Throughout most of the past four years, Republicans imposed a moratorium on substantive debate that caused the vaulted chambers of Capitol Hill to function as little more than an echo chamber for the Administration’s Iraq policy. Democrats, cowed by fears of being portrayed as undercutting the troops, were largely silent. The few Democratic initiatives seeking to limit or otherwise interfere with President Bush’s dreams of unending war were routinely silenced and reconstruction oversight languished.

With the new Democratic congressional majority in place and President Bush’s approval ratings for handling the war hovering around 30%, however, there are suddenly real opportunities to bring an end to the senseless U.S. military adventure in Iraq. While some anti-war activists disagree over near-term tactics, the political strategy that can end the war is the same as it has always been. In order to find the least bad solution to the war and bring American troops home sooner rather than later, war opponents must avoid a circular firing squad and encourage moderate Republicans—especially Senators—to join the anti-war camp.

Where Congress Has Been: Oversight

War supporters often claim that congressional involvement in shaping foreign policy somehow infringes on the president’s commander-in-chief authority. This view is at odds with the U.S. Constitution and existing precedent. Congress has historically played an active role during American military engagements abroad, including during Kosovo, Bosnia, Haiti, Rwanda, Somalia, Panama, Nicaragua, Grenada, Lebanon, Vietnam, Korea, and especially throughout World War II, where the famous Truman Commission investigated war production fraud and saved the U.S. around $15 billion.

Under Republican management, Congress was derelict in its watchdog responsibilities throughout the past four years. “Congressional oversight of the executive across a range of policies, but especially on foreign and national security policy, has virtually collapsed,” conclude preeminent congressional scholars Norman Ornstein and Thomas Mann in a recent Foreign Affairs article. Several egregious examples illustrate the sorry state of affairs.

While the Republican Congress took 140 hours of testimony on whether President Clinton was using his Christmas mailing list for soliciting potential contributors in the mid-1990s, House Republicans received only 12 hours of testimony on the Abu Ghraib scandal. In March 2003, Lt. Gen. Jay Garner, the first U.S. civilian administrator in Iraq, unceremoniously canceled appearances before the Senate Foreign Relations and Armed Services Committees where he was scheduled to discuss post-invasion planning, a slight Sen. Dick Lugar (R-IN) called a “fiasco.” And, while political grandstanding during hearings is standard for many members of Congress, some hearings that did actually occur on Iraq were downright farcical. The title of a House Foreign Affairs Committee hearing on February 26, 2003, pretty much says it all: “Russia’s Policies Toward the Axis of Evil: Money and Geopolitics in Iraq and Iran.”

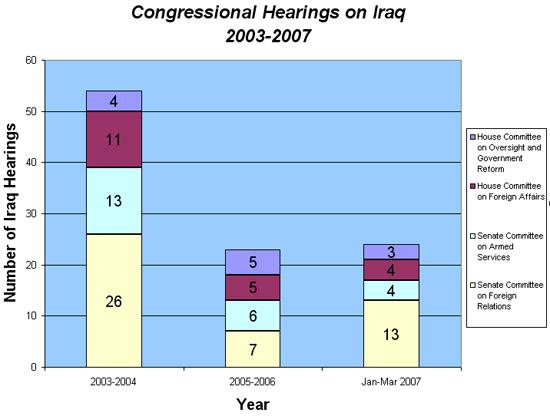

The chart below displays the number of Iraq oversight hearings held by four key committees during the 108th, 109th, and first few months of the 110th Congresses.

While 2003-2004 doesn’t appear quite as devoid of oversight as most anti-war activists probably remember (thanks in large part to leadership by former Senate Foreign Relations Committee chairman Dick Lugar), there have already been more Iraq hearings during the first two months of 2007 than there were in all of 2005 and 2006 combined. Through the beginning of March 2007, 71 hearings on Iraq had taken place according to Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s office.

Where Congress Has Been: Legislation

Any discussion of legislation must begin with the original war authorization in the House, which passed 296–133 on October 10, 2002, after 17 hours of debate. Contrary to assertions by war supporters like Rep. Todd Akin (R-MO), who vacuously argued that congressional support for the war was “nearly unanimous” during a February 2007 Washington Journal interview, 126 of 212 Democrats (59%) voted in opposition and six brave Republicans recorded “Nay” votes.

The Senate, usually more conducive to independent-minded legislators, fared worse than the House in opposing the war. Only one Republican, Sen. Lincoln Chafee (R-RI), voted against the authorization, arguing during floor debate on October 9, 2003 that military action in Iraq could trigger “a rise in terrorism” and that Saddam Hussein was best dealt with “in concert with our allies and within the confines of the United Nations.” Twenty-one of 50 Democrats (42%) along with one Independent eventually registered opposition (the final vote was 23–77), although five of the Democratic naysayers are now no longer in office: Graham (FL), Sarbanes (MD), Dayton (MN), and Corzine (NJ) retired and Wellstone (MN) passed away a few weeks after the Iraq vote.

