Gilded Giving 2022

How Wealth Inequality Distorts Philanthropy and Imperils Democracy

Chuck Collins | Helen Flannery

Introduction

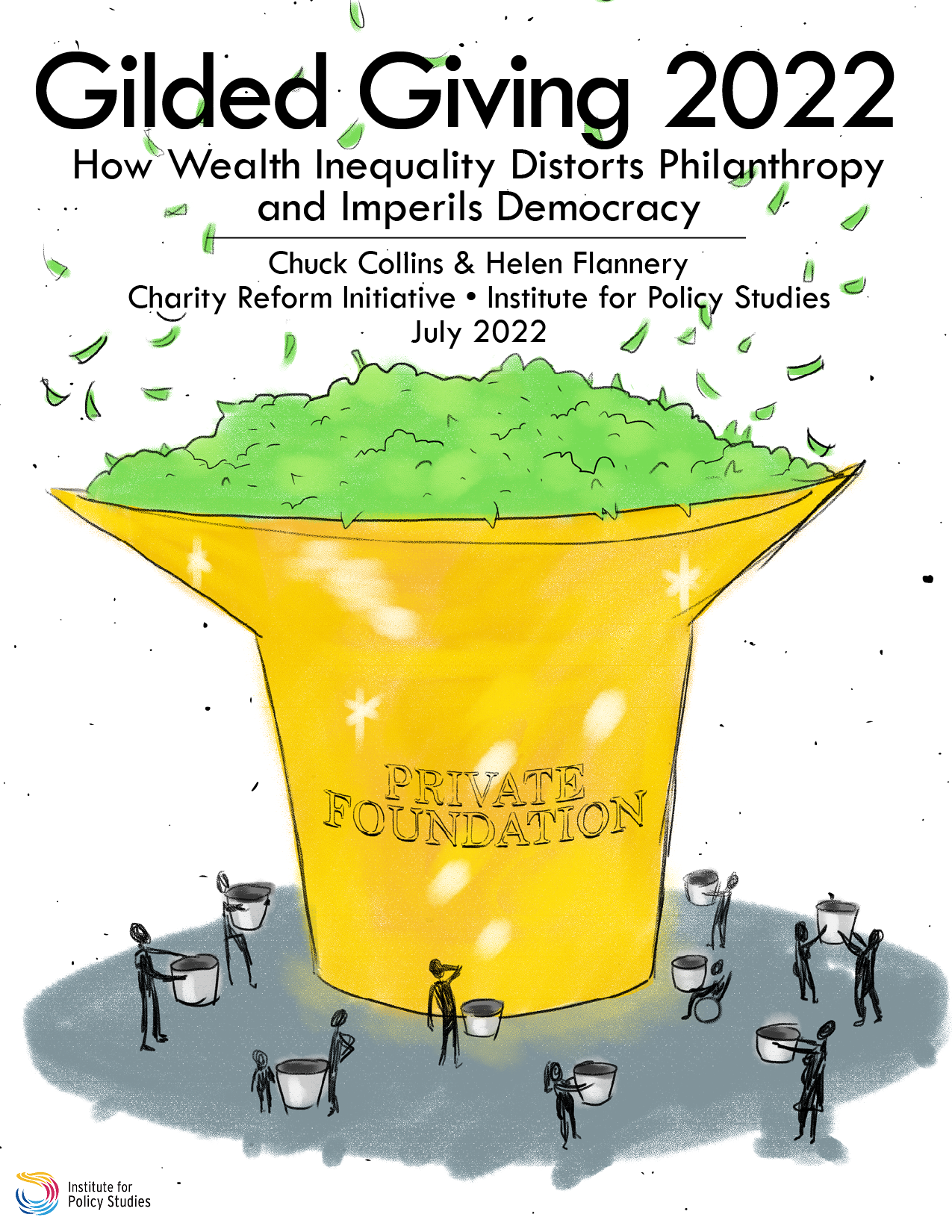

As inequality has grown in the United States, our nation’s charitable system is in danger of becoming a taxpayer-subsidized platform of private power for the ultra-wealthy. This poses risks to the independent nonprofit sector and our society as a whole.

