It is hard to overstate just how deeply unpopular the United States is in the Muslim world.

It is hard to overstate just how deeply unpopular the United States is in the Muslim world.

A 2008 poll of six majority Muslim countries found that overwhelmingly large portions of the population, ranging from 71 percent in Morocco to 87 percent in Egypt, held unfavorable opinions of the United States. A 2009 poll in Pakistan revealed that 64 percent of the public views the United States as an outright enemy.

So it is a curious paradox that, despite the antagonistic and sometimes violent relationship between the United States and the Muslim world, Muslims here have fared relatively well. According to a 2009 Gallup poll, 41 percent of Muslims in the United States describe themselves as “thriving” — only five percentage points below the national average, and higher than the percentage reported in any Muslim country aside from Saudi Arabia. A full 40 percent say they have at least a college degree, making them the second-most educated religious group after Jews (at 61 percent).

Further, U.S. Muslim women, after their Jewish counterparts, are the most highly educated female religious group in the country, and Muslim economic gender parity is the nation’s most egalitarian at both the low and high ends of the spectrum.

An earlier 2007 Pew study painted a similar picture. Titled Muslim Americans: Middle Class and Mostly Mainstream, it described the Muslim minority in the United States as “largely assimilated, happy with their lives, and moderate with respect to many of the issues that have divided Muslims and Westerners around the world.”

Events of the last few months, however, have called into question the pertinence, if not the validity, of that rosy general assessment. Though terrorist suspects had in the past almost always been foreigners, several of those implicated in more recent plots against American soldiers and civilians were Muslims born or raised in the United States.

U.S. Muslims as a Domestic Threat

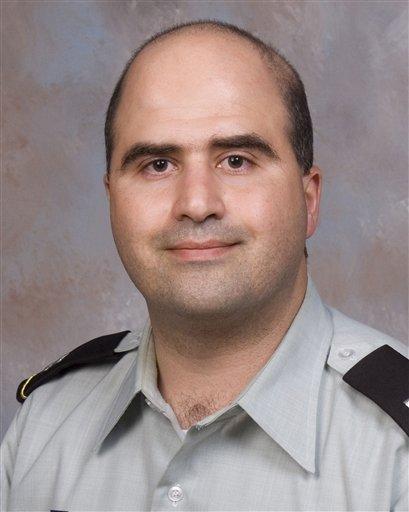

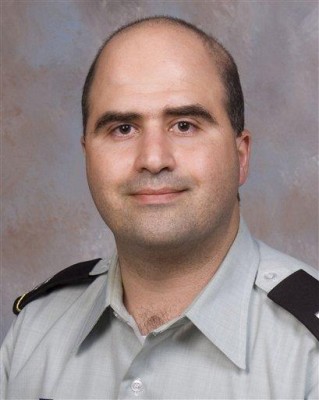

The November 2009 incident at Fort Hood, the Texas Army base where Maj. Nidal Hasan is suspected of gunning down 10 fellow soldiers, presents the most striking case. A steady stream of unsuccessful plots has also garnered attention: the 25-year-old Queens coffee vendor who pleaded guilty to a conspiracy to destroy the New York City subway system in September 2009; the five youths who left Washington D.C. in December 2009 allegedly to join a Pakistani militant group; the middle-aged, self-proclaimed convert from Philadelphia who reportedly planned to kill a Swedish cartoonist last month; the 25-year-old New Jersey man who was caught in Yemen a week later purportedly trying to join al-Qaeda.

And just this Monday, one day after the most recent terror scare, police arrested a 30-year-old naturalized U.S. citizen from Pakistan; they suspect him of having loaded a sport utility vehicle with the bomb-making materials that were designed to explode in the most iconic part of our country’s most celebrated metropolis: Times Square, New York City.

Although attention lavished on individual cases should not obscure the broader picture — of the 14,000 homicides committed in the United States last year, only 14 are attributable to Muslim militancy — the sudden swell of homegrown Muslim extremism is significant. Most acutely, it has thrust into the foreground questions that have lingered in the minds of many Americans since September 11: Does Islam cause terrorism? Are all Muslims potential terrorists?

For conservatives, the latest string of incidents will only harden their conviction that the answer is a resolute “yes.” They have long insisted that Islamist terror isn’t fueled by policy or circumstance but is instead an article of the Islamic faith. And where no trace of terror can be found, conservatives have gleefully cooked up charges against Muslims, as illustrated by the smear campaigns directed at Swiss academic Tariq Ramadan, former Obama adviser Mazen Asbahi, Organization of Islamic Conference envoy Rashad Hussain , and the original principal of New York City’s first Arabic-language school, Debbie Almontasser.

