Every February, the Labor Sustainability Network coordinates Transit Equity Day, a nationwide day of action that highlights the importance of equitable public transit in ongoing struggles for civil rights.

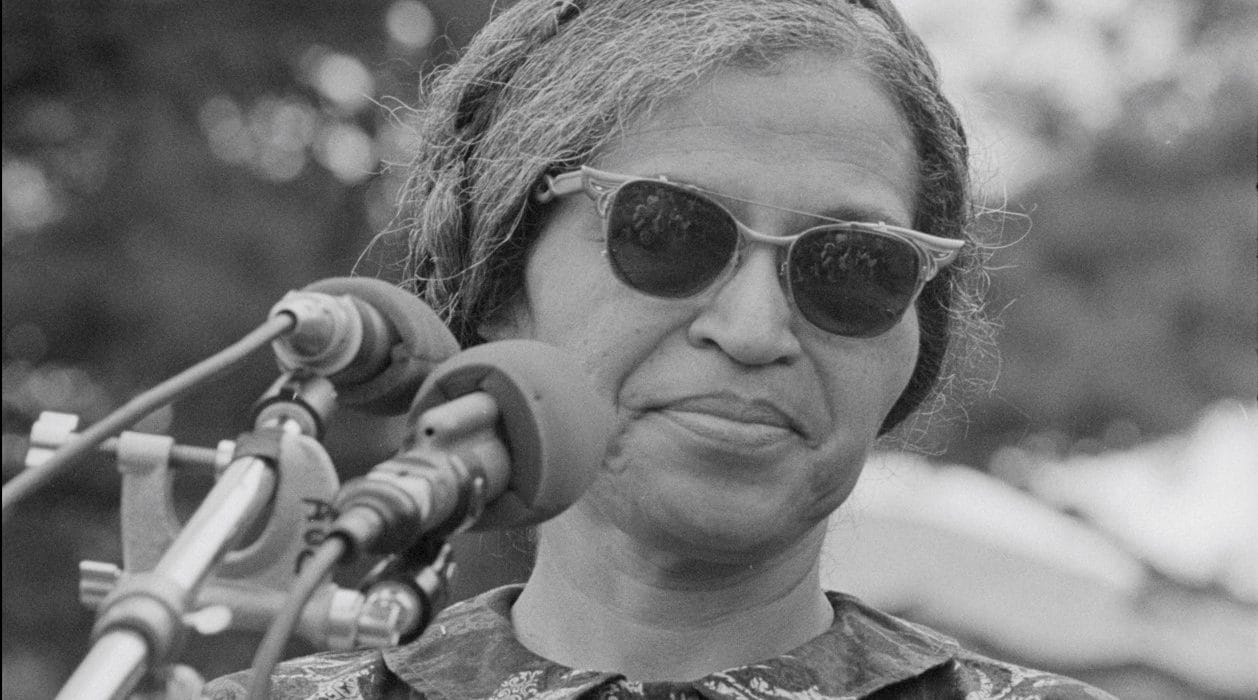

This year’s action, on February 5, falls on the day after what would’ve been the 111th birthday of Rosa Parks. Born in Tuskegee, Alabama, Parks was a lifelong civil rights activist. When she died in 2005, she became the first woman in American history to lie in honor at the U.S. Capitol.

Though Parks’s work ranged from defending political prisoners to anti-war activism, she is often best remembered for her contribution to transit equity. Refusing to surrender her bus seat to a white passenger, her arrest sparked the 1956 Montgomery Bus Boycott. The 13-month boycott ended with a U.S. Supreme Court ruling: public bus segregation is unconstitutional.

Parks’s activism didn’t stop there. After moving to Detroit, she engaged in an “even more diverse” range of political activities — fighting for dignity, democracy, and racial justice until the day she died.

“The struggle continues,” Parks always insisted. “Don’t give up and don’t say the movement is dead,” remained her mantra.

One way we can honor Parks’s legacy is by continuing her struggle for transit equity. To do so, we must first survey the current landscape of transit inequity.

How transit remains segregated today

Today, transit segregation takes a different form: a public-private divide that burdens the working class and punishes the car-less.