Since our first edition of Gilded Giving 2016: Top Heavy Philanthropy in Age of Extreme Inequality, we have shown that charities are receiving shrinking amounts of revenue from donors at lower- and middle-income levels, and that they are more reliant on larger donations from smaller numbers of wealthy donors. And we have shown that wealthy donors tend to pour their dollars into foundations and donor-advised funds — charitable intermediary vehicles they control — rather than into public operating charities (i.e. active nonprofits on the ground).

This updated edition of Gilded Giving describes the extent of the capture of our charitable sector by the wealthy, the risks this poses, and how it has been exacerbated by the pandemic and other external factors. We also propose strong reforms that would reverse these trends and realign our charitable system to serve the public interest.

Key Findings

- Fewer than half of all U.S. households now give to charity.

- From 2000 to 2018, the most recent data available, the proportion of households giving to charity has dropped from 66 percent to just under 50 percent. These declines track indicators of economic insecurity such as employment, wages, and homeownership rates.

- The share of households that claim charitable deductions fell significantly after sweeping tax reform in 2017.

- Following the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the proportion of taxpayers who itemized their charitable giving fell from 25 percent in 2017 to just 10 percent after the bill took effect in 2018.

- The effect stuck: just 9 percent of households claimed charitable deductions on their returns in 2019. These changes most affected middle-income and affluent households earning $50,000 to $400,000 per year.

- Philanthropy is becoming increasingly top-heavy.

- In the early 1990s, households earning $200,000 or more accounted for less than 25 percent of all charitable deductions. By 2019, the most recent year available, this group accounted for 67 percent.

- The share of charitable deductions claimed by those at the top of the income scale has grown particularly quickly: households making over $1 million accounted for just 10 percent of charitable deductions in 1993, but accounted for 40 percent in 2019.

- Mega-giving is booming.

- In 2011, Giving USA’s threshold for mega-gifts was just $30 million, and gifts of that size or larger amounted to $2.7 billion.

- By 2021, just 10 years later, the mega-gift threshold had jumped to $450 million, and gifts of that size or larger added up to nearly $14.9 billion.

- The top two charitable causes of ultra-wealthy donors are their own private foundations and donor-advised funds.

- In early 2022, the Chronicle of Philanthropy published its annual list of the top 50 philanthropists in the U.S. Of the $25 billion in identifiable gifts that the group donated in 2021, 69 percent of it — more than $17 billion — went to private foundations.

- The second-largest chunk, more than $2.6 billion, went to donor-advised funds (DAFs).

- Both of these intermediary giving vehicles are favored by wealthy donors because of the significant tax advantages they offer.

- But funds may or may not flow from them to active charities in a timely way; there is no guarantee that they will fulfill the public interest.

- Contributions to donor-advised funds are skyrocketing.

- In 2020, for the first time, donations to DAFs caught up with contributions to private foundations; both received roughly $48 billion from donors that year.

- The largest single recipient of charitable giving in the U.S. for the past six years has been the Fidelity Charitable Gift Fund — a commercial DAF sponsor.

- For the past three years, six of the top 10 charities have been DAF sponsors.

- Gifts to private foundations and donor-advised funds now divert nearly a third of charitable giving in the U.S.

- Giving to private foundations has increased from 6 percent to 15 percent of all charitable giving since 1992.

- Giving to DAFs has increased from 4 percent to 15 percent of all charitable giving since 2007.

- Together, these charitable intermediaries now soak up 30 percent of all U.S. donations — more than quintupling their share of the charitable pie in less than thirty years.

- The public wants this system to be reformed.

- According to a new Ipsos poll, 81 percent of Americans do not believe that taxpayers should subsidize the wealthy to create perpetual private foundations. And the overwhelming majority also want private foundations and donor-advised funds to pay out funds to charity much faster than they currently do.

A Reckoning for the Charitable Sector

As inequality has grown in the United States, the nation’s charitable system is in danger of becoming a taxpayer-subsidized platform of private power for the ultra-wealthy. Already, the share of charitable deductions claimed by the very wealthiest households has risen steadily over the years.

