The 2016 presidential election brought increased scrutiny of the private philanthropic foundations controlled by candidates Clinton and Trump and their families.

We should exercise similar oversight of the larger taxpayer-subsidized philanthropic sector to ensure it is serving its historic public purpose.

As wealth inequality has grown over the last several decades, so has the number of private foundations and mega-donor gifts. Since 1993, the number of private grant-making foundations doubled from 43,956 to 86,726 in 2014, as wealthy families establish institutions for giving.

At first blush, this appears to be positive development, as the affluent “give back” a portion of the wealth gushing to the top. But there are also troubling trends that may imperil the independent nonprofit sector and the health of our democracy.

With growing frequency, philanthropic vehicles such as donor-advised funds and private foundations become an extension of private wealth and power and the narrow interests that control them. Hundreds of billions of dollars are now warehoused in privately held funds with scarce accountability.

The public has a legitimate interest in proper oversight of private charity. Taxpayers subsidize up to 50 cents of every dollar that is shifted into the charitable sector. The wealthier the donor, the greater the amount of revenue lost to income and estate taxation.

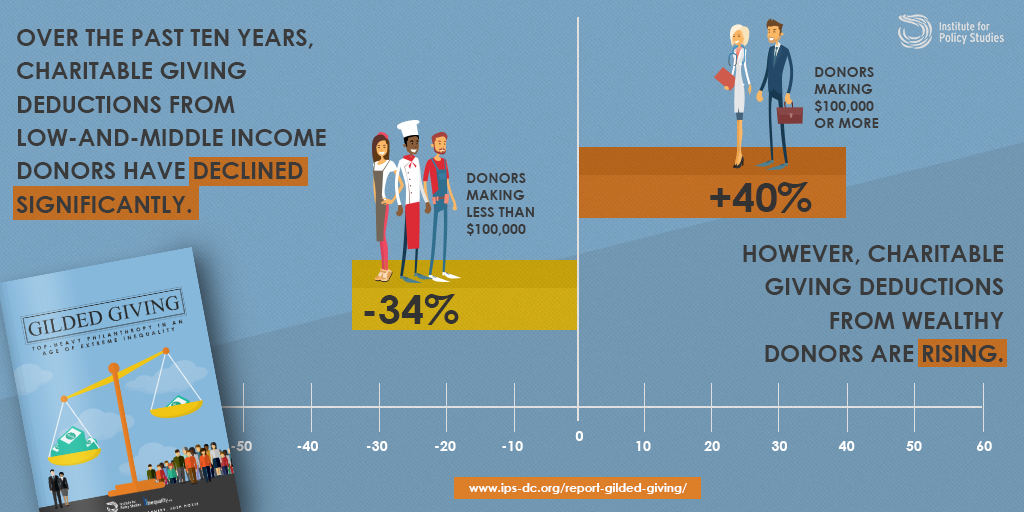

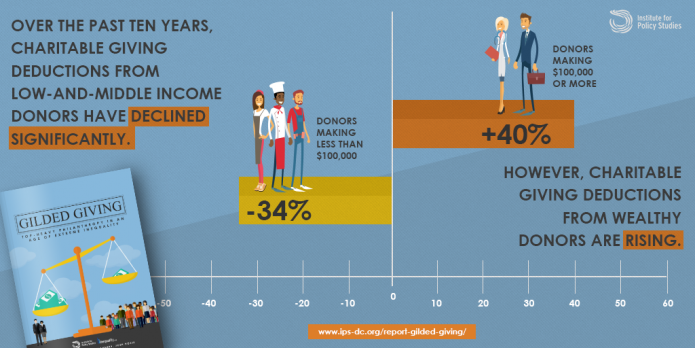

In a new report that I co-authored, “Gilded Giving: Top Heavy Philanthropy in an Age of Extreme Inequality,” we find that charities are increasingly reliant on larger donations from a smaller number of high net-worth donors, while receiving shrinking amounts of revenue from the vast population of donors at lower- and middle-income levels.

Charitable contributions from wealthy donors have increased significantly over the past decade. Between 2003 and 2013, itemized charitable contributions from people making $500,000 or more – roughly the top 1 percent of income earners in the United States – increased by 57 percent. And itemized contributions from people making $10 million or more increased by almost double that rate – 104 percent – over the same period.

Meanwhile, the number of donors giving at more modest donation levels has been steadily declining. From our research, we found low-dollar and mid-range donors to national public charities have declined by as much as 25 percent over the 10 years from 2005 to 2015.

Top-heavy giving poses a threat to the independent sector of nonprofit organizations that depend on broad-based support. Instead of relying on the “80/20 rule,” with 80 percent of an organization’s donations coming from 20 percent of their donors, we are drifting toward a “98/2 rule,” where most support comes from a handful of wealthy donors. This increases volatility and unpredictability in funding, but also requires nonprofit groups to cultivate and cater to the interests of a smaller number of donors, increasing the risk of mission drift.

If current inequality trends continue, philanthropy will become increasingly top heavy, with large proportions of charitable revenue coming from a precious number of wealthy donors.

Charities are already struggling to fill gaps left by cuts in government services and to address such dauntingly large social concerns as poverty, inequality and environmental destruction – so more revenue will naturally be welcomed. But our independent sector will suffer in a future of billionaire-driven philanthropy along side government budget cuts and austerity measures.

Without intervention, we will drift further toward an oligarchy of wealth and power, with some charitable entities becoming an extension of this power.

The last time we overhauled the legal framework for the philanthropic sector was in 1969, a period of relative equality in U.S. history. We need to modernize the rules governing charitable giving to encourage broader giving, protect the health of the independent sector, discourage the warehousing of wealth in private foundations and donor-advised funds and increase accountability to protect the public interest and the integrity of our tax system.

We have an opportunity now to address the risks of top-heavy philanthropy while rewarding the natural positive impulse of individuals and families to share the wealth.