This week we remember Bill Gates Sr., the father of the founder of Microsoft. I had a unique friendship with the man, meeting up later in his life out of our shared passion for preserving the estate tax as a brake on the corrosive concentration of wealth and power.

Bill was a gentle and humble soul. He was one of those people who saw the web of human interconnection. His views about progressive taxation flowed from this knowledge. He never forgot that he received the GI bill that enabled him to attend the University of Washington for both undergraduate studies and law school.

He believed that a good society should invest in people. And if you accumulated great wealth you had an obligation to pay back society so that others could have the same opportunities. The estate tax, in his view, was an economic opportunity recycling program.

I remember getting a call from Bill in early 2001. President George W. Bush had campaigned on the “end the death tax” platform. He threw himself completely into the fight to defend the estate tax. In early 2003, we traveled to 15 cities to promote our book, Wealth and Our Commonwealth: Why America Should Tax Accumulated Fortunes.

I remember getting a call from Bill in early 2001. President George W. Bush had campaigned on the “end the death tax” platform. He threw himself completely into the fight to defend the estate tax. In early 2003, we traveled to 15 cities to promote our book, Wealth and Our Commonwealth: Why America Should Tax Accumulated Fortunes.

What follows are a couple of stories that I believe capture Bill’s generous spirit (There are more in Born on Third Base).

May the light perpetual shine upon him.

***

On the Road with Bill Gates Sr.

“Bill,” I say. “You really should wear a hat.”

“No thanks,” he says, looking out the side window of our rented Blazer at three-foot snowdrifts. It is a frigid February morning in Portland. There is an inch of fresh snow and more on the way. Bill Gates Sr. and I are driving to a breakfast program.

“It’s like 15 degrees below zero with the wind chill,” I needle. “Let’s stop and get you a nice wool cap?” After being on the road for several weeks, I still feel responsible if the big guy gets sick.

“No thanks,” he says stubbornly. “It’s not that cold.”

We pull up to a hotel where 250 small-business owners crowd into a sold-out morning breakfast discussion of the estate tax. Bill and I are the featured speakers.

“Oh boy,” Bill says as he bounds out of the car onto a sheet of ice. “This is gonna be fun.”

***

During the first two months of 2003, I traveled with Bill Gates Sr., promoting our book, Wealth and Our Commonwealth: Why America Should Tax Accumulated Fortunes. With George W. Bush in the White House and Congress in GOP hands, there was another push to abolish the estate tax. Gates and I did press conferences, interviews, talk shows and lectures in major cities, attracting audiences of 600 and 700 people on some evenings. We recruited thousands of people for our campaign to preserve the estate tax.

Our first stop was Washington D.C. where several Senators co-hosted a private luncheon for George Soros, Bill and me with 15 U.S. Senators in the Capitol. After we made our case for preserving the estate tax, Senator Ted Kennedy’s hand was the first to shoot up with a comment.

“Well, I agree,” said the late senator from Massachusetts. “I agree with all these points you make. That it would be fiscally irresponsible to cut the tax. And it would be a terrible blow to charitable giving. But I don’t really understand your last point,” the Senator beamed impishly. “What do you mean about the dangers of hereditary wealth and power?” All the Senators roared with laughter.

Bill—a retired attorney whose son at the time was the world’s wealthiest person —is great with people. All along our tour, he listened patiently to all kinds of questions –and graciously fended off two dozen grant requests a night. “I am not here on foundation business,” then co-chair of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation would carefully explain. He gave out stacks of his business card, with his own personal email.

***

In Portland, I give the warm-up talk at our business breakfast. In the previous three weeks, I have given this talk twenty times, explaining the myths surrounding the estate tax, the costs, and the political context. My role is to enlist people who come to our events to join our campaign. But this morning is different. Many of the people in the audience are business owners with GOP lapel pins, and they are probably happy to see the estate tax get axed.