Following passage of the war authorization, Republicans enforced a de facto gag order on resolutions critical of any aspect of the war. The overwhelming military success of the initial invasion combined with unyielding administration rhetoric, including the much lampooned “Mission Accomplished” gaffe, to constrain congressional Democrats’ anti-war activism. Much of the party’s energy went into trying to defeat Bush in the 2004 presidential election.

Sen. John Kerry’s (D-MA) presidential campaign loss triggered a Democratic crisis best remembered by former Howard Dean campaign manager Joe Trippi’s ominous warnings about becoming a “permanent minority party.” Faced with the dim prospect of four more years under the Bush administration, congressional Democrats decided it was time to take a stand on Iraq and started putting members of both parties on record with increasingly difficult votes.

In May 2005, Rep. Lynn Woolsey (D-CA) introduced an amendment to the Defense Authorization Act calling on President Bush to submit a plan for the withdrawal of U.S. military forces from Iraq. Although it failed 128–300, five Republicans crossed party lines and 60% of Democrats (122/202) voted “Yea,” demonstrating that while war opponents were far from agreeing on a unified strategy, their anti-war resolve hadn’t evaporated despite the January 2005 Iraqi elections being spun by President Bush as a “resounding success” where Iraqis had “taken rightful control of their country’s destiny” and proven “equal to the challenge.”

By June 2006, congressional midterm elections loomed and the violence in Iraq was metastasizing into an all-out civil war following the February bombing of the Golden Mosque in Samarra. Democrats and Republicans alike speculated that a heated legislative summer showdown would help cement their side’s electoral superiority on the ever controversial Iraq issue. “When [voters] say they want significant change in America, and you ask them what they’re talking about, their answer is Iraq,” then-minority whip Dick Durbin (D-IL) commented.

Things came to a head in the House over a politically charged Rep. Henry Hyde (R-IL) resolution recommitting the U.S. to “a sovereign, free, secure, and united Iraq” and opposing any “arbitrary” date for withdrawing U.S. forces. The final roll call came down 256 – 153: three Republicans broke with their party leadership to join 149 Democrats in opposition. While the final tally was disappointing, 35% of the House voted “Nay”—an increase from the meager 29% supporting Woolsey’s May 2005 anti-war resolution—and Democrats were much more unified, with 74% logging anti-war votes.

The Senate considered two critical amendments on June 22, 2006: a Levin (D-MI)-Reed (D-RI) proposal calling for the phased redeployment of American forces and a Kerry (D-MA)-Feingold (D-WI)-Boxer (D-CA) effort mandating that troop withdrawal be completed by July 1, 2007. The Levin-Reed plan was rejected 39–60 but an encouraging 37 of 44 Democrats (84%) voted in favor. The Kerry-Feingold-Boxer legislation did not fare as well. It was beaten back 13–86 with support from only 12 Democrats (27%).

Although June 2006 was disheartening for war opponents due to the legislative trouncing, it also signaled the beginning of a congressional revolt against the war. Republicans shot themselves in the foot by becoming irreversibly tied to an unpopular president seemingly unaware of the deteriorating conditions on the ground in Iraq. The November 2006 midterm electoral coup bore out the foresight of the Democrats’ savvy June maneuvering.

A significant anti-war victory was achieved by the new Democratic majority in February 2007 with the passage of a Rep. Ike Skelton (D-MO) resolution condemning the proposed escalation in Iraq by a 246–182 margin. Seventeen Republicans crossed the aisle to vote in favor along with 98% of all House Democrats (only Marshall-GA and Taylor-MS voted in opposition).

The next day, during a rare Saturday session before the President Day’s recess, the Senate barely failed to invoke cloture on proceeding to the just-passed House resolution. The final vote came down 56–34 with seven Republicans voting in favor and 48 of 49 Democrats (98%) supporting the resolution (Johnson-SD was recovering from surgery).

Where Congress Can Go: Political Strategy

As Congress moves into the critical supplemental appropriations process in March, the Democratic congressional leadership will attempt to maneuver around obstructionist war supporters in a way that makes sense both politically and in terms of U.S. national security. There are many things to be encouraged about already. For example, Congress has introduced more than 50 pieces of Iraq legislationduring the first two months of 2007. By comparison, only 57 resolutions on the Vietnam War were introduced during 1971 and 1972 combined.

