Walking into a restaurant in Washington, D.C. these days means entering a battleground. The city’s dining establishments are the current front in a war over the subminimum tipped wage — the lower base wage that employers pay tipped workers. On June 19, D.C. voters must decide whether or not to join seven other states that require those employers to pay their tipped employees a full minimum wage.

Initiative 77, and the heated debate around it, has dragged a long-standing national discussion over the subminimum tipped wage into the light. On one side is One Fair Wage, which is in favor of the proposal to gradually raise tipped base pay until it’s in line with the standard minimum wage by 2026.

The opposition, which has raked in funding from the restaurant industry, has branded itself as “Save Our Tips.” While the ballot initiative has no language that would change tipping practices, the anti-77 campaign is pushing to maintain the status quo of D.C.’s $3.33 subminimum tipped wage plus tips.

For Kelsey, the scant hourly pay became an issue when she moved to the nation’s capital. Kelsey — whose name, along with those of all the other tipped workers interviewed for this piece, has been changed to prevent retaliation on the job — works for Clyde’s Restaurant Group. She’s been in the service industry for nearly two decades, but hadn’t heard of the subminimum tipped wage until she began training at her current job. There’s no discrepancy in the minimum wage for tipped workers in her home state of California.

“I would know that there’s a stable paycheck that I could count on every two weeks. That there would be some sort of consistency in my life that doesn’t have to depend on whether it was a good night or a bad night, which regulars came in versus who didn’t,” she says. Anti-77 workers in D.C. worry that their tips will dry up if the initiative passes. But in Kelsey’s experience, her tips were no different with the higher base pay. “I know that it works in California, and people are shell-shocked when I tell them that.”

Research shows it works elsewhere, too. Initiative opponents say that increasing the minimum wage would force businesses to close their doors, leading to fewer jobs. But a recent policy brief from the Institute for Policy Studies and Restaurant Opportunities Center United, the worker group advocating for Initiative 77, found that to be untrue.

The researchers studied a New York county that raised its tipped wage from $5 to $7.50. Workers’ take-home pay went up, as did the number of restaurant jobs. Meanwhile, a neighboring Pennsylvania county with the same economic indicators — besides a tipped minimum wage of $2.83 — saw a smaller pay increase as well as a decline in jobs.

Kelsey has been surprised at how controversial Initiative 77 is among her colleagues, many of whom she says seem to be misinformed on the proposal and its consequences. She suspects this is due to a well-funded PR blitz from the Save Our Tips campaign that’s taken over her workplace. “This is ground zero. It’s really frustrating.” Workers at the restaurant wear pins to mark their opposition to the initiative, and servers are encouraged by management to engage with diners on the issue. The restaurant, like many in D.C., is covered in “Save Our Tips” signs.

The heated atmosphere in their workplace makes it difficult to speak openly. Kelsey says the restaurant is far more able to share its point of view with employees, especially as managers make use of required daily meetings and email bulletins to spread their rhetoric. She doesn’t have those resources, making it difficult to contrast her experience in California with the apocalyptic scenarios laid out by the anti-77 campaign. Besides, she’s worried about retaliation at work. “I really depend on my income from this job,” she says. “I have been very undercover with who I talk to and very fearful for my job.”

Her colleague Jane has also noticed heightened tension at the restaurant. Casual conversations turn into arguments. She recalls one particular exchange about the initiative with fellow servers, held in plain sight of the restaurant’s diners. When things became strained, a manager stepped in — not to calm nerves or to put an end to the discussion, but to try to convince Jane she was in the wrong about Initiative 77.

Jane has also seen a difference in the way her supervisor treats her, and she’s sure it’s because she ask questions when managers mention the initiative. Jane hasn’t told coworkers which way she’s voting. She’s only advocated for them to do their own research. “It was simply that management was pushing the politics on us in our workplace and not giving anyone the appropriate knowledge.”

Both Kelsey and Jane say they’ve heard heaps of rumors and fear-mongering among their colleagues. There’s been talk of the restaurant moving to a service charge model, Jane says, where the restaurant would add a fee to each bill to cover labor costs.

But Kelsey’s skeptical, and thinks the proposition has been put out there to encourage staff to vote against the initiative by threatening them with the potential loss of tips. Both workers say the restaurant is constantly in need of waitstaff, and the city’s in the midst of a restaurant staffing crisis. Unless all the other restaurants in the district adopted a similar measure, they don’t see how the group could move forward with the threat.

While the anti-Initiative 77 chorus is loud, Kelsey says she doesn’t think their viewpoint is typical of her colleagues in the district. “They don’t really represent, in my view, the tipped workers that I know who are informed about this topic. They’re not our voices and they don’t speak for us.”

TJ, a server and bartender at another restaurant in the district, is in a completely different situation. She imagines her restaurant is one of the few that has kept the workplace free of any conversations around Initiative 77, though she knows the restaurant owner is a vocal opponent.

Like Kelsey, TJ has organized with Restaurant Opportunities Centers United in favor of Initiative 77. She’s happy with her current workplace for being “one of the only employers I’ve worked for that has made it a point to make sure to follow the letter of the law as far as compensation goes,” she says. But she says that’s not standard in her industry, and she still wants the security of a basic minimum wage.

The consistency would have been helpful when she shattered her elbow last year, leaving her out of work for more than two months. “Because of the way my current wage system is set up, I’m not able to save,” she says. “There’s no stability.”

That economic anxiety is a basic fact of life for tipped restaurant workers, TJ says. “Every single person in this industry has been in the position where they haven’t made enough money.” Many anti-77 workers say there’s no need to increase tipped wages because they can bring in hundreds of dollars a night under the current system. There might be bartenders making that much, TJ says, but “they are working in high-end, high-volume, high-service establishments.”

