrepit upon his body/ The Qur’an can yield him a new one.”