If you were born before 1950, you probably remember what happened in October 1962. If you were born after that fateful month, you’re lucky.

Exactly half a century ago, the United States and the Soviet Union reached the brink of a deadly nuclear showdown during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Appropriately, Barack Obama and Mitt Romney’s foreign policy debate will take place October 22 — exactly 50 years after President John F. Kennedy’s most dramatic television address to the nation. That frank talk ushered in a week of heightened anxiety, to put it mildly, around the world. With the question of Iran’s nuclear ambitions now on our minds, I hope Obama and Romney will take this opportunity to weigh in on the lessons we’ve learned since 1962.

In the aftermath of Cuba’s 1959 revolution, the Kennedy administration was trying hard to topple Fidel Castro’s government. Washington imposed trade sanctions, experimented with sabotage, staged assassinations, and finally backed an ill-fated and poorly equipped guerrilla invasion in Cuba’s Bay of Pigs. Instead of bringing Havana back into the U.S. sphere of influence, Cuba turned to the USSR for support.

Premier Nikita Khrushchev, acutely aware of the U.S. nuclear missiles based close to Soviet territory in Turkey, approved sending military aid, troops, and nuclear weapons to Cuba. Khrushchev sought to protect his new Caribbean ally and achieve nuclear deterrence on the cheap. Moscow had few long-range nuclear missiles at that time.

The crisis rapidly escalated after a U.S. spy plane discovered missile sites under construction on October 14, 1962. When Kennedy addressed the nation eight days later, he demanded that Moscow remove the missiles. Then he imposed a naval blockade.We know now that the crisis was a classic example of misperception and misunderstanding: the fog of war.

The Kennedy administration didn’t realize that Moscow had already stationed 162 nuclear warheads in Cuba as well as nuclear-armed torpedoes on its submarines. Russian leaders incorrectly thought that Washington would accept missiles in Cuba since Uncle Sam had missiles in Turkey, on the USSR’s doorstep. Both sides thought they understood the situation and the other side’s motives. They were wrong.

In retrospect, it’s clear that JFK’s top military advisers did him a disservice. Secret White House tapes made during the crisis reveal that his Joint Chiefs of Staff unanimously pressed for war. They hurled charges of “appeasement” in an effort to intimidate Kennedy into launching an attack on Cuba. At one point, after the commander-in-chief left the room, they can be heard mocking him.

It later emerged that both sides had grossly misunderstood the situation. We averted nuclear war more by accident than statesmanship. Robert McNamara, Kennedy’s Pentagon chief, later worked to abolish nuclear weapons worldwide. In the end, he concluded that, unless we take action, “the indefinite combination of human fallibility and nuclear weapons will destroy nations.”

What’s perhaps most alarming about the crisis is that both U.S. and Soviet leaders behaved as if the addition of nuclear weapons to the mix had little impact on how they handled the crisis. That’s why they allowed a dispute over a transient tactical advantage to endanger the entire planet, including generations yet unborn.

If that sounds insane, it should. It’s what Albert Einstein warned about in 1946, when he declared, “The unleashed power of the atom has changed everything save our modes of thinking, and we thus drift toward unparalleled catastrophe.”

Do you think either Romney or Obama would have done better than JFK during the crisis? Do you trust either one of them to be stewards of weapons quite capable of extinguishing life on the planet?

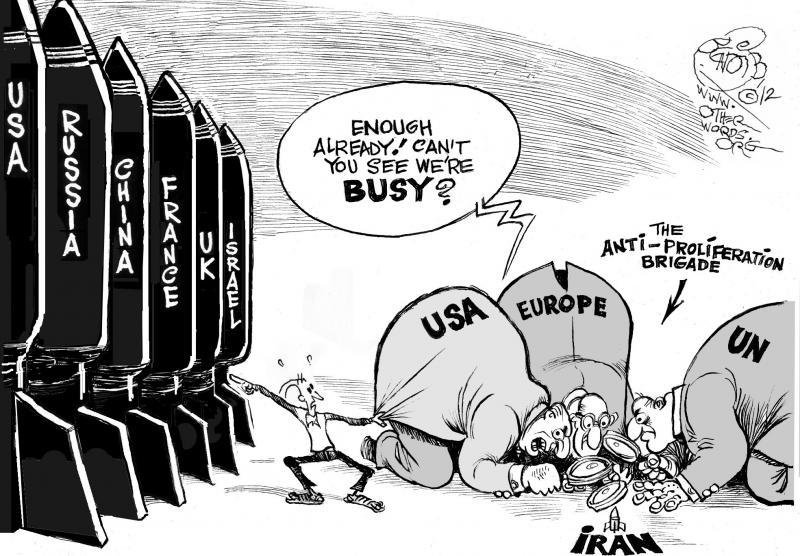

I sure don’t. So on this 50th anniversary of being more lucky than brilliant, let’s make a commitment to rid the Earth of nuclear weapons.