Several decades ago, three expert nuclear engineers told a congressional panel why they decided to quit: “We could no longer justify devoting our life energies to the continued development and expansion of nuclear fission power — a system we believe to be so dangerous that it now threatens the very existence of life on this planet.”

The Joint Committee on Atomic Energy heard that testimony in 1977, when the conventional wisdom was still hailing “the peaceful atom” as a flawless marvel. During the same year, solid information convinced me to move from concern to action against nuclear power.

By the time the 1979 accident at the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant came close to rendering much of central Pennsylvania uninhabitable, I was nearly two years into full-time anti-nuclear work that included public education, civic activism, and nonviolent direct action. Given what was at stake, I didn’t mind spending a month in jail for civil disobedience.

More than 30 years later, the ongoing disaster at Japan’s Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear reactors underscores the grim realities of nuclear power, ranging from catastrophic reactor accidents to highly radioactive waste that will remain deadly for many thousands of years.

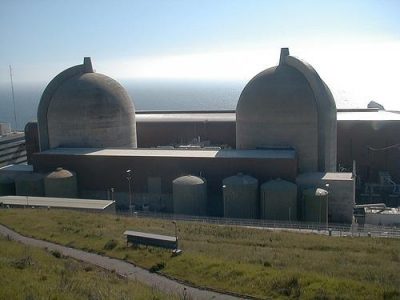

Diablo Canyon nuclear plant. Photograph by Nick Kocharhook.

Such inherent dangers are all too close to home in California. My home state’s two nuclear power plants — Diablo Canyon at San Luis Obispo and San Onofre farther south — are both located on major earthquake faults along the coast.

The overall record of Diablo Canyon’s owner and operator, utility company PG&E, hardly inspires confidence. And recent events in Japan showed that official assurances can become worthless after a big quake and tsunami.

Continuing radioactive leaks from Fukushima are extensive and multifaceted. The authoritative journal Nature reported in late May that “some scientists are simply floating the idea of turning Fukushima into a nuclear graveyard,” but “given the plant’s location on the coast, storing the waste there for millennia may be unrealistic.”

Here at home, I fundamentally disagree with the official mantra that California’s two nuclear power plants should keep operating while federal agencies conduct “studies” to determine whether those nukes are risky enough to warrant closure.

The U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission and the Energy Department have been avidly promoting nuclear power for decades. Periodic calls for more “studies” have kicked the radioactive can down the road.

I reject the notion that we should wait for such nuclear-enthralled agencies to tell us whether nuclear power is an acceptable risk for Californians.

As the director of the National Citizens Hearings for Radiation Victims in 1980, I learned a lot about patterns of official enabling of the nuclear industry — with awful results for human health and the environment.

Similar patterns persist today.

In contrast, the German government has seen the light. Chancellor Angela Merkel has announced a reversal of policy — moving to shut down nuclear power instead of trying to expand it.

The decision to immediately close eight German nuclear power plants and shutter the rest by 2022 came in a country that had been getting 23 percent of its electricity from nukes.

Here in California, we’re less reliant on this Faustian technology, getting just 15 percent of our electricity from nuclear power. The state has a lot of excess generating capacity from other sources, but far better choices for the environment are within our grasp.

Effective conservation options are readily available, and widespread use of renewable alternatives like solar power is within reach. What we need is the political will to fight for serious public investment in sustainable energy and a non-nuclear future.