Harry Belafonte has died at age 96.

The legendary civil rights activist and entertainer had a deep history with the Institute for Policy Studies — as an inspiration, as a partner in our work, and as a longtime member of our board. Along with people around the world, we are mourning his loss but also celebrating his life.

Here’s how Harry described his long journey with IPS at the 40th anniversary of our Letelier-Moffitt Human Rights Awards a few years ago:

(VIdeo by Laura Flanders)

“I’m amazed that after 90 years of life that I’m still here today with IPS, doing the work we set out to do… The work that IPS does is not only critical and important, but it has also put a light in places where only shadows at one time existed. They put a light on the places that the human family needs to be present — places they need to know about and people whom they need to embrace. So as long as there’s villainy, there’s a need for the work that we do. And I can think of us stopping that work only when villainy has ended.”

Harry concluded: “I don’t mind the work, because along the way I’ve met some remarkable people and had some glorious experiences.”

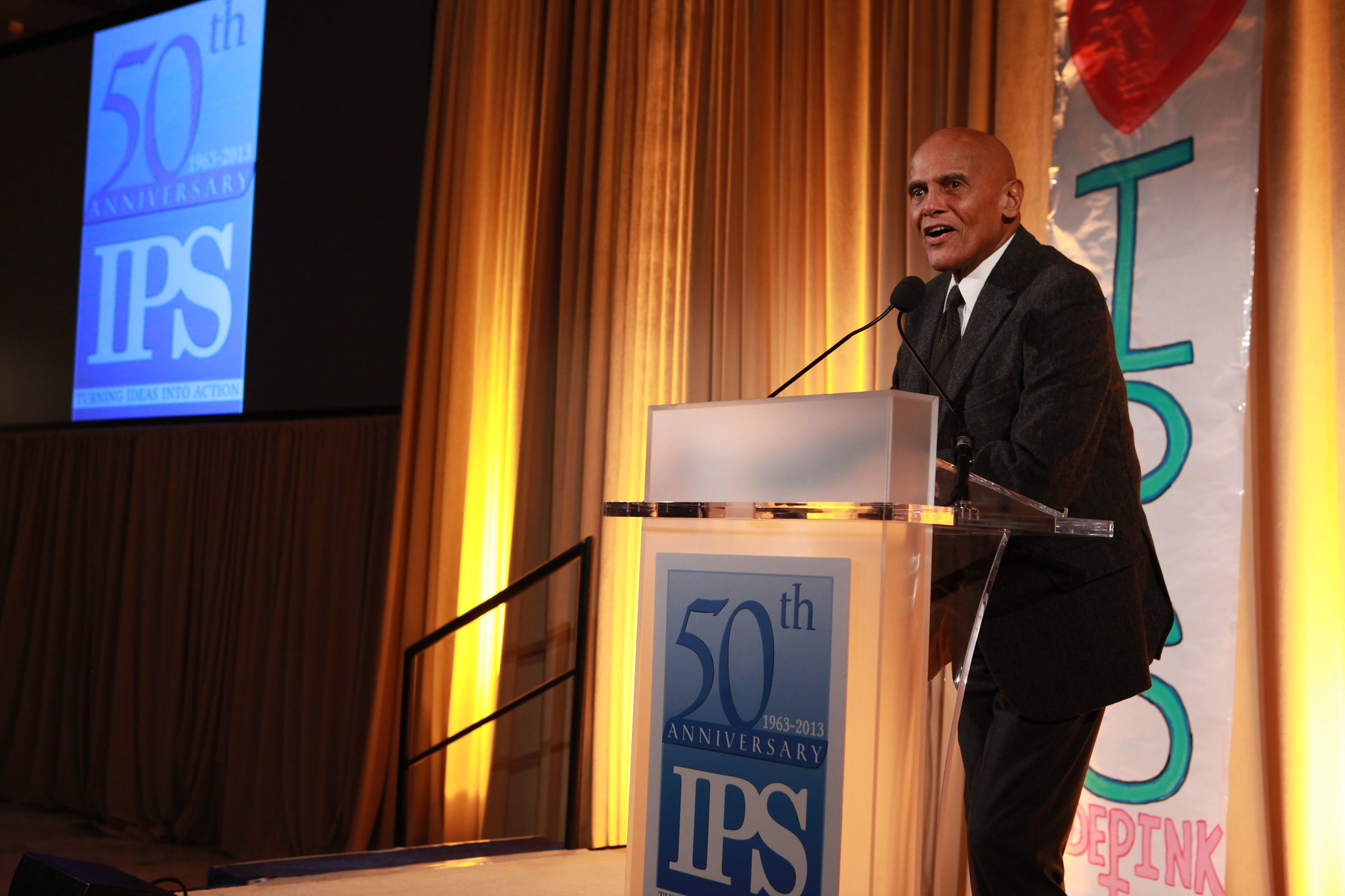

We felt the same way about our work with Harry. For more, you can watch Harry’s address at our 50th anniversary gala and watch him speak on a panel with other members of the IPS family in 2013.

