Shutterstock

A society with high levels of inequality of incomes and wealth inevitably leads to high levels of inequality of living standards. One such dimension of inequality in the United States today that does not get the attention it deserves is the incidence of energy insecurity.

Low-income households pay a much higher share of their income in utility bills compared to the average of all U.S. households, as reported by the Department of Health and Human Services.

But these numbers are just averages — many low-income households pay a much greater portion of their earnings just to keep their lights and heat on. A 2016 study of U.S. cities found that the median share of household income spent on utilities exceeded 10 percent in three cities. The lower limit of the highest quartile of household energy burden exceeded 15 percent in nine cities, skyrocketing as high as 25.5 percent in Memphis, Tenn.

When households with limited means find their utility bills consume such large portions of their income, they’re often faced with hard choices. Almost a third of the U.S. population has experienced one or more of the following:

- Having to choose between paying for utilities and paying for food, doctor’s appointments, or medications.

- Having their utilities disconnected because of missed payments.

- Setting their thermostat at an uncomfortable – or potentially even dangerous — temperature to save on energy bills.

- Heating their homes with wood stoves to cut their energy bills, in spite of the elevated risk of fire and exposure to toxic carbon monoxide gas.

The numbers are even more drastic for people of color and low-income people. The percentage of Native Americans facing energy insecurity is double that of the general population, and more than half of Black households experience the same.

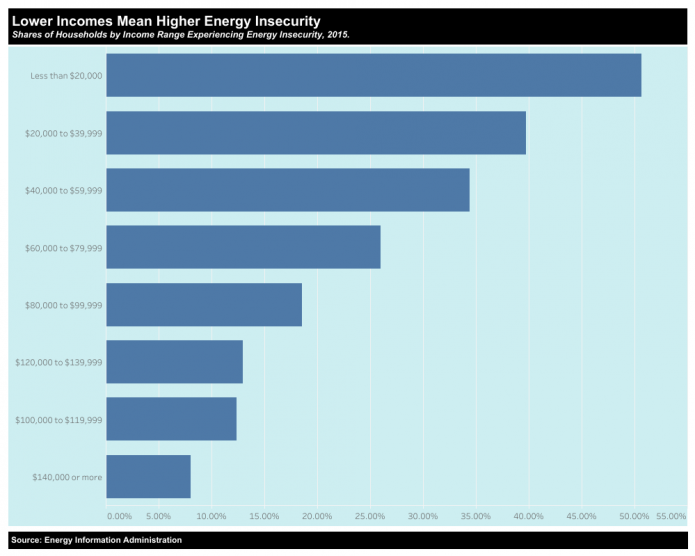

Unsurprisingly, energy insecurity also drastically increases as household income decreases.

These numbers have real-life consequences, several of which were outlined in an NAACP report last year. Take, for example, the needless death of an elderly patient of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and congestive heart failure in Texas. His family had notified the utility company that he would die without electricity for his oxygen concentrator. But that didn’t stop the utility from shutting off his power over just $129.62 in unpaid bills. He died from suffocation.

A radical redistribution of income and wealth — along with dismantling the systemic racism that keeps people of color trapped in poverty — would of course address these inequalities. But we also have tools to deal with the crisis of energy insecurity more immediately.

Energy efficiency policies designed with the twin goals of reducing pollutants and addressing energy insecurity can drastically lower utility bills for low-income households. Even better, these policies are largely in the domain of states and, to some extent, cities. This means they’re not vulnerable to the whims of our current fossil-fuel crazed federal government, and they don’t have to be put on hold until a new administration takes office.

In an Institute for Policy Studies report, I outline key elements of an energy efficiency policy centering racial and economic equity. The options are too numerous to detail exhaustively, but here are a few of the most important:

- Dedicated funding for low-income energy efficiency, drawing from some combination of mandates for utilities and direct state funding.

- Disconnection assistance for low-income customers.

- Language access to ensure that households in which adults speak little to no English, and communities with a large share of such households, are not left out of the benefits of energy efficiency.

- Making energy efficiency program information widely available using print, radio, TV, in-person door-to-door outreach, etc. instead of relying solely on online outreach, given the persistence of the digital divide.

- Address renters’ needs. 37 percent of U.S. households are renters, and the numbers are much higher for households with annual income below $20,000 (59 percent), Black households (58 percent), Native Hawai’ian and Pacific Islander households (56 percent), Latinx households (55 percent), and Native American households (52 percent). Bill-neutral financing for energy efficiency upgrades tied to utility meters instead of properties can address renters’ needs, especially when paired with targeted incentives for low-income rental housing owners to make their buildings more energy efficient.

More good news: many of these policy elements are already being implemented in a number of states, including Illinois, Maine, Massachusetts, New York, Oregon, and Wisconsin. By strengthening these policies where they exist and enacting them where they don’t, we can make a real difference to tens of millions of energy-insecure households.