Andrea Geyer/Sharon Hayes/Ashley Hunt/Katya Sander/David Thorne

9 scripts from a Nation at War, 2007

10 channel video Installation, HDV, color, sound

Investigating concepts such as national identity, gender, and class, German-born artist Andrea Geyer uses both fiction and documentary elements in her image and text-based works. Her multifaceted projects include Queen of the Artists’ Studios, The Story of Audrey Munson, an exploration of the continuous struggle of women through the life of one of New York’s most famous artist’s models. 9 Scripts from a Nation at War, her much-discussed collaboration with Sharon Hayes, Ashley Hunt, Katya Sander, and David Thorne, is a room-sized, 10-channel video installation. Through this complex presentation, the artists reflect on the war in Iraq and how it constructs specific positions for individuals to fill, enact, speak from, or resist.

Focusing on the ongoing readjustment of cultural meanings and social memories in current politics, Geyer has constituted a revolutionary as well as poetic body of work. Living and working in New York, she has exhibited at numerous prestigious institutions worldwide, including the Secession in Vienna, the Whitney Museum in New York, TATE Modern in London, and Documenta 12 in Kassel.

Niels Van Tomme: Your latest project, Solemnly Proclaimed, is a collaboration with a group of 10 Canadian Inuit activists around the UN Declaration for the Rights for Indigenous Peoples. What was the starting point for this project?

Andrea Geyer: I must say as a disclaimer to start off with that Solemnly Proclaimed is on hold right now, because there is absolutely no funding for it. The idea came out of two projects I’ve worked on since about 2003. 9 Scripts from a Nation at War deals with the situation of individuals in relation to the war that is happening in Iraq. The other project is Spiral Lands, a sequence of works that address land rights and questions of identity and identity claims in North America, taking the Southwest as an example.

![]()

Andrea Geyer, Spiral Lands / Chapter 2, 2008. Installation in an educational setting with slide projection, 80 color and black and white slides, voiceover 50 min, brochure with footnotes.

In both of these projects, the role of law and questions of justice became very prominent. Spiral Lands contains passages on how the court system was used to deconstruct Native sovereignty and land rights in the 19th century (see Cherokee Cases, Chief Justice John Marshall). And then, of course, there is the part in 9 Scripts From A Nation At War that addresses the detainees in Guantanamo Bay and the role of the Enemy Combatant Status Review Tribunals. Now, with the Obama administration, we’ll see how the detainees will be tried.

The project Solemnly Proclaimed looks at the Declaration for the Rights for Indigenous Peoples (DRIPS) that the UN passed in September 2007 After 30 years of trying to get it passed, activists finally built a consensus to ensure indigenous rights worldwide. The reason why there needs to be a special declaration is due to the history of colonialism and the fact that indigenous communities need a particular kind of protection, being colonized and living mostly within postcolonial conditions. There were four states that voted against DRIPS: Canada, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand (although Australia has signed it since). All were, interestingly enough, British settler states. They could not ratify the declaration, mostly because of questions of land rights and entitlement of Indigenous people to their land, their history, and their culture. Solemnly Proclaimed is the first part of a set of projects that I would like to develop if I can secure funding for them: working together with local indigenous communities in each of these countries. I’d like to engage with individuals and find out why this declaration is relevant, how this international law really ripples down into local communities. That was the starting point for me.

Van Tomme: This project is very much tied to an existing issue in society. In what way do you hope to engage differently with Indigenous people than, let’s say, activists or politicians can do in their work?

Geyer: As an artist I start my work outside certain preset expectations or rules of disciplines; the goals of the work can be multifaceted. When I went to Iqaluit, Nunavut (Canada), I didn’t know what I wanted, I wasn’t an activist going there with a particular goal in mind, I was actually trying to meet people to start a conversation. I wanted to know how we could work together to channel funds that were available within the realm of culture to do a project that engages the above-mentioned issues. In the beginning, it could be anything: two meetings in a meeting hall, a film screening, a documentary film, a theater play; there was no frame, it could engage two people or one hundred. Working this way, I can really build parameters or goals with the community itself and not come with a set of ideas that I apply on already existing structures.

I find that this is a huge problem with a lot of work that is done in all kinds of communities that are disenfranchised in one way or another. I feel that what I have to learn as somebody of privilege is to be quiet and listen to what’s really there, see how I can make my skills available for that community and get into a dialog. Solemnly Proclaimed as it is conceived at the moment is more or less a community project; there is no element of it that will become something that I will show as an individual artist. Perhaps there will develop something in collaboration with a few people in the group, but right now it doesn’t exist yet and it’s also not 100% given that it will ever exist, and I’m actually okay with that.

Van Tomme: So, the project is almost entirely community-based?

