Got $5 Million? Yale Will Manage It, But You Won’t Get It Back

Got $5 Million? Yale Will Manage It, But You Won’t Get It Back

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- In this charitable giving season, elite universities are cashing in on the popularity of donor-advised funds by inviting big givers to have their money managed by the same high-powered investors who oversee their endowments. If you have enough cash to give away, Yale, Stanford, Dartmouth, and other schools will look after it for you while you decide where to donate it. Of course, much of it eventually has to go to the college.

Donor-advised funds are investment funds for charitable donations. You deposit money, get a tax deduction, and use the presumably growing balance to fund charities of your choice over time. Donor-advised funds held $110 billion in 2017, compared with $57 billion in 2013, according to the National Philanthropic Trust, a donor-advised fund sponsor. Through their charitable arms, Fidelity, Charles Schwab, and Vanguard rank among the leading managers.

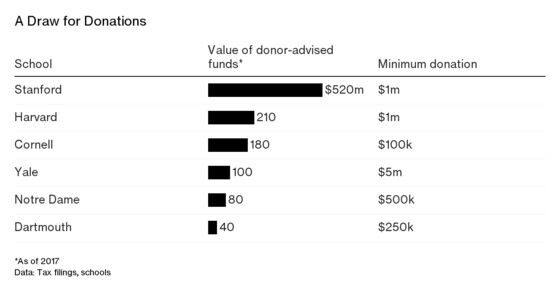

Dartmouth, Yale, Harvard, Stanford, and Notre Dame are among a dozen endowments that have gathered a total of $1.2 billion in endowment-managed donor-advised funds, according to a Bloomberg review of the 25 richest private colleges’ most recent tax filings. Stanford led the pack with more than $500 million, more than twice as much as No. 2 Harvard. They’re growing fast. Yale managed $100 million as of June 2017, almost triple the amount four years earlier. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, another top-performing endowment, is just starting one. Princeton is one of the holdouts; it says it hasn’t seen the demand.

University endowments have some competitive advantages as donor-advised fund managers. They already oversee half a trillion in investments. And endowments are famous for being able to make long-term investments a typical money manager can’t—in everything from venture capital to private equity to agricultural land. But only the wealthy need apply: Yale requires the biggest minimum investment, $5 million; Stanford, Harvard, and Columbia require $1 million; Cornell, a mere 100 grand.

“I get fantastic returns,” says Barbara Dau, Dartmouth class of 1978, who used her school’s fund to support the college’s Hopkins Center for the Arts and its Hood Museum of Art. “I don’t get to keep it personally, but I love that the account is growing, and the impact where I direct my gifts will be greater.’’

The rapid growth of all donor-advised funds worries some critics since it gives immediate tax breaks while allowing the giving to be deferred. A recent report by the Institute for Policy Studies, a Washington think tank, said they are potential “warehouses of assets for the wealthy.” Congress has already attacked universities for hoarding tax-free money in their endowments as tuition skyrockets.

Colleges say they have taken steps to address concerns about hoarding. Dartmouth, for example, requires that 5 percent of each fund be spent annually. “Our goal is to push it out—we don’t want to sit on it,’’ says Susan Hanifin, who directs planned giving.

The charitable arms of investment companies say that they, too, have mechanisms for making sure the money doesn’t sit idle. Fidelity’s charitable fund requires that donors make at least one gift within five years; otherwise it will close the account and Fidelity will distribute the money to charity. Vanguard moves 5 percent to charity if money isn’t spent within five years. Schwab has similar rules and says 80 percent of contributions make their way to charity within 10 years.

University-run donor-advised funds generally require that half the money end up benefiting the college itself. Donors are typically free to steer the rest of money into other charities of their choice. Colleges must approve distributions. Notre Dame won’t direct money to organizations such as Planned Parenthood that conflict with its Catholic values, according to university fundraising spokesman Gregory Dugard. The school says its donors prompted the opening of its charitable fund because they wanted to use the endowment’s high returns to benefit local parishes and other charities.

Despite the good intentions of charitable givers, some critics are still concerned about how donations tend to flow to already-wealthy institutions. “It’s part of this pattern, which is top-heavy philanthropy,” says Chuck Collins, an author of the Institute for Policy Studies report. “The winners tend to be the big institutions who can cater to and manage these big gifts.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: John Hechinger at jhechinger@bloomberg.net, Pat Regnier

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.