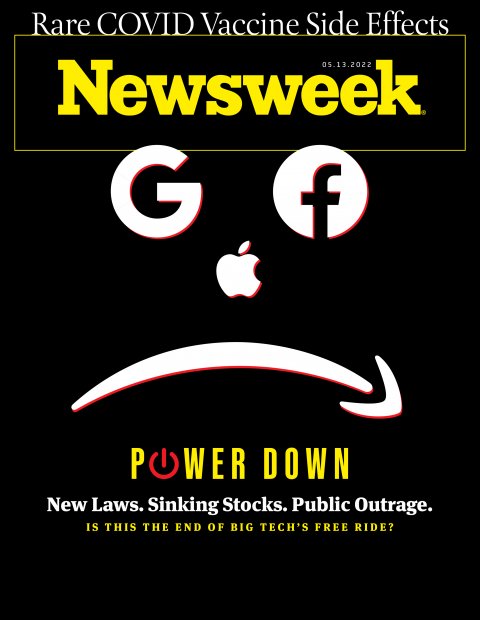

In February, the company formerly known as Facebook lost $232 billion in value in the stock market—the biggest loss ever suffered by a U.S. company in a single day, a plunge equal to the combined market values of Netflix and Fedex. By the end of April, the stock had lost another fifth of its value.

Meta Platforms, as the company is now formally known, can only wish that a brutal stock beating is its only problem. Meta faces serious threats on several fronts, and any one of them might prove existential. For the first time in its 18-year history, the number of people who use the once-ubiquitous-seeming Facebook social network has been dropping. Privacy protections added by Apple last year to its phone software are hobbling Facebook's bread-and-butter ad business, which depends on keeping tabs on what users are up to. And the all-important youth market is shunning Facebook in favor of TikTok.

Meta is also facing a daunting level of ire, which is splashing over onto the rest of Big Tech—that is, Google, Amazon, Apple and Microsoft. These tech giants and Meta are facing scrutiny from regulators and legislators both in the U.S. and Europe. And they are all objects of an intensifying resentment on the part of the public. A sign of the times: A Democratic Congressional candidate in Virginia, Andy Parker, was, until pulling out in mid-April, running almost entirely on a platform of curbing Big Tech's enabling of bad behavior online.

The governments of the U.S. and Europe have essentially decided that they don't want a handful of giant tech companies, accountable to no one but their shareholders, steering the actions of their citizens and shaping our collective worldviews, all in the service of amassing staggering wealth. Legislators and regulators on both sides of the Atlantic are now squaring off against the digital behemoths in what is shaping up to be a modern version of the massive 20th-century antitrust battles with Standard Oil and AT&T.

In late April, the European Union tripled down on its harsh, anti-Big-Tech regulation by passing the Digital Services Act, a suite of laws that would force the giant tech companies to police disinformation, illegal content and misleading advertising far more aggressively than they have in the past. In the U.S., regulators, attorneys general and members of Congress from both sides of the aisle are lining up to take action against Meta for its problems managing privacy, disinformation and censorship, as well as abusive and predatory online behavior.

Perhaps more than anything else, the sheer size, influence and wealth of these companies is raising concerns—and painting bullseyes on their backs. "There's a growing understanding that this concentration of power and enterprise is bad for the rest of us," says Chuck Collins, a senior scholar at the Institute for Policy Studies, a Washington, D.C., progressive think tank. "The pitchforks are coming for them."

If successful, efforts to curb the power of these firms will change the world as we know it. It will either mean reducing our dependence on the digital tools these companies have pioneered and largely offer for free, or open up competition to new tech companies that aren't so quick to invade privacy, transmit disinformation, spray advertising and support our worst behaviors.

The results will reverberate through our lives in ways no one can predict. The free services we have come to depend on to search out information, stay in touch with friends, navigate the streets, get goods zipped to our doorsteps and place everything from banking to ridesharing at our fingertips could become expensive, or less convenient—or might dry up altogether. Or perhaps, as happened with Standard Oil and AT&T, we will enter a golden age of competition that yields more choice, better products and lower costs while respecting privacy. .