When it is Bill’s turn to talk, he starts with a story. “A name like mine can get you into trouble,” Bill says, squinting at the audience. “My daughter Libby went into a ski store to buy a set of skis for herself and her two children. When she went to pay with a credit card, the guy in the store saw her middle name was Gates. ‘Are you related to him?’ the ski salesman asked. Libby was in no mood to discuss her famous brother. ‘No,’ she said. ‘I didn’t think so,’ said the salesman. ‘You’d have bought better skis.’”

The room bursts into guffaws, and Bill chuckles with them. Then he looks down at his notes, shakes his head, and looks up at them with a grimly serious face.

“Many of you probably want to get rid of the estate tax –or what you might call the death tax,” he says, and the room is silent. A few people shift in their seats and put down their coffee cups. “But before we lead it to the gallows, I’d like to make one more case for clemency.”

I have a prime seat next to Bill, and I study the audience and the expressions on people’s faces. The listeners are evenly split between men and women, most dressed in business suits and dresses. Their eyes are riveted on the father of Microsoft’s founder.

“Why should someone who has $10 million, $50 million, or $50 billion pay an estate tax?” he asks and then smiles broadly. “Actually, I know only one person with $50 billion.” The audience titters again, with this reference to his successful son.

“If you have accumulated tens of millions, hundreds of millions or billions, you did not do it alone. You got help.”

“Of course, this is not to take away anything from that person. Those of you in business know what it takes. These are probably hard-working and creative people who have made sacrifices. They deserve some reward for their leadership or entrepreneurship. But they didn’t get there alone.

“Where would they be without this fantastic economic system that we have built together? Where would they be without public investments in infrastructure? Roads? Communication? Our system of property rights — and the legal system to enforce them. How much wealth would they have without the public investment in new technology? These advances have made us all more prosperous, whether we are software designers, restaurant owners, or neighborhood realtors.”

“Who is the greatest venture capitalist in the world today?” Bill stops and repeats his question. He rocks back on his shoes and looks at the audience over the rim of his glasses. They are rapt.

“No, he’s not one of those angel investors who live on Sand Hill Road down from Stanford University. The greatest venture capitalist is Uncle Sam.” He repeats: “Uncle Sam.”

“Has your business become more productive thanks to these public investments? You bet it has.” Bill describes the early government investments in technology that led to the creation of the internet and World Wide Web. He talks about jet engines, publicly funded university research and the human genome.

“Where would we be without the fertile ground we have plowed together? Would we be as wealthy and successful if we had to toil in different soil?” Outside the window, the sky is darkening, and the snowfall is intensifying, but no one is slipping away to avoid driving at the height of the storm.

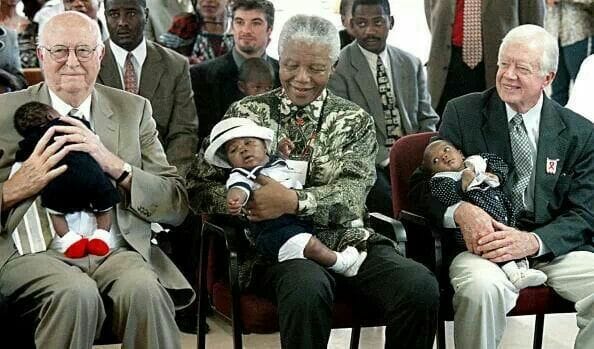

“I recently was in Nigeria. Jimmy Carter and I met with African leaders seeking an end to the AIDS crisis.” He describes his recent trip. Most people in attendance have probably seen the widely published newspaper photographs of Bill cradling an infant sitting next to Nelson Mandela and former President Carter.

“I was deeply impressed by the spirit and resourcefulness of the people I met. But the infrastructure and conditions for business are quite different in Abuja than here in Portland, Maine. Take your sweat and talents and try and grow a business in Abuja or Kinshasa. Many years later, you will still be toiling with little to show.”

“Most of us benefit from society’s investments. And those who have accumulated $10 million or $10 billion have disproportionately benefited from them. I believe it is fair to have an estate tax that captures a third of that wealth when it transfers to the next generation. It is a reasonable levy for the privilege of growing such wealth in our society.”

