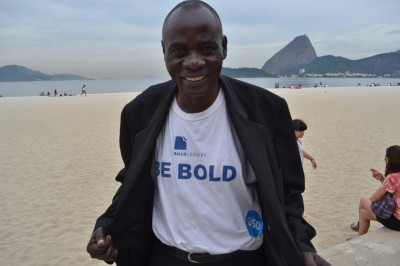

Kaganga John in Rio

“We aren’t leaving this conference without a concrete step toward sustainable development for your village,” I told Kaganga, “even if that means we don’t sleep.”

I refreshed the screen, and both our faces lit up as I opened the email that had just arrived. “The Ugandan negotiation team heard about your panel on human security and sustainable development and they want to meet with us,” I said. We high-fived each other and started drafting our response.

Kaganga and I met last January while I was in Uganda launching the Million Person Project, which facilitates global relationships and works one-on-one with change makers to support their programs. The second I saw Kaganga’s work it was clear to me that this man — his sustainable farming practices, his community empowerment models, and his grassroots education programs — needed to be supported on an international level.

I asked Kaganga what he needed. He suggested we go together to the UN Conference on Sustainable Development in Brazil. My eyes widened, thinking of the logistical feat it would take to get us both there. But he wasn’t finished. He then suggested that in Rio we should make connections with leaders of organizations and foundations that could ensure the long-term sustainability of his programs. Kaganga, who is 57 years old, has done all his work by collecting small membership fees from his community, and now that he’s growing older he wants to guarantee that this work will continue once h’s gone.

By combining frequent flier miles and a couple of $500 donations, and by talking our way into a shared room at a friend’s rented house, we got the funding to attend. Kaganga sold his computer to pay his visa fees, believing that the connections he’d make in Brazil would exceed the value of a laptop.

Hope and Despair at the UN

There is no place on earth like a UN conference. It is a truly global gathering, with people from nearly every nation in the world working side by side, eating together, and sharing their work, stories, and inspiration. But politically they are a difficult place to stay inspired. I had attended two of them before: COP15 and COP17. Both of those conferences ended in political stalemate, and I returned home bruised from dodging pepper spray in a crowd in Copenhagen and being physically escorted out of the conference hall in Durban.

This time, I told myself, I would go with the resigned assumption that nothing significant would happen. I would just focus on what I knew I could control: networking and relationship building.

But as I walked through the massive front entryway, with Kaganga John and my friends from the international climate change organization, 350.org, by my side, saw the expansive stage decorated with every flag on the planet, and felt the energy of people from 200-plus nations whizzing through the hallways, I was seduced into thinking that this time, the leaders of the world would seize the moment, speak up for the poorest on the planet, and commit to judging economic progress by the health and wellbeing of our people and environment, and not by gross national product. I was seduced into thinking that they would be inspired by Kaganga’s story and find ways for their policies to support and replicate projects like his.

They did not seize the moment. And once again, I came home bruised, this time from a sit-in during the closing days, a sort of last-ditch attempt at calling attention to ourselves when it was clear that civil society’s demands were not being heard.

But I also came home with something else, something that I did not expect. I had a new source of hope and inspiration.

Kaganga John didn’t influence the outcome of the United Nations Sustainable Development document. But in a conference center where people are accustomed to generic powerpoints presented in a monotone voice by “experts,” Kaganga came armed with stories, heart, and a passion that turned the heads of ministers, diplomats, and conference attendees. By speaking fervently at side events about building a sustainable and just green economy in his community, he was able to fill his schedule with future conference calls and further correspondence with potential partners.

Since returning to Uganda three weeks ago, he has already heard from a partner to facilitate the opening of a technology and resource center so that local farmers can access up-to-date information and develop practices for tracking yields. With Kaganga’s enthusiastic follow-up, there is no telling what can come of these connections.

In Kassajere

Piece by piece, Kaganga John and the organization he co-founded, the Kikandwa Environmental Association (KEA), are moving their community toward sustainable development. When the organization was founded in 1999, their village, Kassejere, was really suffering. Kaganga John had moved away from his village as a teenager to pursue his education in the capital city, and when he returned, nearly 20 years later, what he saw was devastating.

The land had been severely degraded, changing weather patterns had left farmers unable to depend on traditional planting schedules, food yields were at a historic low, and many villagers were going hungry. The roads had been washed out and the surrounding forests had been cut to the ground for firewood and charcoal burning. Children were dropping out of school because it was a five-kilometer walk to the nearest classroom. So Kaganga John decided to call a meeting and bring together the community to help re-build his village.

Since that meeting the situation in Kassejere has significantly improved. The village now has a school attended by 250 students. And although the teachers and school staff are all volunteer and they do not have buildings, the school has the second highest exam pass rates in the district.

On the environmental side, KEA has successfully pushed the Ugandan government to replant hundreds of hectares of forests. KEA lobbied officials both locally and nationally, and organized people—village by village—to use their collective voice to advocate for the replanting. KEA has also conducted hundreds on environmental management workshops in the region, working with farmers to develop sustainable farming practices such as food diversity, seed saving, climate change mitigation, and crop rotation. The organization has launched a farmer innovation program that supports farmers to develop small-scale innovations, such as herbal pesticides, water collection devices, and drought-resistant planting methods. Their community is now becoming a model community for responsible environmental management.

In 20 years they have accomplished a lot. But they are now working to develop global partnerships to ensure the long-term sustainability of their work. Kaganga John sees global partnerships as a key piece of the puzzle, not just for financial and technical farming support but also because he believes that reaching out and building relationships across borders is the only way we can solve problems as overwhelming and far-reaching as climate change and sustainable development.

That is how he came across the Million Person Project, which shares his philosophy. The Million Person Project was developed out of a simple belief that, just as the problems plaguing our planet are inherently connected, so are the solutions. Only by connecting change makers to each other around the world can significant progress be achieved. The project connects an anti-plastic campaign in Vietnam to anti-plastic campaigns in New York and San Francisco to share strategies. It introduces a grant maker to a potential grantee. It connects a man who runs a school in a developing country, like Kaganga John, to an organization that help construct schools. The Million Person Project is based in the United States and works both on the ground and virtually to facilitate these connections.

Remaking Global Partnerships

Rio+20 was so named because it occurred 20 years after the first Earth Summit was held in 1992. The world spent those 20 years holding periodic intercessionals, organizing working groups, and drafting and re-drafting policy. And nothing was gained.

If we had put a fraction of the energy we spent in preparation for Rio+20 into supporting individuals and communities in their own small-scale pursuits of sustainability, we would change the situation. Just consider what Kaganga John did in 20 years and what he might have accomplished with more global assistance.

I am not suggesting charity. If you run an online publication, invite farmers on the ground to submit. If you run a women’s policy organization, forgo one invitation to speak on a panel and invite a grassroots leader in your place. If you are working tirelessly on primary education policy in developing countries, partner with schools to ensure they have up-to-date curriculums.

In today’s world, global relationships are so possible, so simple. People halfway across the globe are no longer unreachable, and we do not have to create international policy to partner with them. Think of what can happen between now and Rio+40 if we don’t wait for the next big UN meeting to work with people from around the world and instead create new alliances for action.

Connections are powerful. In fact, they’re all we have.