Big Tech is facing a reckoning. It won't go down without a fight, but there may be little it can do to stem the backlash.

The Trillion-Dollar Club

Big Tech is raking it in, plain and simple. In 2021, while the world struggled with a surging pandemic, Meta, Google, Amazon, Apple and Microsoft—the Big Tech Five—enjoyed surging revenues. Combined they took in well over $1.2 trillion, the most they've ever made, and close to $200 billion more than in 2020, which was itself a record year.

Even Meta, despite all the battering its reputation and stock are taking, is sitting pretty. Last year it took in $86 billion. The recent drop in daily users is a blip compared to its total of two billion users a day. Its monthly user total, which is the metric more closely watched by advertisers, is still rising. "People are talking about Facebook as if it's about to become the next MySpace or Yahoo," says Daniel Salmon, an analyst who follows Meta for BMO Capital Markets, referring to two once-dominant tech companies that faded away to

insignificance. "But I don't think that's going to happen."

What's more, Meta's efforts to dominate the future of the nascent virtual-reality (VR) "metaverse"—where goggle-wearing users explore, game, learn, shop and meet up in 3-D spaces—are starting to bear fruit. Meta's Quest VR goggles have taken over about half the market; its Quest software store has hit $1 billion in sales since it debuted in 2020; and its online metaverse platform has grown by a factor of 10 over the past three months to 300,000 users.

Meta and the other members of the ultra-elite club of tech titans is gunning hard for even more dominance. They are spending hundreds of billions of dollars to add new facilities, expand product lines and buy smaller companies. These five tech giants alone account for nearly one out every 10 dollars invested by businesses in the U.S.

This success and ambition might be viewed more favorably if a significant portion of the enormous wealth these companies generate was passed along to workers in the form of high wages. But the windfalls tend to enrich a small cadre of investors and tech-savvy knowledge workers in Silicon Valley and Seattle rather than the factory workers churning out iPhones or those laboring in Amazon delivery vans and warehouses. It's no coincidence that the formidable Teamsters union is throwing its weight behind—and gaining ground in—an effort to unionize Amazon workers. On April 1, the Amazon facility in Staten Island, N.Y., became the first whose workers voted to do so. Union organizers say they're looking to increase hourly wages from about $16 to $30.

It might help, too, if the Big Tech Five continued as the bold disruptors of tired industries they once were. But lately they've congealed into what economists call "rent extractors," collecting a virtually assured continuous stream of money by offering only incremental improvements in their products. The iPhone and the Windows operating system once represented meteoric improvements in technology, but the iPhone 13 or Windows 11 are hardly distinguishable from their predecessors.

"The experiences they give us aren't all that great anymore," says Maritza Johnson, who heads the Center for Digital Civil Society at the University of San Diego. "It's harder to get excited about it."

What's becoming easier to get excited about, on the other hand, is how Big Tech—and, in particular, Facebook and Google—have converted what they know about their users into a massive income of advertising dollars. For years users seemed to give these incursions into online privacy little thought, but now concern is growing.

Meta, for instance, has been under fire for tracking what its users click on and see online. The company fields an array of data-gathering tools that reach across the entire web, including phones and other mobile devices. Through a vast network of business partnerships, Meta now receives data from more than eight million websites describing the activities of Facebook users who visit the sites. The sites and apps feeding Facebook's huge appetite for data include Yelp, Duolingo, Indeed and many others.

Although Facebook has seen serious competitors spring up, it acquired two of the biggest and fastest growing: Instagram and WhatsApp. The messaging app WhatsApp rose to popularity around the world in large part because it was considered a beacon of privacy protection, shrouding all its messages with encryption. When Meta bought the app's parent company in 2014, the company said it would keep those privacy protections. Early last year, however, it told WhatsApp users that they either had to consent to being tracked by Facebook, or delete the app. It relented only after millions of users fled the app for independent competitors like Signal. Meta is particularly thorough in gathering data from users of its own websites and apps. For instance, it hangs on to as much as 79 percent of the personal data it sees through its Instagram app, according to an analysis by information-technology-services company PCloud.