Mega-philanthropists have intensified their influence over nonprofit giving with record-breaking splashes in the charitable world. The world’s richest men — Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, and Bill Gates — have all made multi-billion-dollar contributions to their own foundations and donor-advised funds, reducing their taxes by millions of dollars with charitable tax breaks.

Meanwhile, the share of regular Americans who give has steadily continued to fall, driving down the number of households who give overall.

Together, these trends leave charities more dependent on the preferences of the extremely wealthy.

What’s more, many of those wealthy donors increasingly prefer to give either to foundations they control, or to intermediaries like donor-advised funds (DAFs), which have no legal requirements to pay out to real charities over any period of time.

On top of all of this, the nonprofit sector has had to cope with two years of global pandemic, four years under a new tax law that discourages charitable giving, and many years of growth in for-profit investment options that further erode the tax advantages charities offer.

If we continue on our current trajectory, an ever-greater share of charitable dollars will be diverted into wealth warehousing vehicles rather than going to nonprofits serving critical needs. Wealthy donors will increasingly be able to use their charitable giving to opt out of paying their fair share in taxes to support the public infrastructure we all rely on.

And they will increasingly be able to deploy philanthropy to advance their narrow self-interests. Without intervention, ultra-wealthy philanthropists will rival even state and local governments in their ability to shape public policy.

This usurps the public’s power to define what problems are, which ones get addressed, and what their solutions should be. But as taxpayers, we subsidize the tax deductions taken by wealthy donors—giving us both the right and the responsibility to oversee and fix it.

We must take immediate action to remedy this before the independent sector loses its independence.

We urgently need to overhaul the rules governing philanthropy to discourage the warehousing of charitable wealth, to align tax incentives with the public interest, and to encourage broad-based giving across all segments of society.

Among other benefits, implementing these reforms would result in a significant amount of additional revenue flowing to working charities. We estimate, for example, that if foundations had a 10 percent minimum payout and DAFs had a three-year mandated payout between 2018 and 2020, at least $193 billion in additional donations would have flowed to nonprofits.

More recommendations are available in the full report, but here are some of the most important.

Reforms to Donor-Advised Funds:

- Require donor-advised funds to have a payout. We should require that DAFs pay out the entirety of any donations within three years after donations have gone into the fund, including any income earned on the donations during that time.

- Limit tax deductions for donations of complex assets to their sale value. To prevent inappropriately-inflated charitable deductions, we should base the deductions for donations of complex, non-cash appreciated property such as artwork, real estate, and cryptocurrency on their actual sale value, rather than their assessed value, and should delay that deduction until the year the property is sold.

- Increase DAF transparency and reporting. Donations to and from DAFs should be publicly disclosed and reported on an account-by-account basis. This could be done in such a way as to protect anonymous givers.

Reforms to Private Foundations:

- Increase the annual foundation payout requirement. We propose increasing the requirement to 10 percent of assets.

- Reform foundation payout exclusions. We should exclude both administrative overhead and grants to donor-advised funds from counting towards the foundation’s minimum payout requirement.

Reforms to Encourage Broad-Based Giving:

- Replace the itemized charitable deduction with a universal charitable tax deduction. We should implement a universal tax deduction for any households — not just those that itemize — that give more than 2 percent of their adjusted gross income to charity.

Reforms to Reverse Top-Heavy Philanthropy:

- Establish a lifetime cap on charitable gift deductions. To prevent donors from using charitable giving to reduce their taxes to zero indefinitely, we should implement a lifetime cap of $500 million on charitable tax deductions.

- Establish a cap on the charitable estate tax deduction. There is currently no limit on the amount of money that a person can pass tax-free to charity in their estate. To ensure that every person contributes to the costs of government, we should limit the estate tax charitable deduction to 50 percent of a donor’s estate.

- Levy a wealth tax on donor-advised funds and closely-held private foundations. We should implement an annual wealth tax of 2 percent on assets over $50 million that applies to donor-advised funds and to private foundations that are managed by founders or their family members.

Media Contacts:

Chuck Collins

chuck@ips-dc.org

(617) 308-4433

Robert Alvarez Pineda

robert@ips-dc.org

(916) 690-9896