For some liberals, too, the recent developments will cause unease. It was one thing to face attacks from abroad, but the presence of a homegrown Muslim threat seems to shatter the old shibboleths about multiculturalism and diversity. Some on the left had neatly apportioned Muslims into categories of “good” and “bad,” and the old paradigm that accepted only “assimilated” and “modernized” Muslims as safe is now under threat.

This liberal unease has already reached an advanced stage in Britain, typified by the writer Martin Amis, who insists that he despises “Islamism” but not Islam. This qualification notwithstanding, Amis regularly lets his mask slip with puffed-up declamations such as this one: “[N]o doubt the impulse toward rational inquiry is by now very weak in the rank and file of the Muslim male.”

In fact, there is a shared element between conservative and liberal views on Islamist extremism: certainty that the main problem lies with Muslims themselves.

Their Violence, Our Violence

The palatable and politically safe answers — for conservatives, that Muslims are inherently violent, and for left-liberals, that only a small minority is violent — have always skirted around one important detail: our own violence.

This is no surprise. The notion that our violence motivates terrorism has always lost out to the notion that terror is absent from our violence. It was George Orwell who observed in 1945 that, “the nationalist not only does not disapprove of atrocities committed by his own side, but he has a remarkable capacity for not even hearing about them.”

But this “remarkable capacity” is not shared by everyone. Civilian deaths and accounts of torture from Iraq, Afghanistan, and Palestine have fueled the radicalization of a minority of Muslims abroad, and it was only a matter of time before it produced the same effect on a minority of Muslims here, too.

It is only now, amid this growing domestic radicalization, that we are seeing some willingness to cure the deafness Orwell once wrote about.

Hope for the Future?

In a December 2009 New York Times article, top U.S. terrorism experts spoke bluntly about what motivates these attacks. Bruce Hoffman, a terrorism researcher at Georgetown University, noted that American military interventionism was the only logical reason for the spike in homegrown terror cases. “The longer we’ve been in Iraq and Afghanistan, the more some susceptible young men are coming to believe that it’s their duty to take up arms to defend their fellow Muslims,” he said. Robert Liken, from the Nixon Center in Washington D.C., echoed that theme: “Just the length of U.S. involvement in these countries is provoking more Muslim Americans to react.”

In March, the Center for Strategic and International Studies went a step farther. In its 22-page report on homegrown terrorism, it not only recognized the motives of homegrown terrorist suspects but advised the government to shift its policy accordingly:

[S]everal of those arrested last fall seemed to harbor the belief that the United States is at war with Islam…The United States must continue to work to puncture this narrative. White House officials already have discarded phrases like ‘war on radical Islam.’ But ultimately, the United States needs to go further than this, because al Qaeda seizes on more than just U.S. rhetoric to galvanize support for its agenda; the group also points to America’s military presence in Muslim countries as evidence for its preferred narrative. The United States, then, should consider how to balance the need to combat global terrorism with the drawbacks of large-scale, direct military intervention.

That study, along with a January report co-issued by Duke University and the University of North Carolina, also urged the government to open more lines of communication with the Muslim community.

The Obama administration at least appears to be listening on both counts.

In an April 14 speech, the president broke with a long tradition of enforced silence by asserting that the Israeli-Palestinian crisis has ended up “costing us significantly in terms of both blood and treasure.” Ignoring the cacophony of neoconservative complaints, the administration has also allowed Tariq Ramadan back into the United States and defended its choice of Rashad Hussain as special envoy to the Organization of the Islamic Conference.

Moreover, Arab and Muslim community leaders feel they are finally being heard. “For the first time in eight years, we have the opportunity to meet, engage, discuss, disagree, but have an impact on policy,” said James Zogby, president of the Arab American Institute in Washington. “We’re being made to feel a part of that process and that there is somebody listening.”

These moves are encouraging. That some Muslim extremists now hail from our own country has, paradoxically, brought us closer to curbing terrorism. It is doubtless more difficult to conjure fantastic and absurd explanations for suicide attacks — endless virgins, inexplicable evil, exotic culture — when those carrying out such attacks are integrated and functioning members of our society rather than easily caricatured foreigners.

If the Obama administration follows through on its hesitant first steps, scaling down its military interventions, tempering its support for Israeli colonialism, and increasing engagement efforts with Muslims here and elsewhere, it will lay down a solid framework for building trust and respect.

As Audrey Kurth Cronin of the National War College observed, those assets are valuable in combating militancy: “To me, the most interesting thing about the five [Virginians] is that it was their parents that went immediately to the F.B.I. It was members of the American Muslim community that put a stop to whatever those men may have been planning.”

For ten years, America has hitched its foreign policy train to an engine of war and occupation. As a result, America’s standing in the Muslim world has declined disastrously. It’s long past time to switch tracks.