It's no secret that Meta uses that data to help advertisers hit up the right users with the right messages, as well as to shape its recommendations for content to look at and groups to join. Apple's 2021 iPhone privacy enhancements, which push users to choose whether they want to allow third parties to track them, put a crimp in Meta's data-gathering abilities. But the company still has a rich stream of information on users flowing in through Android phones and the web. It is also well positioned to turn the metaverse into a new, even larger pipeline of user data, largely because VR goggles like Meta's Quest include cameras that can observe the user's body and surroundings.

Facebook's data collection practices might not seem invasive when couched in anodyne business terms of browsing habits and advertising. But the information it routinely gathers on each one of its users would make a revealing dossier. Data on browsing habits—what web pages people visit, what they click on there, and what they buy—could easily reveal political views, health concerns, eating habits, travel plans and social circles. There's no telling what else clever artificial-intelligence programs could glean from each person's digital habits in the future. Considering that Facebook collects this data on the digital activities of millions of people 24 hours a day, seven days a week, it starts to look like a potential privacy nightmare on a vast scale.

Exactly what data Facebook is enlisting, and in what ways, is very much a secret. "It's so opaque that people don't even know exactly what questions to ask," says the University of San Diego's Johnson. "And if they did, Facebook wouldn't answer, and if Facebook did answer there'd be no way to verify the answer."

As if to underscore the point, Facebook declined to make an executive available for an interview for this article.

Cracking Down

Google, too, collects enormous streams of data about people and shares it with advertisers. Much of it comes from the keywords we type into searches, but it also gathers information about users through the websites they visit and what they click on there, largely thanks to its ownership of the Chrome browser used by two out of three website visitors. Google's voice assistant and home services, such as speakers, security cameras and smoke alarms, provide another source of insight into user behaviors. And Google owns Android, the phone operating system that's on more than twice as many phones as Apple's iOS, offering another major way to know what users are doing. (Google, too, declined to make an executive available for an interview.)

Apple has access to similar sorts of user information through its own hardware, software and services, but now offers protection from third-party tracking by default. Meta and Google both offer users the option to set similar sorts of tracking-protection features, but users typically don't take the trouble or don't have the know-how to find and activate these protections. Also concerning: All three mega-companies have invested heavily in artificial intelligence, which can figure out much more about a person from a given set of data—inferring that someone is likely to have a particular health problem, for example, or a certain sexual preference, based on patterns in online behavior.

The public seems fed up with being tracked by the tech giants. An October survey conducted by the Public Affairs Council and Morning Consult found that Americans rank the tech sector near the bottom of all major business sectors in trustworthiness; only the pharmaceutical, health insurance and energy industries earned less trust. That's a huge shift from just four years ago, when the same poll found that the tech industry was deemed the most trustworthy. Surveys from four or more years ago suggested that many users were once willing to trade off some privacy for the convenience of online services and platforms, but the newer data suggests that deal is looking increasingly unattractive.

Perhaps even more aggravating to many people than the potential privacy violations, at least where Meta is concerned, is the tension between the spread of hateful, predatory and dangerous misinformation and efforts to remove or limit toxic posts and comments. Starting with Facebook's role in promoting election disinformation in 2016, liberal critics lambasted the company for its failure to police its platform against false claims about election fraud, anti-vaccine propaganda and calls for political violence preceding the January 6, 2021, insurrection. But Facebook's business model is crucially dependent on algorithms that promote posts that are likely to appeal to a user—a practice that tends to push the most inflammatory and inaccurate material to the top.

Adding further fuel to the fire, Meta former-employee-turned-whistle-blower Frances Haugen disclosed a trove of damaging inside information about the company's failure to control problematic content in 2021 Congressional testimony. In particular, she revealed that the company had suppressed the findings of its own research showing that Meta-owned Instagram was harming teens' mental health. The revelations made it clear that Meta's own software wasn't merely failing to catch and remove the most dangerous and toxic content, it tended to actively promote it.

"The most polarizing things are the ones being promoted," says Janna Greenberg, a communications researcher at Boston University. "Neo-Nazis had never had a voice before."