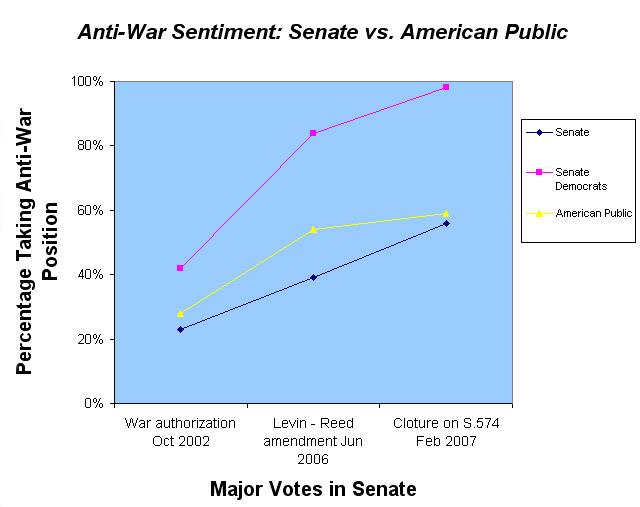

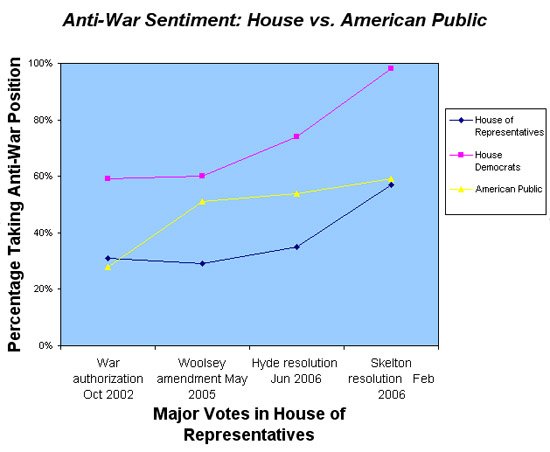

The following graphs illustrate the evolution of anti-war sentiment in Congress and the American public, offering some guidance for future priorities.

Two things immediately jump out. First, except for the initial stasis among House Democrats between October 2002 and May 2005, congressional Democrats’ conversion to the anti-war position has outpaced the American public. This refutes assertions that Democrats somehow “don’t get it” or are out of touch with America’s hatred of the war. This is critical to understand because in February 2007, Democrats became a virtual monolith by almost unanimously disapproving of the troop escalation in both chambers. Activists and the Democratic leadership may continue to persuade members to embrace increasingly coercive legislative techniques such as cutting off funding, but the intra-party “you should oppose the war” proselytizing phase has come and gone.

Second, while public opposition to the war has continued to steadily rise over the past four years, recent voting and polling proves that Congress as a whole is on the same page as the American public; that is, they oppose the war but they’re not sure how to go about ending it. In February 2007, 59% of Americans thought the war in Iraq “wasn’t worth it,” 57% of the House voted in favor of the non-binding anti-escalation resolution, and 56% of the Senate voted to consider the same resolution. The American public, House, and Senate were therefore within three percentage points of one another in terms of opposing the war/escalation.

Uncertainty about how the U.S. should get out of Iraq, already well-documented in Congress, was further revealed within the American public in a February 27 Washington Post-ABC News poll. While two-thirds of respondents opposed President Bush’s troop surge and 53% supported a deadline for troop withdrawal—the first time a majority has favored setting a deadline—a slim majority of 51% remained opposed to restricting funding for the war.

It is not illogical to assume that there is a certain immovable portion of the American public, people who think that we should support President Bush and the war in Iraq no matter what. The graphs above perfectly illustrate that opposition to the war has flattened out within the American public but is accelerating within both chambers of Congress. Since these “immovables” will likely never be swayed to oppose the war, anti-war activists should focus on pushing opposition to the war within Congress above the American public, a phenomenon that occurred before during the war authorization vote in the House. This strategy will permit Congress—led by 100% of Democrats and a solid but growing posse of Republican war opponents—to work towards ending the war because they’ll have the votes necessary to invoke cloture in the Senate and overcome any veto from President Bush.

The only way to attract Republicans to support anti-war legislation is to convince more of their constituents (especially the all-important independents) that the war in Iraq is damaging vital U.S. national security interests. While some of this can be done through awareness raising in media and working with allies on Capitol Hill, events on the ground in Iraq—which experts agree are likely to continue to deteriorate—will play the largest role. Recent conversions to the anti-war position by Senate Republicans with moderate constituencies up for reelection in 2008 (Coleman-MN, Collins-ME, Hagel-NE, Smith-OR, Warner-VA) demonstrate that vulnerable Republican incumbents may be strongly persuaded to oppose the war when their political lives flash before their eyes.

The Democratic midterm victories relieved a lot of pent up frustration, but the short-lived catharsis hasn’t quelled exhortations by anti-war activists that things just aren’t moving quickly enough. While speaking out against Democratic foot dragging on Iraq is necessary in order to maintain the sense of urgency, incrementalism is the modus operandi of American foreign policy and anti-war activists must remain unified and encourage moderate Republicans—especially Senators—to join the anti-war camp and press for the return of U.S. troops as soon as possible. Success does not require ideological purity, but it does require that war opponents of all stripes ditch the internecine turf battles and try not to make it obvious that we are not yet comfortable being in the majority.