Within an hour on that day in July 1975 I was fired from my Senate job, Kitty called excitedly to tell me she’d been accepted by the Antioch School of Law. With her usual unflappable demeanor, she took my bad news in stride, and said another door will open for us.

With two kids and now my wife about to go to law school, I put in a call to Joe Browder, director of the Environmental Policy Center (EPC), whom I had been working with on Western coal issues. Joe immediately told me I was hired and that he just received a grant that would cover a salary of $14,000 a year plus health insurance.

In September 1975, I started my new job with EPC to work on nuclear power issues. This came as a surprise, as the work that attracted Joe to hire me was based on my efforts to protect water supplies in the arid west from large-scale coal development. More than 40 years later, conflict over water in the West between Indian tribes, farmers, ranchers and the energy industry have only intensified.

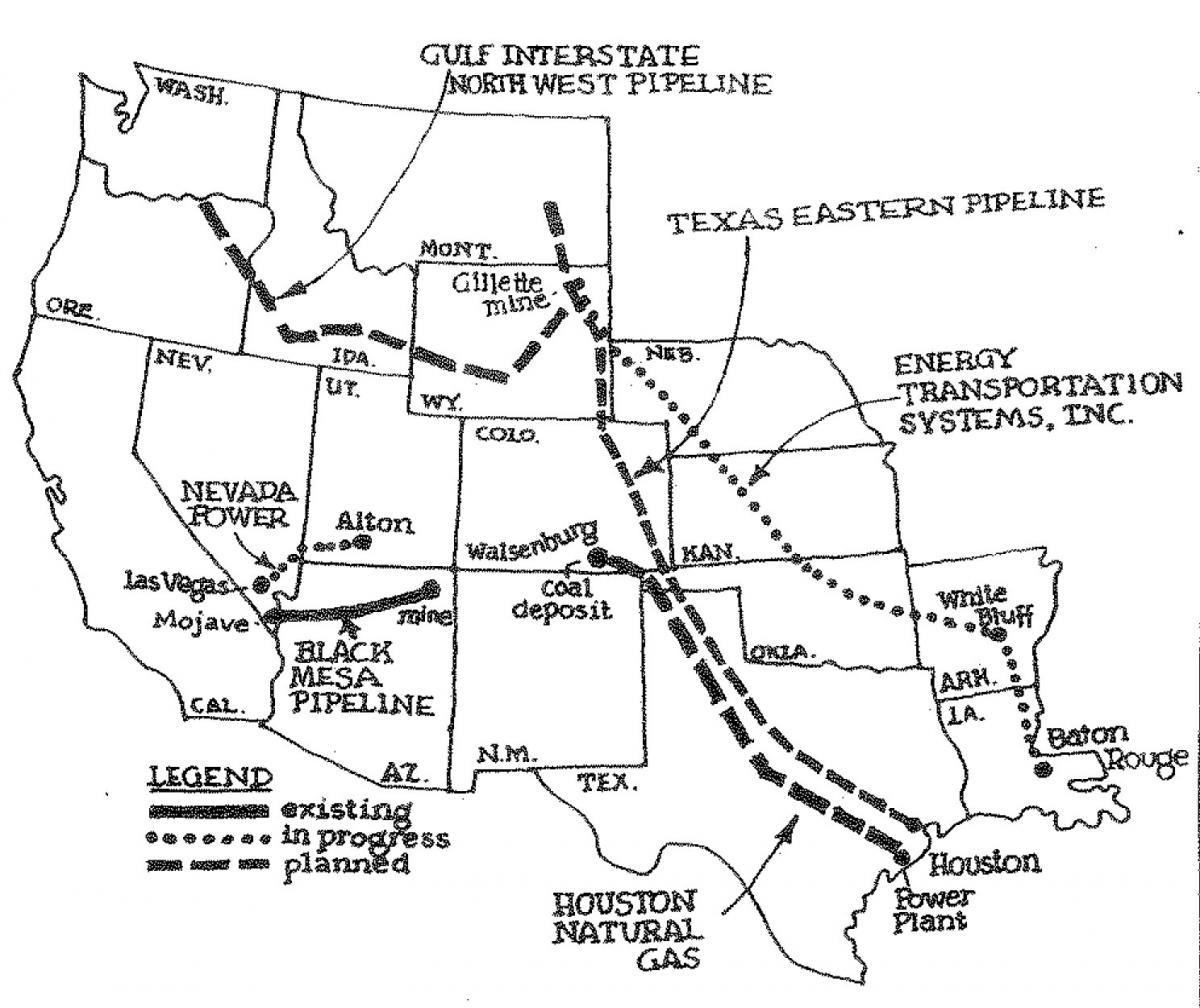

At the time, I was involved in efforts against the major push by the Nixon Administration and members of Congress to greatly expand the coal fields in the West in response to the 1973 oil embargo. I became quite active in opposing a coal slurry pipeline that would span 1,800 miles from the Powder River Basin in Wyoming to electrical power plants in Arkansas, Louisiana, and Oklahoma.

