By way of explaining the metaphor that serves as the title of his latest book, “The Black Box,” the Harvard scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. transcribes a conversation he had with his son-in-law after the birth of his granddaughter 10 years ago:

“Did you check the box?” I asked, apropos of nothing we had just discussed.

Without missing a beat, my good son-in-law responded, “Yes, sir. I did.”

“Very good,” I responded, as I poured a second shot of Pappy Van Winkle.

The box that Gates’s son-in-law checked on a birth registration form indicates that his granddaughter is Black, even though his daughter’s genetic admixture is 75 percent European, and his son-in-law is 100 percent European. In other words, as Gates notes, his granddaughter “will test about 87.5 percent European when she spits in the test tube.”

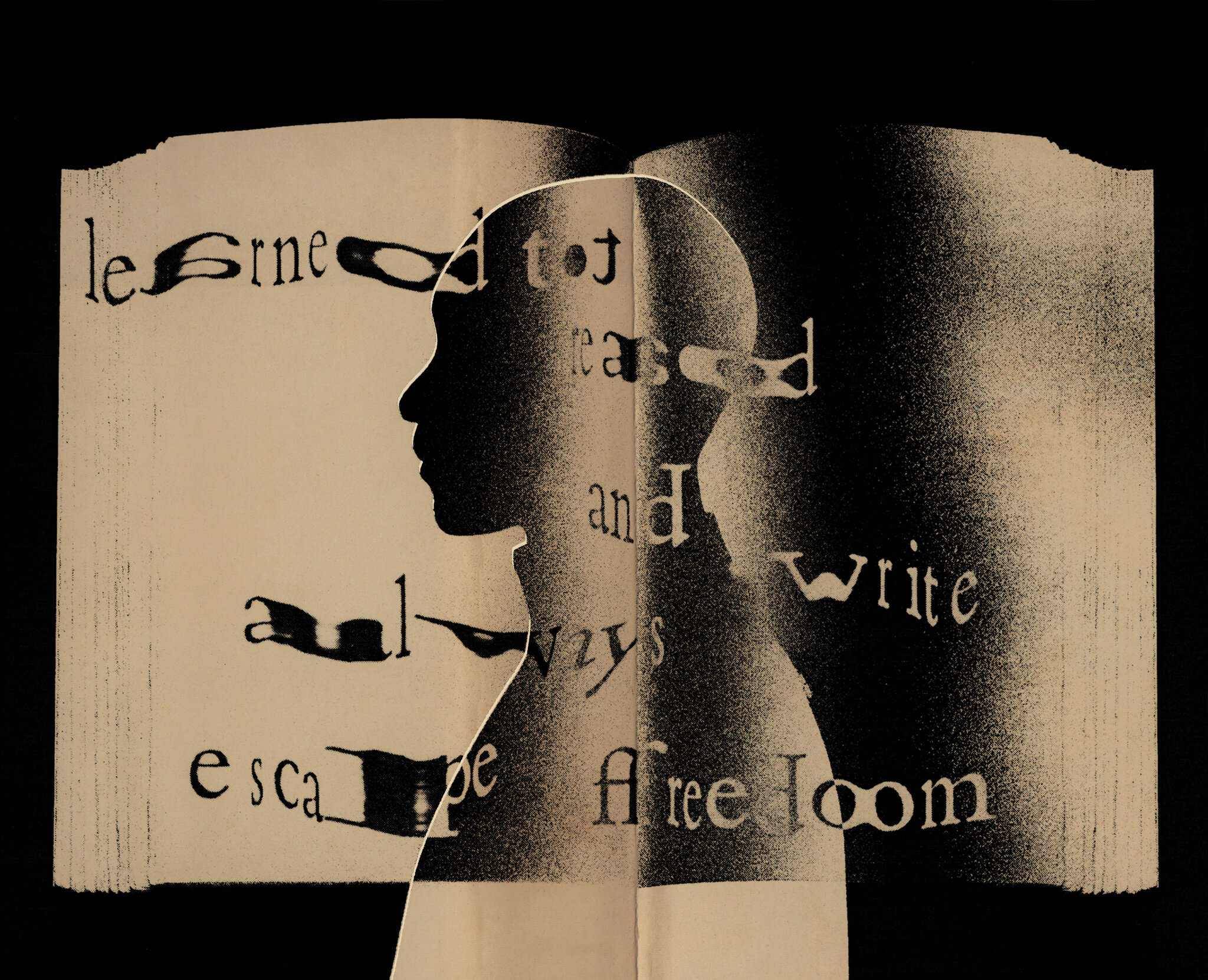

Gates offers this anecdote to suggest the arbitrariness of racial categories, and to focus our attention on the image of the box — a container that can function simultaneously as a “circumscribed enclosure” and a zone in which the confined can create a thriving “social and cultural world.”

“The Black Box” is based on lectures Gates has delivered for many years in his Introduction to African American Studies class at Harvard. From the beginning, he shows, African Americans have turned to literary forms to validate their humanity. He quickly sketches the childhood of Phillis Wheatley — her journey to America via slave ship, her rapid mastery of English — and the varied responses to her poetry, which she began to publish as a precocious teenager.