Union leaders are scrambling to respond to a survey of black women in the labor movement, which showed that while the women represent one of the country's most unionized demographics, they remain underrepresented in union leadership.

Less than 3% of the respondents said they had held elected leadership positions, and nearly half said they felt there were structural barriers to their advancement. Only 27% said their union invests resources in organizing black women workers.

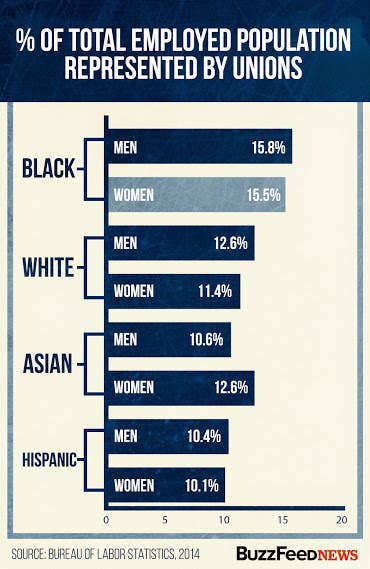

That's despite the relatively high unionization of black women, who come second only to black men in their membership of unions.

The study, released last week by the left-leaning Institute for Policy Studies, already has some of the country's biggest unions pledging to do more to get black women represented in their leadership — a pledge that dates back decades. In 1995 the AFL-CIO, the country's largest federation of trade unions, passed a resolution to increase the diversity of its leadership.

Almost 20 years later, that work is yet to be completed, the report said, but unions say they are on the case.

The United Steelworkers union now plans to have a coordinator in every local chapter for their women's leadership program "Women of Steel," and the Ohio chapter of the AFL-CIO plans to hire a staff member dedicated to the social issues the report shows to be especially important to women of color. Other members of the labor movement also said they're evaluating their programs for specifically training black women organizers, with an eye to expansion.

"The president of our union emailed the report to the entire executive board on Sunday," said Roxanne Brown, assistant legislative director for the 1.2 million member United Steelworkers. "He touted it as important not just for women of color, but for the labor movement as a whole."

The IPS study said that while the benefits of union membership for black women are well-documented — they earn, on average, $4 an hour more than nonunion peers — the benefits of black women in union-building have received less attention. The study surveyed 467 black women in the labor movement and noted that organizing women of color delivered election wins more reliably than any other demographic.

"If unions and the labor movement are to have a future, that future will not be male, pale, and stale," said Marc Bayard, one of the study's authors and director of the Black Worker Initiative at IPS.

The study was released in the wake of a series of protests that highlighted how two of the country's most vibrant protest movements — the minimum-wage-focused Fight for 15 and anti-police-brutality Black Lives Matter — are moving closer together. Activists from each were present in numbers at protests organized by the other, first at a national day of minimum wage protests on April 15, and then in the rallies held in response to the death of Freddie Gray in police custody in Baltimore in late April.

A "colorblind" approach to organizing black women workers misses the mark, the study said.

Only about 1 in 4 black women agreed with the statement, "The same skills and tactics for organizing white women workers will work with black women workers."

Specifically, the women surveyed identified caring about social issues including incarceration, criminalization, police brutality, fair scheduling, and access to child care — "issues we would not have seen as the traditional bread and butter issues of labor," said Kimberly Freeman Brown, one of the study's co-authors.

The American Federation of Teachers (AFT) has been acting on this trend, according to Dr. Lorretta Johnson, secretary-treasurer for the union. It has been reaching out to communities of color on issues of civic engagement and voter registration, she said, and has planned a series of town hall meetings on racial justice in the wake of events in Ferguson.

"You can't just be a part of a community when you need something. You have to be a part of a community when they need something," said Johnson.

This theme came through clearly in an interview between the ISP authors and Alicia Garza, special projects director for the National Domestic Workers Alliance (NDWA) and co-founder of the Black Lives Matter movement.

In Ferguson, she said, "I saw leaders from the Fight for 15 movement... moving labor leaders by saying, 'I'm not just a worker. I'm someone who lives in this community, who is being targeted by police all the time — and you have to see that about me.'"