Below, our IPS experts share their remembrances.

John Cavanagh, IPS Senior Adviser

Harry Belafonte with Phyllis Bennis (L) and John Cavanagh (R).

Harry always reminded us that he was an activist and cultural worker first, and an artist second, but he performed both roles at a level of excellence equaled by few.

Harry came into IPS through IPS’s Emmy-award winning senior scholar, the late Saul Landau, and the two were the best of friends in various schemes to advance peace and justice and in their travels together to Cuba.

When he joined IPS’s board in 2000, Harry said: “I am honored to offer my support to strengthen IPS’s mission of building a new political culture that nurtures full democratic participation and economic rights for all.”

And that’s exactly what he did.

Harry embraced IPS’s focus on putting ideas into action and engaged with IPS with gusto on economic human rights bus tours across the South and Midwest, on fighting the drug war in Latin America and on the streets of the United States, and in opposing unjust wars in Iraq and elsewhere.

I remember phoning Harry the day after 9/11. He immediately agreed to help refine and then get sign-ons for a statement we put together called “Justice, Not Vengeance.” As one of the six initiators of that landmark IPS document, Harry helped us get civil rights leaders, business people, and others to speak out against the overwhelming post-9/11 call for revenge and military action. He didn’t hesitate for a second to join in.

Karen Dolan, Director of the IPS Criminalization of Race and Poverty Project

Harry Belafonte with Karen Dolan

In the late 1990s through the early 2000s, Harry Belafonte, along with his civil rights compadre Danny Glover, joined IPS’s Economic Human Rights Bus Tours. We traveled with advocates and Congressional Progressive Caucus members to places in the nation left out of the economic boom of the ’90s and before.

Harry, or “Mr. B” as he liked being called, was integral to these trips. Because of his and Danny’s storied civil rights activism and their public celebrity, their presence on these often grueling and definitely “no-frills” trips brought the media to places they otherwise wouldn’t go.

Harry helped us shine a light on the demands of Black farmers in Georgia, long left out of U.S. agriculture policy and neglected by centuries of racist public policy. Harry and Danny went with us to union halls, schools, and soup kitchens in the South and Midwest. They accompanied us into the desolation of rural poverty in Appalachia and to the inequities and shameful disinvestment of Detroit neighborhoods.

Through all of this, Harry and Danny stood as a beacon for those whom they visited, immediately recognized, and respected. Their civil and human rights records for justice and dismantling systems of racism and other oppressions gave our movement the credibility we needed to bring visibility to the invisible, and voice to the voiceless. They made policy-makers stand to attention, listen, and act.

Though his relationship with IPS — especially through Saul Landau and former IPS board chair James Early — preceded this work, the bus tours brought Harry closer to IPS and our movements. Soon after, he joined our board to further help our mission to speak truth to power and end systemic oppression. We are so very grateful for his presence, support, and work with us. He was greatly loved and is greatly missed.

Sanho Tree, Director of the IPS Drug Policy Project

Harry Belafonte and Sanho Tree in Georgia, circa 1998, on trip to help the National Black Farmers Association.

I first met Harry through my friend and IPS mentor Saul Landau in the mid-1990s when we shared a taxi together after an event at the newly renovated Lincoln Theater in DC. About a year later Harry asked us if we would help him in preparing his memoirs. That led to more than a year of interviews about his early life, reflections on world events, and his relationships with some of the most famous figures of the 20th Century.

It was through those dozens of hours of conversations that I learned about his childhood in Harlem and Jamaica, his enrollment in the segregated Navy in World War II, and his early forays into the struggles for social and racial justice that would come to define the rest of his life.

While in the Navy, the older sailors would throw books at him to read to keep the young Belafonte out of their hair. That was when he was introduced to the writings of W.E.B. Du Bois — a giant he would later come to know. It’s remarkable to think that Harry’s life was a living link to a legendary figure born in 1868.

One of the most memorable times I had with Harry was spending a week in Cuba with him and Saul Landau. We went to interview Fidel about Cuba’s intervention in Angola which ultimately led to the humiliating defeat of South African forces at the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale in 1988 and contributed significantly to the downfall of the Apartheid government. That trip also resulted in Harry, an accomplished amateur photographer, taking the most extraordinary and treasured photograph of my life.

