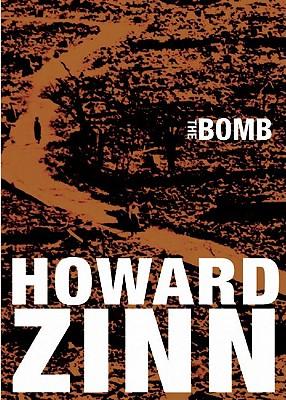

Howard Zinn died recently at the age of 87. His last book, The Bomb, is about his experience as a bombardier in World War II, and about the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It is also the story of his hatred of war and of how he came to confront its stupidity and criminality throughout his life, in the South fighting for civil rights and wherever justice was denied.

Howard Zinn died recently at the age of 87. His last book, The Bomb, is about his experience as a bombardier in World War II, and about the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It is also the story of his hatred of war and of how he came to confront its stupidity and criminality throughout his life, in the South fighting for civil rights and wherever justice was denied.

Zinn’s story is also my brother’s story. Like Zinn, my brother was a bombardier entrusted with the secret Norden bombsight that increased the bomber’s accuracy and the subsequent devastation of the targets. For Captain Melvin B. Raskin these were moments of release, a time when sex and destruction were intermingled, when the American national anthem stirred the blood in our veins, when mothers gave up their sons out of patriotism. My mother tried to hide my brother’s report to duty from President Roosevelt. But Mel Raskin reported anyway. He flew 29 missions, even though bombardiers, like World War II pilots, were only to fly 25 missions, collect their medals and have 30 days of rest before moving on to the next stage of war.

In Europe, as the war was winding down, the number of bombs increased on targets of opportunity. As Zinn learned, napalm was introduced in the April 1945 bombing of Royan, a seaside town, on the grounds of military necessity. It was the same military necessity argument that left 135,000 dead in Hiroshima and Dresden. Allied bomber pilots and officers incinerated Nazis, Japanese soldiers, women, and children alike. Law and international law is formulated and applied by the victors. How else to explain Churchill, Roosevelt, and others escaping the justice applied at Nuremberg?

But most Americans breathed a sigh of relief with the dropping of the uranium bomb. Gandhi opined that when the United States dropped the atomic bomb on Japan that the United States had lost its soul, but Harry Truman quacked that the Japanese had better surrender unconditionally lest they be the recipient of more nuclear weapons. The Japanese, of course, had already sought to surrender through emissaries. But the United States insisted instead on unconditional surrender, a concept used by Lincoln and Grant during the Civil War.

Zinn, the people’s historian, leaves us with words that bring together thought, action, and passion. His experience during World War II left him unpersuaded by the arguments of military necessity and the appeals to nationalism. We must refuse “to be transfixed by the actions of other people, the truths of other times,” he writes in The Bomb. This “means acting on what we feel and think, here, now, for human flesh and sense, against the abstractions of duty and obedience.”