“So sure as the Idea and the existence of Property is admitted and established in society, Accumulations of it will be made, the Snow ball will grow as it rolls.”

John Adams, letter to Thomas Jefferson, July 16, 1814

Despite having cast feudal titles aside in the American Revolution, aristocracy has been with us in the United States since independence, as the statement above from John Adams, the nation’s second president, readily acknowledges.

Yet even though it has been ever-present, the US aristocracy—also known as “dynastic family wealth” and characterized by multi-generational, family holdings—is rarely analyzed. Indeed, its very existence has often been denied. For example, in a 1940 address, John Conant, then president of Harvard, said, “Until fairly recently it was taken for granted that the American republic could be described as classless,” willfully ignoring, for example, the plantation-based aristocratic system made possible by the enslavement of millions of Americans and sustained after the Civil War through a highly inequitable farm production system of sharecropping.

Even today, the US aristocracy gets scant attention. For sure, ever since Occupy Wall Street emerged a decade ago, the “top one percent” does. But this critique typically focuses on (somewhat) “self-made” billionaires—folks like Warren Buffett, Bill Gates, Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and Mark Zuckerberg. These folks are insanely rich, but while most grew up in well-to-do households, they were not born to great wealth.

There is, however, another group of people whose billionaire wealth is inherited. Meet US aristocracy, 2021 style. The five wealthiest dynastic families are the Walton (Walmart), Koch (Koch Industries), Mars, Cargill-MacMillan, and Lauder families—and there’s not a tech titan among them.

The story of these five families—and 45 others—is the focus of a new study released by the Institute for Policy Studies, titled Silver Spoon Oligarchs: How America’s 50 Largest Inherited-Wealth Dynasties Accelerate Inequality. Authored by a six-person team consisting of Chuck Collins, Joe Fitzgerald, Helen Flannery, Omar Ocampo, Sophia Paslaski, and Kalena Thomhave, the report builds on a December 2020 article by Forbes on dynastic wealth and documents the staying power of many of America’s leading family dynasties. Combined, the 50 families reviewed have wealth exceeding $1.2 trillion. For a sense of perspective, this is, as the report authors point out, nearly half the $2.5 trillion in total combined net worth held by the 65 million US household that form the poorest 50 percent of Americans.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Some of the key findings of the report are below.

- As the words “aristocracy” and “dynastic” suggest, the status of the wealthiest families is highly stable. If you looked at the list of 50 wealthiest families in the US in 1983 and compared that list to a similar one for 2020, more than half (27 of 50) of the families are the same. Only four of the wealthiest 20 families in 2020 are new to the list. Between 2015 and 2020, the only family to see its rank decline significantly was the opioid-pushing Sackler family.