Conservatives, on the other hand, have railed against various efforts on the part of Meta, Google and other tech companies to remove election-fraud, anti-vax and other disinformation that tends to resonate with large parts of their followers. "Facebook gets attacked from the left for not taking down enough and from the right for taking down too much," says Rob Atkinson, president of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, a nonprofit technology policy think tank in Washington, D.C., that receives some of its funding from technology companies. "It can't win."

But politicians and regulators can win, by catering to the widespread ire against Big Tech with punitive actions. A November Washington Post-Schar School poll found that two in three Americans say the government needs to take action against these companies.

The resulting array of legislation and lawsuits being proposed is breathtaking. The House of Representatives is considering the Justice Against Malicious Algorithms Act along with the Protecting Americans from Dangerous Algorithms Act, either of which would remove the protection known as Section 230, which shields social media companies from liability for what their users post. And the Filter Bubble Transparency Act, introduced by a bipartisan group in the House, with a Senate version submitted by Republicans, would require Meta, Google and other large social-media companies to either get rid of the algorithms that promote content or offer a second version of their network that doesn't enlist the algorithms.

In the Senate, meanwhile, the bipartisan Social Media NUDGE Act would enlist the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine and the National Science Foundation to come up with techniques that Meta and other social-media companies would be forced to use to tame harmful content online. And the Senate is also looking at a Kids Internet Design and Safety (KIDS) Act that would require the companies to offer special protection for minors. All of these proposed bills are currently in committee, and while it's difficult to predict when any or all of them might make it to the full chambers, the bipartisan backing they are receiving suggests they all have a good chance of becoming law in some form.

The states are also moving on new laws. In July, Colorado joined California and Virginia in passing legislation that broadly protects residents' online privacy rights, including giving them the right to know about and delete all tracked information, and to opt out of future tracking. Similar bills are being actively considered by legislatures in 12 other states, including Alaska, New York, Louisiana and Pennsylvania. The growing legislative onslaught simply reflects the public's increasing concerns about privacy, says BMO analyst Salmon. "People like getting all these free services from tech companies," he says. "But they don't want the companies collecting their data."

Even without new laws, Big Tech is likely to be hit with more and more fines for its perceived transgressions. Both the Justice Department and the Federal Trade Commission, which fined Facebook $5 billion in 2019 for privacy violations such as sharing users' data with third parties without their knowledge or permission, have announced they are closely looking at Big Tech's past acquisitions to determine if there is a pattern of anti-competitive behavior. And the FTC is also investigating Meta's VR business to determine if the company has priced its VR headsets and shut out third-party VR software developers in ways that violate antitrust law, according to reports from Bloomberg and others. State attorneys general are also expected to act; Texas has already sued Meta for illegally gathering facial recognition data from users, a case that's currently in discovery.

And private groups are getting in on the action: in February Meta settled a class-action suit over tracking users through cookies after they had signed out of the Facebook platform, agreeing to pay $90 million to plaintiffs. And an Illinois group is suing Meta over the practice of allowing the posting of photographs of people who aren't users of the company's platforms.

Break Them Up?

For all the recent action aimed at Big-Tech, the U.S. is playing catch-up with Europe. The European Union passed the General Data Protection Regulation, or GDPR, back in 2018, placing strong limits on how tech companies can collect and use data, such as limiting user data to the minimum needed for an approved purpose, protecting the confidentiality of the data, and ensuring the data is accurate and up-to-date. That regulation even limits the ability of Big Tech to move data across borders to countries such as the U.S., where using the data would be legal.

Meta and Google have both publicly complained that the laws are hurting their core businesses. In filings with European regulators, Meta has implied it might withdraw access to its platforms from European users—though the company later issued a statement denying it is "threatening to leave Europe."

In March, the E.U. doubled down on its efforts to constrain Big Tech's growth by passing the Digital Markets Act, which places severe new limits on the companies' ability to promote their own products over competitors', to keep competitors from accessing their services, or to bundle or pre-install their services—all practices that are key parts of these companies' strategies. Under this act, for example, Google might not be able to pre-install its Android software on some phones or promote its own services in search results, Meta might not able to combine the data it has on Facebook and Instagram users, and Amazon might not be able to keep competitors from accessing information about the nearly two million merchants that sell on its platform.