Numbers from the Bureau of Labor Statistics back her up. It’s possible to make more than $30 a night as a server in the city, as the data shows the top 10 percent of waiters and waitresses do. But the median hourly wage for the district’s servers in May of 2017 was $11.86 — just 36 cents above the minimum wage at the time, and an indicator of the deep inequality within D.C.’s restaurant scene.

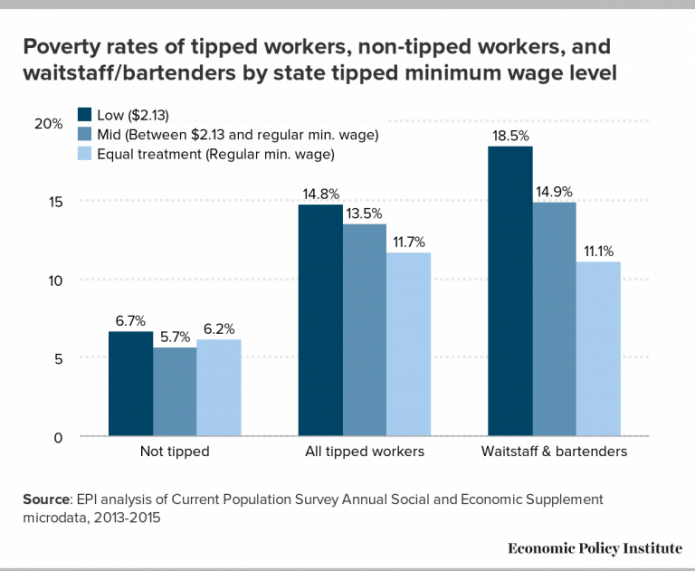

Besides, as a 2016 ROC United report found, tipped workers in the nation’s capital are nearly twice as likely to experience poverty in comparison to other D.C. workers. “The people who are serving you food can’t even afford to feed themselves,” says TJ. Initiative 77 could make real inroads on this issue. As research from the Economic Policy Institute shows, tipped workers have lower poverty rates in states without a subminimum tipped wage.

Economic Policy Institute

Anti-77 advocates often point out that tipped workers are entitled to receive at least the prevailing minimum wage, and employers must make up the difference if tips fall short, making the whole initiative unnecessary. But restaurant industry is rife with wage theft. TJ has struggled with the issue in the past — it’s why she became involved with the Restaurant Opportunities Center in the first place. Fortunately, she’d kept meticulous records which made it easier for her to recover her money. “The onus is on the employee,” she points out “to make sure they’re getting paid.”

Restaurant workers across the country understand this all too well. As the Economic Policy Institute reports, a Department of Labor compliance sweep from 2010 to 2012 found that 84 percent of restaurants had some type of wage or hour violation. This included nearly 1,200 misuses of the tip credit, which amounted to $5.5 million in back wages recovered for workers.

These numbers raise questions about the business model as a whole. “It’s like the biggest scam,” TJ says of the tip credit that allows employers to pay a subminimum wage. She finds it especially frustrating since some of the initiative’s most vocal opponents are also among the city’s most prominent and profitable restaurateurs.

Five D.C. establishments were among the top 100 highest-grossing restaurants across the United States last year. The restaurant groups behind all five also donated large sums in hopes of defeating Initiative 77. Among them are D.C. institutions Founding Farmers, Le Diplomate, and Joe’s Stone Crab, whose parent companies shelled out at least $5,000, $10,000, and $20,000 respectively to the Save Our Tips campaign. While Save Our Tips makes use of progressive rhetoric, jumping on the #DumpTrumpbandwagon on Twitter, The Intercept recently reported that the campaign was employing Lincoln Strategy Group, a consulting firm that provided services to Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign.

Two Clyde’s Restaurant Group outfits, Old Ebbitt Grill and The Hamilton, are also among the top 20 highest-grossing spots nationwide. The group has donated $15,000 to the anti-Initiative 77 campaign.

Jane finds it frustrating that the restaurant has bandied about the idea of switching to a service charge model when they’re able to absorb the cost of a pay raise. “Clyde’s can take this. It is not a big deal. Do you know how much money Clyde’s gives away and throws away on a regular basis?”

Customers have made disparaging remarks to servers, Jane says, only to have managers comp a meal or hand them a gift card to brush off the situation. “That’s especially disheartening because, one, the managers don’t have our back, but two, you can’t pay us minimum wage but you can pay these people to disrespect us?”

Much of the Clyde’s Restaurant Group service support staff is paid through tip pooling arrangements as well. Bussers and barbacks are tipped out at her restaurant, Jane says, and she also pays a daily service fee each day she works to cover the cost of cleaning glassware. “That whole front of the house, we pay them. And they don’t pay their back waiters, we pay them. And they don’t pay us!”

According to Jane and Kelsey, those front-of-house support staff aren’t generally part of restaurant-wide conversations around Initiative 77, even though they’re some of the workers most vulnerable to wage theft and poverty. “These are the people who allow me to make the tips that I make,” Kelsey says. “These are the people who allow [no on 77 workers] to make the tips that they make. And they’re putting a living wage out of their reach.”

For TJ, this is at the heart of the initiative — making sure all tipped workers, not just the bartenders at D.C.’s swankiest restaurants, have economic security. “It’s these people who are doing the most backbreaking work, the most unglamorous work,” she says of the tipped support staff, “who are making the least amount of money.” Restaurant owners need to see all of their tipped workers as crucial to the operation of the business, she says, and to pay them accordingly.

“You’re saying to us that you don’t have enough to pay your tipped staffers? That doesn’t make sense because we enrich you. We directly help the bottom line of your restaurants, and we work hard.”