When I began working in drug policy reform at IPS in 1998, Harry was always there to lend his name and his support. When I broached the subject of his joining the IPS board, he couldn’t have been more enthusiastic. A formal invitation followed shortly afterward. He became a convener, connector, and conscience for us and for so many other social movements as well.

Harry’s lifelong commitment to social justice brought us together with many wonderful groups both domestically and abroad. One of those fantastic groups was Barrios Unidos which had done tremendous work on gang truces, violence prevention, and community development. They became a recipient of our Letelier-Moffitt Human Rights Award in 2005.

Throughout his decades of involvement with IPS, Harry never hesitated to lend help in opening doors, making connections, and speaking out for justice. He not only blazed his own remarkable trail through history, but he also used his life to connect the forces of good.

Phyllis Bennis, Director of the IPS New Internationalism Project

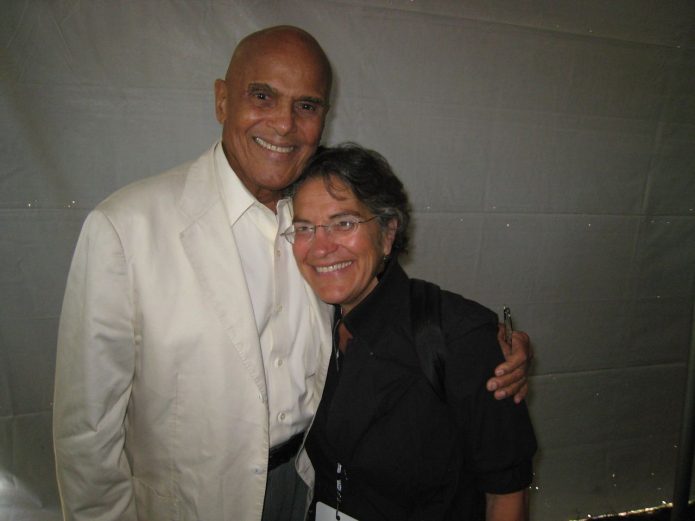

Harry Belafonte and Phyllis Bennis as a labor and civil rights rally in 2010. (Photo by Pam Belafonte)

Harry Belafonte was one of the greats of a generation of extraordinary heroes and artists, organizers, and agitators. His commitment to civil rights, to fighting racism and supporting workers rights, was legendary. He was known around the world for his solidarity with Africa, his support for decolonization, and his work as a global ambassador for UNICEF. He was a giant of internationalism.

Across the United States, people long familiar with Harry’s work in film, theater, and music, as well as his resistance to racism and his deep ties to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the civil rights movement, still heard only pieces of what Harry’s commitment to internationalism looked like.

Harry’s powerful engagement with President Nelson Mandela and the struggle against South African apartheid was celebrated around the world, especially in the Black community of the United States. But other, quieter campaigns went forward with far less public attention.

In the mid-1960s, Harry arranged for a dozen young activists from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, SNCC, to travel to Guinea to meet Sekou Touré, recently inaugurated as the first president of the newly independent country. The young civil rights activists had spent years as field workers, registering Black voters in the Jim Crow south, and they were exhausted. They had faced beatings, jailings, the deaths of too many of their friends.

Harry recognized how important it would be for these young leaders to see firsthand an independent African nation ruled by a Black government. He was right — and it changed their lives.

Working with Harry Belafonte was a gift — and every time I had the chance to meet with him, there was always something more to learn. Things like how to balance principle and strategy, and how to bring international solidarity to mobilizations for labor and civil rights.

In 2010 a huge DC rally brought together the main organizations linking those two struggles. It was just over a year into Obama’s first term, and the president was already moving to dramatically escalate the war in Afghanistan. The rally leadership was reluctant to criticize Obama and his war, so our efforts to add a speaker from the anti-war movement went nowhere.

But Harry Belafonte was the lead speaker at the rally. And at the last minute, he immediately agreed to a private request to include a few lines calling for peace instead of escalation. His call for peace resulted in a huge ovation that swept the crowd to their feet. Harry’s principles never wavered.

Harry’s memoir My Song is one of the best histories of the U.S. civil rights movement, told from his place inside the movement’s inner core but reflecting the vantage points of so many in its outer circles too.

Harry is irreplaceable. But being who he was, he leaves behind an extraordinary gift for all of us, for the movements and struggles he so loved: a new generation of activists and artists — people Harry mentored and befriended, taught and encouraged, and bailed out of jail — who will continue to carry on his song.