This week, the Giving USA Foundation published Giving USA 2022: The Annual Report on Philanthropy for the Year 2021, the gold-standard report on charitable giving in the United States. 2021 was a difficult year of global pandemic, political turmoil, and soaring inflation, and Giving USA tells an inspiring story about the resiliency of philanthropic support in the face of these challenges. But this story glosses over two important pieces of long-term context: what has happened to the giving capacity of typical Americans, and where much of the charitable giving has actually gone.

According to Giving USA, the total amount given to charity in 2021 was nearly $485 billion, with giving by individuals making up $327 billion of that total. This individual giving was an increase of 4.9 percent from the previous year in current dollars, or 0.2 percent when adjusted for inflation.

Some of the flatness in individual giving can certainly be explained as a return to more normal levels after a pandemic-related surge in 2020. There was a large spike in giving during the first pandemic year, and it is remarkable, on the surface of it, that giving stayed at roughly the same level in 2021.

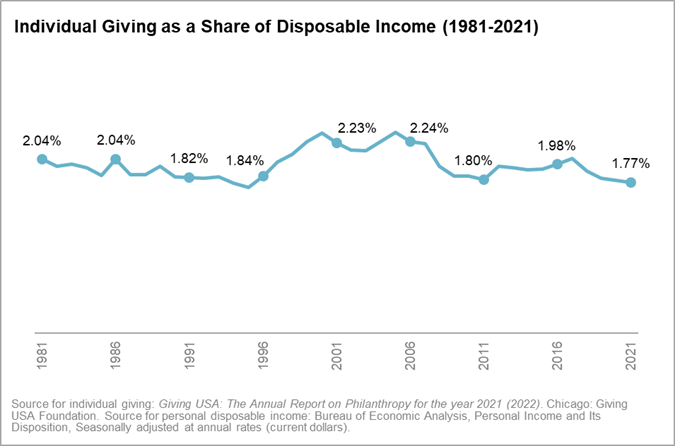

But in order to really evaluate Americans’ charitable giving, we have to look beyond raw giving dollars. One of the most helpful metrics to use is individual giving as a percentage of disposable personal income, since it measures how much money people felt comfortable giving away to charity after paying taxes in any given year.

Individual giving as a percentage of disposable income has been remarkably consistent over the past forty years, rarely straying from a narrow range between 1.8 and 2.2 percent. But it has generally been in decline for the past five years, and, according to the new numbers in Giving USA, it fell to just 1.77 percent in 2021. The last time it was lower than that was in 1995, when the U.S. economy was still feeling the effects of the 1990-1991 recession.

In other words, the average American gave a smaller chunk of their disposable income to charity in 2021 than they had in the previous twenty-six years.

And a deeper, more important story underlies this trend, which is that charitable giving has been growing more and more top-heavy for decades. As charities receive shrinking amounts of revenue from donors at lower- and middle-income levels, they are relying more on larger donations from smaller numbers of wealthy donors. And that spells trouble —not only for charities, but for our society generally.

Individual giving has been declining steadily as a percent of total charitable giving in the United States for the past 30 years, paralleling the decline in relative wealth of typical Americans over that time. According to Giving USA, individual giving accounted for 80 percent of all charitable giving in 1991. But by 2021, thirty years later, donations from individuals had fallen to just 67 percent of all charitable revenue.

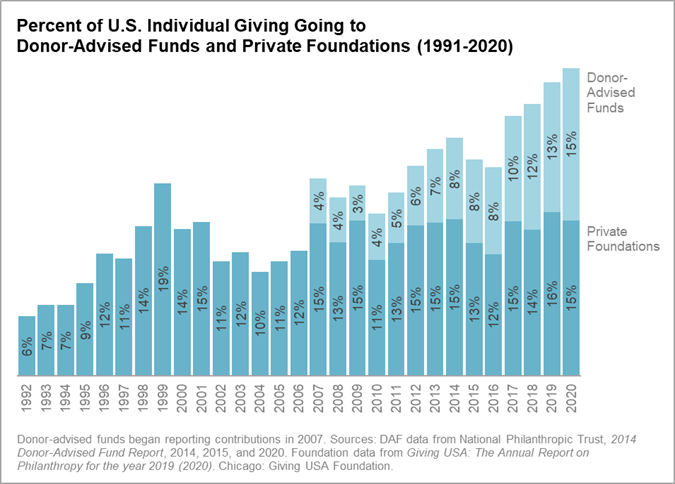

This makes sense. As economic times get tougher for ordinary Americans, they can’t afford to give as much of their spending money to charity, leaving nonprofits to look to deeper pockets to make up the difference. As a result, private foundations, corporations, and major donors are making up an increasingly larger share of U.S. giving each year. According to Giving USA, for example, as the share of giving from individuals declined, the share of giving coming from foundations rocketed up, rising from 8 percent in 1991 to 19 percent in 2021.

Mega-philanthropists have similarly been intensifying their influence over the nonprofit sector with record-breaking donations. The world’s richest men — Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, and Bill Gates — have all made multi-billion-dollar contributions in the past couple years, reducing their taxes by millions of dollars with charitable tax breaks. Mega-giving was so lavish, in fact, that Giving USA’s threshold for what qualified as a mega-gift jumped to $450 million in 2021, up from $350 million just the previous year.

And the important thing to know is that when wealthy people give, they tend to give not to independent charities, but to intermediary giving vehicles that they control. This includes, in particular, private foundations and donor-advised funds, or DAFs. As giving becomes more top-heavy, an ever greater share of U.S. charitable dollars is pouring into these intermediaries. A full 30 percent of individual giving is now being diverted into foundations and DAFs—up from just 5 percent thirty years ago.

According to tax and philanthropy experts James Andreoni and Ray Madoff, this has resulted in a shortfall of $300 billion to active charities over just the past five years.

As an intermediary-giving case in point, Elon Musk gave a staggering $5.7 billion donation to charity in 2021 — the largest mega-gift reported in the Giving USA report. But Musk’s gift was only exposed through a mandatory SEC filing, and the recipient was only listed as “undisclosed,” leading many experts to think that it likely went into a donor-advised fund. If this is true, it may very well be the largest single gift given to a DAF to date.

The relentless declines in relative individual giving and the growth of charitable intermediaries are a double whammy for America’s operating nonprofits. And the shift toward top-heavy philanthropy means that even when charitable giving is stable or growing, less of it actually makes its way to working charities serving the public. We are also still in a pandemic, we’re still experiencing massive inflation, and a recession likely looms on the horizon. None of these things bode well for giving in 2022 and beyond — and they should concern all of us who care about the health of our nonprofit sector.