Geyer: It’s very community-based, which is something I learned from Spiral Lands, the project about land rights that I’m still working on, and my relationship to the people I met through it. When visiting the Southwest I was often asked: What are you doing here? What’s your stake? It took quite a while for me to be able to formulate that I was working with my experience of being a witness to the consequences of a past and unreconciled genocide, and colonialization and the continued disenfranchisement and theft of land, culture, and resources from the native communities. It is about my relationship as a resident of this country to the indigenous population whose land I’m living on. When I started Solemnly Proclaimed, I came with much more understanding of my interests and also of the need to actually find a full collaborator to work with on the project. That’s for me just a more interesting way to work; this is also why the third chapter of Spiral Lands is actually a collaboration with Simon J. Ortiz, a writer from Acoma Pueblo.

Van Tomme: As a European living in the United States, in which way do you think your perspective is different from American artists?

Geyer: I actually became aware of this through my collaboration with Simon. We met a couple of times, and then we traveled together and engaged in conversations about the history of this particular region in the Southwest and the history of my family. He is very interested in German history and currently works with the German writer Gabriella Schwab on a forthcoming book called Children of Fire, Children of Water: Memory and Trauma, about the way both memory and trauma travel across generations. Many of our conversations were circling around the specific history that I bring to the project, the kind of memory I carry with me as a German artist.

Andrea Geyer, Spiral Lands / Chapter 2, 2008. Installation Gasworks, London, May 2009.

Even though I have lived here for 14 years now, why am I sensitized to this particular subject? Of course it has to do with the very particular history of the country I was born into. Our conversations made me start working through things that were unconsciously very present in my understanding of myself but have never before been articulated in my work. I started to give lectures about how there are two kinds of memories that you have as a person when you have grown up in Germany in the 1970s, they are not yours but nevertheless they become yours. How living outside of Germany has activated them in a different way for me. How this memory that I carry in myself through transference, through my parents and through my education in school, conditions my action in the present moment. It made me understand more about my interest in Spiral Lands, it allowed me to recognize my position here in the United States, as a bystander. Because I’m a legal resident of this country, I have to take responsibility for certain things.

That question of responsibility, as we all know, is a really big one in Germany. In that way, my approach to things is really particular, with sensitivity toward responsibility and the sociopolitical realm that I work and exist in. The notion of collective responsibility is not very widespread in this country even though individual responsibility is so fetishized. Also the idea that you are responsible for the world around you as an individual, for bettering your community, is not something that is taught or emphasized here. In that way, I feel my approach is different.

Van Tomme: Would you say that that’s something you would like to point to with your work?

Geyer: Partly yes. All my work is highly invested in a conscious staging of an audience toward it. Sometimes that’s more visible than others, but there’s a very particular way in which I create a space for viewing and relating to my work. For example, in Spiral Lands, the first chapter is photographs and texts on the wall. The text implies the viewer in a certain way, but then there’s also a footnote pamphlet that you can take with you. It’s a massive document of 138 footnotes that are expansive and detailed; they’re the subtext to the at times poetic text that is displayed next to the photographs. So, what you as the viewer can take with you from the museum is a subtext, not the actual text. The idea is that you make up your own narrative and write your own story from it. That’s one simple way in which I engage the audience.

The second chapter of Spiral Lands addresses the role of science in the colonization process, mostly anthropology, ethnography, and history but also art. I dress up as an anthropologist and I give a polemic 50 minutes slide lecture. I walk up to the podium and I state strongly and clearly: “We are all to be held accountable,” and then I go on with “Good evening,” and start the lecture. It’s not just me giving an artist talk. It’s me being dressed in a suit that turns the entire setting into a performance. The format of the slide lecture very obviously becomes part of the piece as people become transformed into audience members.

My work is very much about the way in which people get involved with the themes I’m working with. People always ask me what Native Americans or indigenous people think about my work. Depending where I speak I will respond: “You are the population I’m talking about in this work. It’s about the Western perspective and the European-American take on the history of this land. My work looks at the way in which this history is shaped and how that process is part of colonialization and how it until today successfully distances individuals from it.”

Van Tomme: You often make use of language, not only literally text but also the language of educational systems, to stage your projects. Can you explain what specific role this plays in your work? Why do you choose such almost didactic settings?

Geyer: I would say that my work is more informed by literature than pedagogy, because I’m more invested in storytelling as a way of revealing information. But you’re right; I’ve used the setting of the educational lecture or the lecture room a few times. For me it’s also about psychology, about engaging an audience in a museum context. To achieve that I play with the experiences we all share. When you set up a school situation, people get silent; they listen. There is a certain comfort when sitting in a slide lecture: you’re in the dark with your own thoughts and you’re being told something.