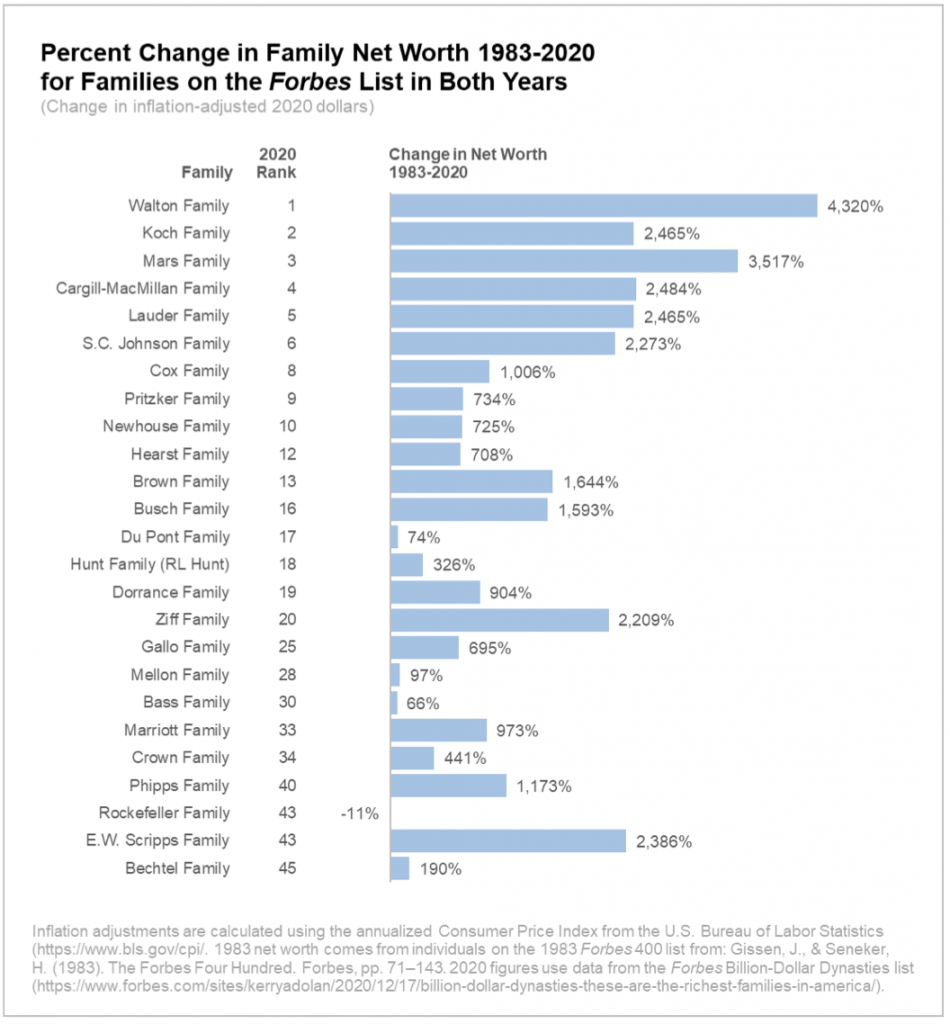

- The rich are getting richer—a lot richer. In and of itself, that outcome is no surprise, but the rapidity of these wealthy families’ rise might be. The top five families all saw their wealth increase by more than 2,000 percent. The gain in wealth is astonishing, but that is not a typo; each of what are now the top-five families have seen their inflation-adjusted wealth increase more than twentyfold since 1983. All told, a dozen of the 27 families that were on the top 50 list both in 1983 and 2020 saw more than a tenfold increase in wealth, and all but four at least doubled their wealth.

- A few dynastic families did less well than the rest. Three of the 27 families on both the 1983 and 2020 “top 50” lists saw their wealth increase by less than 100 percent (the Du Pont, Mellon, and Bass families), and one saw their wealth actually decline modestly, by 11 percent (the Rockefeller family).

- The Giving Pledge trend, common among tech billionaires, is rare among US multigenerational dynastic wealth families. Signers of the Giving Pledge—and over 200 billionaires have signed—pledge to give away half of all their assets. As has been pointed out in NPQ, many of the pledgers, despite their pledges, have seen their wealth rise. Even so, deeply flawed as the Giving Pledge is, at least it manifests an intention to share the wealth. Among the 50 dynastic families studied by IPS, however, only four have any members who have signed the pledge.

- There are many different generations of dynastic families that can be traced throughout US history. The earliest family groups, such as the Du Pont, Busch, and Cargill-MacMillan families, date from the early-to-mid 19th century. Later generations are also described in the report, divided into three main categories: the late 19th century, the early 20th century, and post-World War II. There will surely be a “tech generation” too, but that money was earned too recently to be classified as dynastic wealth yet.

Much of the report is dedicated to tracking the manifold efforts by dynastic families to shield their wealth from taxation. These strategies and tactics are not too surprising, but the six preferred tactics identified by the authors are to 1) oppose taxes on wealth; 2) limit the amount of charity; 3) form a “family office” to shield wealth and income from taxes; 4) use trusts to evade estate taxes; 5) use wealth to support public policy that protects wealth through lobbying, political action committees (PACs); and sometimes direct involvement in government commissions or even public office; and 6) leverage the charitable contributions that they do make to support think tanks or channel donor-advised fund (DAF) contributions to political effect.

More interesting is a section that outlines some people who purposefully opted out of creating dynastic wealth. As these examples show, multigenerational dynastic wealth is a choice. A famous example of a person who opted not to establish a family wealth dynasty was Andrew Carnegie, who, the authors note, gave away over his lifetime “an estimated $350 million, including $55 million to build over 2,500 libraries. And by the time he died in 1919, he had used the bulk of his fortune, $145 million, to endow five major philanthropic organizations including the Carnegie Corporation of New York and the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.” More contemporary examples include Chuck Feeney, who maintained a philosophy of “giving while living,” practiced it by giving away $8 billion through Atlantic Philanthropies, and now has a net worth of $5 million (less than one thousandth of his original wealth); and Craig Newmark of Craigslist, who opted not to exploit the obvious opportunity to amass billions in wealth by refusing to allow ads to run on his web-listing service.

Can Policy Stem the Rising Concentration of Dynastic Wealth?

Beyond relying on the goodwill and voluntary actions of a few unusual folks like Feeney, what can policy do to reduce concentrated wealth? The policies proposed in the report focus largely on taxation and legal enforcement. In terms of tax measures, proposals floated by the report authors include higher estate taxes, inheritance taxes (paid by the recipients of bequests rather than the estate), a wealth tax, a special “pandemic wealth tax” to reduce wealth accumulated during the COVID-19 pandemic, and a surcharge on the income taxes of millionaires. The report also calls for strengthening rules to limit the use of trusts to evade taxes and for stricter tax enforcement.

The report ends with a warning: “For the last four decades, we’ve witnessed a steady updraft of income and wealth to the richest 0.1 percent of households. The wealthiest families in the US are deploying their professional ‘wealth defense industry’ to sequester hundreds of billions in wealth and placing it into dynasty trusts and other vehicles beyond the reach of taxation and accountability.”

“If we remain on our current trajectory,” Collins and his team contend, “today’s individual billionaires will be tomorrow’s wealth dynasties. With over 700 US billionaires in 2021, up from 15 billionaires in 1983, this will lead to further concentrations and wealth and power.” A failure to check dynastic wealth, in short would pave the way for even greater billionaire dominance over politics, culture, the economy, and philanthropy.