In the summer of 1974, my boss, U.S. Senator Abourezk (D-SD), had dispatched me out to Rapid City, South Dakota with the advice of “go get ‘em, Bob.” Kitty, who was pregnant with our daughter Amber, our son Shaun, and I all piled into our 1962 Ford station wagon. Jim Abourezk kindly helped pay for a necessary engine overhaul to get us to Rapid City.

Before I left, I was warned about the coal slurry project by John McCormick and Brent Blackwelder from the EPC, who showed me data that it could impact the water supplies for South Dakota ranchers. That part of the semi-arid state usually received 10-14 inches of rain per year.

As we drove it became clear once we crossed the Missouri River that South Dakota had two very distinct geographic areas with separate time zones. The “East River” area received more rain and had a rolling terrain. The areas near the Minnesota border had fertile rich back soil and glacial lakes, similar to the area where Kitty grew up amidst dairy farms in northern Wisconsin.

The “West River” area was like entering a different planet of endless steppe grassland known as the Northern Great Plains.

Once the floor of a shallow inland sea millions of years ago, it is now in a vast, semi-arid, seemingly empty expanse interrupted by ravines. For a city boy like me, I was oblivious to the array of creatures inhabiting this area where there was no respite from an all-encompassing sky. After hours of driving, the mountainous and verdant “Black Hills” were a startling sight which suddenly appeared with their evergreen forests.

With the help of the Senator’s staff in Rapid City, we quickly found a small furnished house — a 30-minute walk to the office.

At the advice of Brent and John, I established contacts with environmental activists who were organizing farmers and ranchers in the face of massive coal strip mining about to commence in the region. However, there was little happening in South Dakota, mainly because it wasn’t rich in coal reserves. But there were enormous coal reserves in Wyoming along the Powder River Basin. The plan to dig up millions of tons of that coal and mix it with ground water next to the South Dakota Black Hills had not yet registered on people’s radar screens — something I was determined to change.

The environmental activists in the Northern Great Plains embodied a generational change, which challenged the pro-energy and water development visions that came out of the New Deal. The northern Midwest was among the last areas of the country that received electricity from construction of dams and the formation of rural public power electric cooperatives. Public power created by major hydroelectric dams on the upper Missouri River was the culmination of a decades-long populist battle waged by farmers and ranchers, who were often under the thumb of ruthless banks, railroads, and energy and agricultural corporations in Chicago and Minneapolis-St. Paul.

The new Deal helped change things by adopting much of what the populists of Northern Great Plains had fought for. A few remnants are still around, such as the state-owned Bank of North Dakota. But over the years, especially after World War II and through the 1960s, the belief in unfettered growth became an article of faith.

Now the rural electric cooperatives had united into a powerful political force in the region and jumped on the “energy independence” bandwagon, supporting large-scale strip mining and coal burning power plants dotting the landscape. An activist from North Dakota would refer to his parents as the “all electric kitchen” generation, who believed in the motto of “bigger, faster, forever.”

Within a week of arriving in Rapid City, I embarked on a report under the auspices of Senator Abourezk’s office about the groundwater impacts of the coal slurry pipeline project. It pointed out that coal slurry pipelines require about one ton of water, or 250 gallons, to move one ton of coal.

One coal slurry pipeline could consume as much water per year as a town of about 65,000 people. Three coal slurry pipelines would exceed the “replacement flow” that replenishes the major three-state aquifer supplying water for municipalities, farmers, and ranchers in the Northern Plains. The U.S. Geological Service pointed out in one of its technical reports that “large-scale development … could impact the ‘plumbing system’ in the Black Hills area that controls interactions between ground-water levels and artesian spring-flow.”

Very soon an article about the report ran on the front page of the Rapid City Journal. This was followed by a public forum I organized on behalf of Senator Abourezk at a high-school gymnasium in the small town of Edgemont, right on the border with Wyoming.

Unlike in the friendly offices of the Wyoming state legislature, representatives of pipeline company, Energy Transportation Systems, Inc. (ETSI), quickly proved to be out of their element. The ETSI representative was from New York City and wore a dark three-piece pin-stripe suit. The event started off with a young rancher, who mentioned that he and his family were just starting out and had a spread a few miles away from the proposed groundwater pumping operation. When he was asked if the project would impact the water, the ETSI official deferred to his expert, a fast-talking professional hydro-geologist from Boise, Idaho. He wore a bolo tie cinched with a large piece of turquoise, a soft, buckskin sport coat, blue jeans, and custom-made, alligator-skin cowboy boots.

After being told that there was more than enough water for everybody, the rancher suddenly lunged from the gym bleachers and had to be restrained. ETSI’s water expert promptly exited the gym and the meeting ended abruptly.

In the chaotic aftermath, which drew even more media attention, Senator Abourezk remained aloof, even after I was called on the carpet by State Democratic Party officials and staff in the governor’s office. It appeared they were being wooed by ETSI for help in the 1974 elections. After more than a decade of promotion, however, the coal slurry pipeline project was dropped, never recovering from its collision over water rights.

As for me, I went on to deal with America’s romance with the atom.