As the U.S. military wreaks havoc in faraway places around the world, a new book by Winona LaDuke and Sean Cruz sheds light on the historical and continuing damage done to native peoples and their lands within the United States and its colonial holdings.

As the U.S. military wreaks havoc in faraway places around the world, a new book by Winona LaDuke and Sean Cruz sheds light on the historical and continuing damage done to native peoples and their lands within the United States and its colonial holdings.

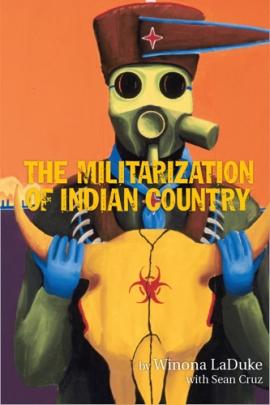

Author, activist, and two-time Green Party vice-presidential candidate (1996 and 2000) Winona LaDuke is an Anishinaabeg national, and her latest book, The Militarization of Indian Country, marks her fifth work on this subject. Only 70 pages, this short book surveys a wide range of issues related to military incursions into Native America without delving too deeply into any of them. But at the book’s end the reader will find a number of resources both online and in print to flesh out the issues raised.

Beginning with a description of the Ogichidaa – the Ojibwe title of the Indian warrior – the first part of the book deals with the contrasting perspectives on the conflict between Native Americans and U.S. armed forces. LaDuke quotes the legendary anti-colonialist Lakota Chief Sitting Bull who said, “The warrior is not someone who fights, because no one has the right to take another’s life. The warrior, for us, is one who sacrifices himself for others.” Whereas ”the greatest honor a warrior could achieve was…touching his enemy without inflicting any bodily harm,” the U.S. military has always wielded its power through pure force, inflicting maximal damage to acquire whatever the state desires.

From this point of departure, LaDuke goes on to detail Native participation in the U.S. military. Native peoples have a higher per capita rate of participation in the armed forces than any other ethnic group. Indeed, conscription of Native men was a major motivation for the U.S. government to grant citizenship to Native people in 1924, as participation in the First World War generated a patriotic frenzy and calls for universal conscription. However, citizenship did not imply legal rights or the right to vote, which many states withheld from Native people until the 1950s.

LaDuke shows how the military’s exploitation of Native communities has contributed to the depression of reservation economies throughout the country. An allegedly pro-Native law allows for contractors with tribal connections to win no-bid contracts with the military, but loopholes within the law (largely the legacy of former Alaska Senator Ted Stevens) allow for major corporations to simply bribe their way to native status, as was the case with the mercenary giant Blackwater (now Xe Services). Blackwater secured preferential contracts by subcontracting to Alaskan contractor Chenega Native Corporation, which in turn received a cut of the massive profits.

Perhaps the richest and most disturbing section of the book deals with the military’s use and abuse of Native peoples’ lands. Many of the reservations on which the government forced Native Americans to live began as military installations; hence several are named “Fort X” after various “heroes” of U.S. conquest. In the 19th century, these forts began as protective settlements where soldiers and westward pioneers lived while launching military operations against the surrounding Native communities. After slaughter, systematic starvation, and forced assimilation destroyed the communities, the forts focused on “educating” the survivors out of their traditional ways of life.

After establishing the reservation system, the U.S. government systematically abrogated tribal treaties, and the laws to this day allow for the appropriation of any lands deemed essential for “national security.” The Pentagon has thus claimed hundreds of thousands of acres of ancestral native lands. The remaining lands occupied by native peoples tend to be located near military sites that test chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons. Indeed, “if the Great Sioux Nation were in control of its 1851 treaty area,” writes LaDuke, “it would be the third greatest nuclear weapons power on the face of the earth.” Native peoples have thus been unwittingly transformed into test subjects, and native lands have been turned into contaminated wastelands.

But the book ends on a positive note, detailing some of the successes in the long struggle against militarization and its harmful side effects. It might take centuries or even millennia to undo the damage that’s been done, and in some cases the losses are never to be recovered. But communities now have information they can use to empower themselves and fight against these historic injustices.