European regulators have already leveled a nearly $3 billion fine on Google for promoting its shopping-comparison service over those of its competitors. Italy and the Netherlands have hit Apple with multi-million-dollar fines for anti-competitive behavior. And the U.K., which has already forced Meta to sell one small competitor it acquired, has appointed a special regulator to keep a particularly close eye on both Meta and Google.

The Digital Services Act goes even further. It would force the giant tech companies to police disinformation, illegal content and misleading advertising far more aggressively than they have in the past. The law, which bans online ads aimed at children, authorizes the European Union to levy fines of six percent of a company's annual worldwide revenue and to banish recidivists from the EU entirely.

The U.S. seems ready to follow Europe in cracking down. FTC Chair Lina Khan, appointed in June, has in the past proposed prohibiting Big Tech companies from expanding through antitrust regulation. One FTC antitrust suit against Meta, based in part on its acquisitions of WhatsApp and Instagram, got a green light from a judge in January. Separately, the FTC, along with several states, is investigating Meta for anti-competitive tactics in its new VR and metaverse business.

Google, meanwhile, faces lawsuits from the U.S. Department of Justice and multiple states over its dominance of the online search business. Congress is also considering two bipartisan bills, the American Innovation and Choice Online Act and the Open App Markets Act, that would further limit Big Tech's ability to stifle competition. Both are advancing to the Senate floor, where they are likely to pass.

Wielding antitrust law against Big Tech is tricky, says the Institute for Policy Studies' Collins, but growing public resentment of the companies have spurred lawmakers and regulators to figure out how to do it. "Anti-trust is a blunt instrument that was meant to address pricing competition, which is why it hasn't been used in meaningful ways in years," he says. "But the new actions are about the larger issues of bigness, power and influence."

When it comes to cutting Big Tech down to size, the history of antitrust in theU.S. suggests that the free market may beat regulators to the punch. The last big antitrust actions, against Microsoft in 1998 and IBM in 1969, were essentially dropped because competitors rose up to challenge and eventually beat the companies at their own game. Today IBM is a relatively small player, and while Microsoft is still a giant, its market value is half a trillion dollars less than Apple's. Today's Big Tech Five might likewise give up ground to smaller, nimbler, more innovative competitors.

Or it may be that they take each other down, like battling kaijus, as they start going after the same markets. Meta is now in the hardware business via its Quest VR headsets, where it competes directly with Google, Apple and Microsoft, who have been trying to get into this potentially explosive area. Amazon has seen Meta's Facebook Shops platform, as well as shopping on Instagram, cut into its core business.

What's more, Apple's move to block iPhone apps from tracking users by default may be just the first salvo in a war between Apple, Meta and Google to limit each other's insights into their users, damaging all their businesses, and perhaps dragging down the entire online advertising industry. Even Amazon and Microsoft could be hurt—they each earned $31 billion and $10 billion from advertising in 2021, respectively, and both clearly intend to grow those numbers. The proportion of the Big Five's revenues that come from businesses in which they compete with each other is now 40 percent, twice what it was six years ago, according to The Economist.

"A lot of the effort to undermine these companies is coming not from the public, but from competitors," says the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation's Atkinson. "Some of the biggest attacks are between the big tech companies themselves."

You'll Miss Me When I'm Gone

Regardless of whether Big Tech succumbs to regulators, its own internal combat or new competitors, the public is likely to be the ultimate winner, claims Johnson. "Right now, it's hard to argue that consumers have a real choice," she says. "But I think that's changing, and we can be hopeful that a new wave of innovations is coming."

If this indeed is the beginning of the end of Big Tech, will we one day come to miss it? Will we look back nostalgically at Google's search bar, Facebook's news feed and Amazon's one-stop marketplace and the feeling of being enveloped in low-cost, convenient services? Or will we revel in the freedom and innovation that a new generation of scrappier, less-invasive companies brings us?

We should know soon enough.