I have heard Bill speak some of these words before, but today he seems to be drawing on a deeper well. His hand trembles slightly as he takes a drink of water.

“The estate tax is an appropriate mechanism for a wealthy person to pay back society, a means of expressing gratitude for the amazing opportunities that we have. Gratitude –there’s a word largely absent from our business publications. We live in a marvelous system with abundant commonwealth –yet we don’t see it around us. We inherit some of it from those who came before us.”

I look across the audience. People’s faces have softened. Several women are silently weeping, and a few men dab tears from their eyes. What is going on here?

“A woman came up to me after a talk in California,” Bill shifts his voice into a conversational tone. “She said ‘Mr. Gates, what I hear you saying is that we are all in the same boat.”

“Yes, we are all in the same boat. We won’t get very far if we leave people behind. No one achieves wealth alone. If you meet someone who tells you they are self-made, invite them to try and grow wealth while living on an island. Our wealth is only as good as the commonwealth and societal investments around us.”

“I’d like to close with a parable. I hope no one is offended by this image of our maker. Imagine that God is sitting in her office.”

Everyone laughs, and several of the women applaud and cheer.

“She is agitated, fretting really. It appears that the treasury of heaven has been depleted. It was probably overly invested in technology stocks.” More laughter.

“Suddenly she realizes a solution. She summons before her the next two beings about to be born on Earth. She explains to these two spirits that one of them will be born in the United States and the other will be born in an impoverished nation in the global south. Her scheme for raising revenue is to auction off the privilege of being born in the United States.”

People have eager smiles on their faces. Still, no one is concerned about the steady snowstorm that is burying their cars in the parking lot. They are Mainers, after all, confident in their municipal snowplows.

“Of course, God is not a nationalist, nor a believer in cultural superiority. But she recognizes that the United States has an advanced infrastructure of public health, stability, education and market mechanisms that enhance opportunity. She understands that some humans might consider it a privilege or advantage to be born in such a society. The spirits are instructed to write the percentage of their net worth they pledge to God’s treasury on the day they die. Whoever offers the highest percentage will have the good fortune to be born in the United States.”

Bill looks calmly at the audience. “Okay, I want you to write on a piece of paper the percentage of your net worth that you will yield on the day you die. What is it worth to you to do business in the United States?” He pauses to give people a moment to jot down a number.

“We’ll do a poll. How many of you wrote 25 percent?” He looks around, beaming with delight. “No one.”

“How about fifty percent?” Again, no hands in the air. “That’s more than an estate tax, which has an effective rate of 30 percent.”

“How about 75 percent?” Three hands shoot up. “Okay, we have a few takers.”

“And how about 100 percent!” Every remaining hand in the room goes up, with several bolted straight up like the confident kids in the class. More people wipe tears from their eyes and blow their noses.

“One hundred percent. What is it worth to you to do business is in this remarkable society? What is it worth to be an American?”

Bill sits down. There is a brief shocked pause, then people bolt up from their chairs with applause. Several listeners lunge forward to shake Bill’s hand or touch his arm.

I marvel at the emotional temperature in the room. What did Bill say that moved these people? Was it the spiritual truth of “we are all one body,” or “we are nothing without each other?” Was it a refreshing alternative to the “great achieving men of business” story that they usually hear? Was it Bill as the messenger?

Whatever it was, Bill had had touched something in these people, some universal truth of our interconnectedness. He had tapped into a basic sense of goodness and fair play. Perhaps for the first time, they had recognized the help that all of us receive.

***

“Bill, I had about twenty people come up to me and say they were Republicans and agree with us now.” We are back in the car, driving to a radio station. I have collected about fifty business cards –along with pledges to call the two Senators from Maine, two swing votes in our campaign to preserve the estate tax

“Yeah, we got some converts,” says Bill.

“Bill, your comments about ‘No one does it alone’ –I would keep doing that. All your examples about society’s investments were great.” If people could understand that concept, then you could have a sober conversation with them about taxes.

“That seemed to strike a chord,” he agrees. He looks straight ahead grinning and jingling the coins in his pants pocket. “Golly, this is the most fun I’ve had in years.”