I very much see my work as a way of poetic document making. I feel that there is a massive struggle over the historic moment: who gets to write history, whose voices are heard? The New York Times sometimes features cover articles claiming something and then two days later at the bottom of the ninth page, there is a little correction saying that what they said was actually inaccurate. Yet at that moment, it can already be imprinted into cultural memory; it becomes a part of how the moment is understood. Especially having experienced New York City in the fall of 2001, I am sure there were moments when anybody felt her or his memory was being rewritten by the media and by politicians. Even as a very conscious observer of what was happening, I felt that my very particular memory of the situation was constantly challenged by what the news was saying about it.

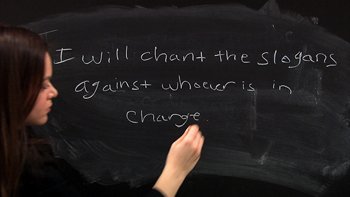

Andrea Geyer/Sharon Hayes/Ashley Hunt/Katya Sander/David Thorne. 9 scripts from a Nation at War, 2007. Video still.

For me, art is a space in which historic moments can be documented in very complicated ways. Take, for example, Spiral Lands. No form of science could work in this way. This is not an academic work, because I’m doing improper things, combining all these different languages and sources. Art has its own intelligence that way. As an artist, I’m taking the liberty to document a moment in all of its complexities; it can be long and it doesn’t have to fit a certain format. I do feel that 9 Scripts From A Nation At War is very much capturing the United States between 2003-2007. It’s a big piece but that’s what was needed. If you do a video installation with 10 videos that accumulate to nine hours of footage, you are offering viewers a possibility to engage with the complexity of something. It has not one answer, one moral or one solution, but it offers a set of questions, answers and suggestions of what to do. This is how I see my work: an active way of creating memory of something through viewing. There are people who really work with pedagogy in their work and I don’t think I really do that. It’s just one element of how I use photography, literary writing, or the classical document. It’s just one element of all the elements that I have available to play and work with.

Van Tomme: You mentioned story telling. In which way should I understand that?

Geyer: I would say that I really lean towards oral tradition. There is something that I deeply respect about it, because within this tradition there is no history that exists outside of a person speaking. The place, the origin, from which a history is told is always part of the story itself. It also implies that there is a listener. Oral tradition only works if there is somebody actively listening and learning the story. There is this saying that there is no use of listening to a story if you don’t learn to retell it. Maybe that’s what I’m really interested in. Every time a story is told it shifts, but it also stays true to itself. It exists in multiple layers, in repetition. I like the idea of a repetition that goes backwards, that the story has been told before, and that it simultaneously also projects forward, into the future, that it will be told again. This reaching of the present moment into the past and into the future, and the consciousness of that in the moment of telling it is what I’m interested in, also in my work. Art can create a collective experience, even if it hasn’t a crowd in front of it. The repetition of its viewing creates a community that has seen the work and shares an experience. It becomes collective even though it is a singular moment.

Van Tomme: Do you have a particular audience in mind when you create an art piece?

From Andrea Geyer, Interim, 2002. 80-page newspaper with photographs and text.

Geyer: It depends on the project I’m working on. Started in the summer of 2001, Interim was a work dealing with being an immigrant in the United States. After September 11, this became really different. The work is a newspaper; it’s the story of a female character that comes from a rural area into an urban area and then at the end of the story leaves the city again. The narrative is intercepted with tips from handbooks for immigrants, about how to assimilate into the culture. It was first shown at Manifesta in Frankfurt in 2002 and there the project was very much understood as a critical travel experience. The photographs are all taken after September 11 in New York. They’re very benign photographs, they’re not very sensational but they just show cityscapes in this medium-range distance, and people looked at them as pictures of New York.

One year later I showed them at the Whitney Museum in a show called The American Effect, analyzing the effect that America has on foreigners and in foreign countries, and suddenly it was read as a document of September 11. When people saw the photographs, they recognized details, they could read them differently, given their knowledge. Take for example the wet streets. People immediately knew these images were taken in the three months after September 11, because during that time the streets were washed every night to get the dust off the city. In almost every photograph there is a barricade. There is a picture of the skyline in which you see the empty spot, and, in another, an army battalion walks down Church Street. The piece worked for its own sake in Europe in 2002 and sensitive viewers saw what it was doing, but I feel that the work amplifies differently in different places.

I’m really critical about the notion of so-called international art, the idea that everything is translatable everywhere. I don’t think so. You can show things at other places and they can activate something, but you have to be aware of this difference and take account for that.

Van Tomme: In the end, does it matter to you how people regard your work, whether they consider it art or activism?

Geyer: It is art. I also work as an activist and these are two different things — I’ve gotten in trouble saying that publicly. My works exist within the realm of culture (and how this relates to politics) and not in the realm of activism, even though they at times employ activist strategies. I feel this difference is extremely important, because when I work as an activist my goals have to be clear, defined and efficient. They have to reach who needs to be reached. Activist actions have a limit or frame of what they want to achieve. It’s a much more pragmatic and efficient practice. Art can include similar notions but can linger, be dialectical, durational; it exists and is encountered over a long period of time.