In 1956, the same year of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, President Eisenhower signed the Federal Aid Highway Act, investing billions into the interstate system. This marked a milestone in infrastructure policy and a shift in infrastructure investments — cementing the United States as a “car country.”

Car-centric infrastructure continued to receive billions in federal funding while allocations for public transit were restricted to “capital investments” (i.e., new buses or rail lines). This meant that the majority of funds had to come from local and state governments — leaving public transit perpetually underfunded.

Crowded platform at 168th street in New York City after a water main break caused severe service disruptions. Photo: Susan Sermoneta, September 2011

Between 1950 and 2019, U.S. public transit ridership fell from 17.2 billion trips to 9.9 billion, despite a population increase of 177 million in the same period.

For many Americans today, mobility means reliable automobile access. Nearly 70 percent of Americans get to work by driving alone and almost half have no access to public transit whatsoever. Those with access aren’t much better off — 40 percent of buses and 25 percent of rail are in some state of disrepair.

But reliable automobile access is linked to class. Cars are costly: by using public transit, commuters can save between $12,306 and $16,837 annually. That’s a lot, especially for low-income Americans — who are more likely to take public transit than any other income group.

Take New Orleans for example. A third of public transit riders live in poverty, compared to only 9 percent of those who drive cars. Meanwhile, the median income of public transit riders is roughly half that of all commuters — $15,711 and $31,017 respectively. From Albany to Albuquerque, this disparity exists in most U.S. cities.

Yet public transit’s exclusionary design often disadvantages the very people who depend on it most. According to the Urban Institute, local governments tend to fund transit more generously in neighborhoods with lower levels of poverty and higher shares of white residents — despite poor people and people of color being far more likely to use public transit.

Emphasizing roads over public and active transportation, U.S. infrastructure policy created a two-tiered transit system in much of the country — granting mobility to the car-owning population while limiting that of the transit-dependent. The result: a subtler, more persistent form of transit segregation that would outlast Jim Crow.

In an essay published shortly after his death, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. commented on this emerging form of transit segregation:

“Urban transit systems,” King wrote, “have become a genuine civil rights issue — and a valid one — because the layout of rapid-transit systems determines the accessibility of jobs to the black community.”

“If transportation systems in American cities could be laid out so as to provide an opportunity for poor people to get meaningful employment,” he continued, “then they could begin to move into the mainstream of American life.”

The promise of public transit expansion

Determining access to employment, education, medical care, and more, transit is at the nexus of inequality. In fact, one Harvard study found that commute time is the most important factor in determining whether an individual can escape poverty. Yet this also means that, by reforming public transit, we can make significant progress on many fronts at once.

MARTA train arriving to a station in Atlanta. Photo: S. Davis, December 2018

In Dr. King’s home city of Atlanta, a 40 percent increase in service would translate to an 800 percent increase in the number of jobs reachable by transit within 30 minutes. And peer-reviewed healthcare journals have found that simply “expanding existing bus routes can serve as rapid investments to improve health outcomes.”

In 2022, federal spending on roads totalled $52 billion. We could transform public transportation with a fraction of that sum.

A 2020 analysis by the Urban Institute suggests that, with an additional $16.7 billion annually in federal funding, we could bring transit service in every U.S. urban area up to that of the Chicago region — doubling per-capita transit service throughout the country.

More good news: transit expansion is gaining popularity. Over the past five years, U.S. voters have passed more than 85 percent of ballot measures to fund public transit.

“These ballot initiative wins are a testament to the importance of local, state, and federal partnerships,” says Paul P. Skoutelas, president and CEO of the American Public Transportation Association.

This progress begins at the grassroots level. Winning its campaign for fair fares in 2018, New York City’s Riders Alliance expanded the transit access of over 700,000 low-income residents. And in 2023, a coalition led by Together for Brothers won free bus fares for all in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

From free fares to expanded service, initiatives to ensure affordable and accessible public transit are cropping up across the United States.

On Transit Equity Day, and the week that follows, activists are organizing events in dozens of cities — opportunities for anyone to begin their participation in the civil rights struggle for transit equity.

In the words of Rosa Parks, “The Struggle Continues.” Honor her legacy, and get involved.