Most of us want to live rich, full lives. What do we mean by that? We don’t mean get filthy rich. Yes, most of us do seek economic security, but we don’t wake up every morning scheming to make ourselves a grand private fortune. We endeavor to be rich in a broader sense. We want to experience the world, meet interesting people, learn from some and inspire others.

All this becomes harder when the societies we live in become ever more unequal. The wider the economic gaps that divide us, the smaller the diversity of our social universes become, the fewer new things and people we experience.

We tend to know this reality, feel this reality, in our guts. We see acquaintances who have suddenly started earning twice as much as we do drift out of our social circles. Or the reverse. People we know who’ve hit hard times begin, over time, to make themselves scarce.

So we end up seeing the same faces, going to the same places. Our isolation — from the rich, full lives we lust for — deepens.

How deep into society has this isolation gone? Can we quantify how growing economic inequality is changing the pattern of our daily lives? Researchers at MIT’s Media Lab and Spain’s Universidad Carlos III de Madrid think we can. They’ve recently unveiled online a project they’ve dubbed the Atlas of Inequality.

The core insight behind the project’s design: “The way we experience economic inequality in cities is impacted by where we go, not just by where we live.”

The researchers here used the high-tech magic of smart phones and location software to track where people go in selected major U.S. cities. They’ve divided urban physical space into 80-by-80-foot blocks and then calculated, by tying in census data on where people live, the socio-economic backgrounds of people who share a particular physical space for an appreciable time period.

The bottom line: For physical spaces that range from coffee shops to movie theaters, the “Atlas of Inequality” can show a specific location’s level of economic segregation.

A coffeeshop, for instance, may serve an overwhelmingly high-income clientele (people from neighborhoods that average over $114,000 in annual income) or attract a distinctly low-income set of customers (under $67,000). Atlas of Inequality researchers are also tracking where medium-income ($67,000-$90,000) and upper-medium ($90,000-$114,000) individuals find themselves going.

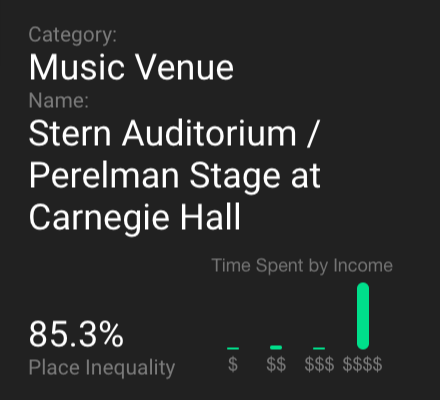

The datapoints collected — in the billions for each city studied — carry no actual individual names. The researchers “anonymize” their data, before analysis. But the Atlas of Inequality data do allow us to see the income diversity of the people who spend time in each tracked location, and the Atlas researchers give each location a “place inequality” score. The higher the score, the more a location draws visitors from just one or two of the four income groups the Atlas tracks.

Source: Atlas of Inequality

One example: The Stern Auditorium at Carnegie Hall in Manhattan carries an 85.3 percent “place inequality” rating. The overwhelming share of the visitors to this venue come from the Atlas of Inequality’s highest income level.

The Atlas of Inequality research team has so far posted online data for only Boston and New York. But other major cities will have data online as well. The Atlas may eventually allow us to track not just how economically segregated our cities have become, but how levels of economic segregation are changing over time.

“Segregation is hurting our societies and especially our cities,” notes the physicist Esteban Moro, one of the Atlas of Inequality’s key investigators. “But economic inequality isn’t just limited to neighborhoods. The restaurants, stores, and other places we visit in cities are all unequal in their own way.”

“We are living together,” adds Moro, “but living apart.”

Moro is hoping the Atlas can encourage more people to start breaking down that economic isolation. He’s urging people to “please cross the street” and venture into places they normally don’t frequent.

Good advice. Even better advice: Let’s get serious, as a society, about creating a much more equal distribution of our income and wealth.