Shutterstock

In every community, there are nonprofit charities that serve real needs: local food pantries, programs addressing the opioid crisis, the Red Cross chapters that come to our aid after a storm. Charities provide vital services to the people and places they serve.

These organizations lean heavily on volunteers, fundraisers, and donors. And most ordinary donors give without consideration of a tax break — people give their time, treasure, and talent without keeping score.

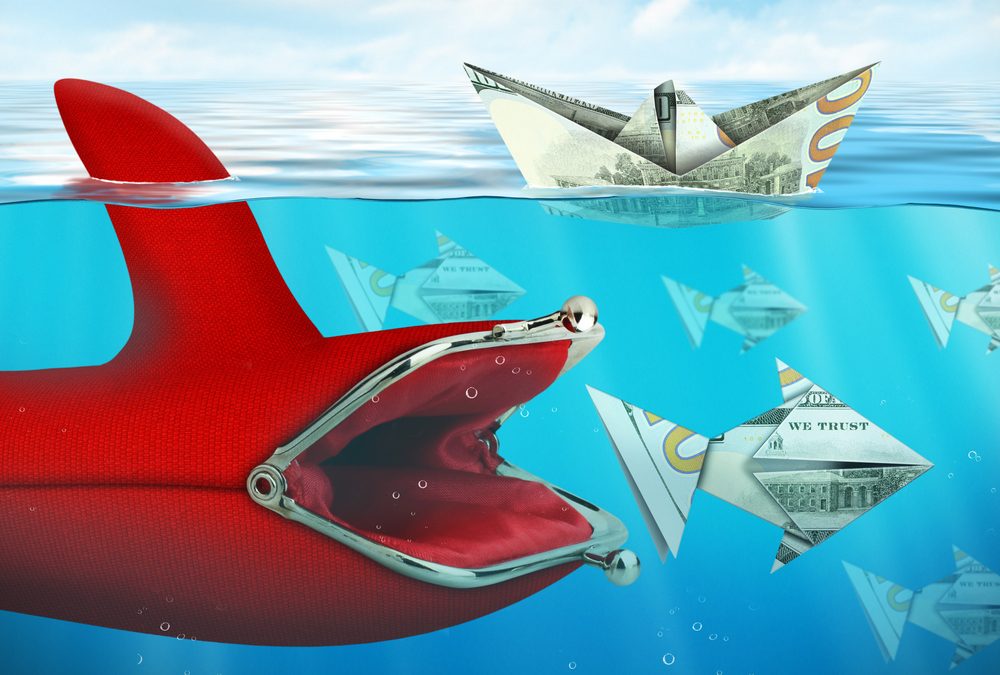

For many ultra-wealthy donors, however, charity can be motivated not just by generosity, but also by tax avoidance.

A case in point is the surge of donor-advised funds, or DAFs, created in recent years by wealthy donors. We studied these accounts in Warehousing Wealth, a new report for the Institute for Policy Studies.

A DAF is like a mini-foundation, a holding account for giving — but with substantially greater benefits and conveniences for the donors.

When donors contribute to a DAF, they take a tax deduction — often a big one. But those funds can then sit in the DAF for years, even generations, before they’re granted out to charities working to meet real social needs.

Originally created by community foundations, DAFs have been recently adopted by for-profit Wall Street firms like Fidelity Investments, Goldman Sachs, and Charles Schwab.

These firms created charitable DAFs to serve their wealthy clients’ philanthropic goals, while happily charging fees to keep funds under management. They have no legal incentive to see funds move in a timely way to active charities, so corporate-affiliated DAFs have been growing exponentially in recent years.

A decade ago, the biggest donation recipients in the United States were the United Way, the Red Cross, and the American Cancer Society. Today, it’s the Fidelity Charitable Gift Fund. In fact, six of the ten largest charity recipients are DAFs.

Donations to DAFs grew by 66 percent over the past five years, compared to just 15 percent for charitable giving by individual donors. Donations to Fidelity Charitable grew over 400 percent over seven years, to nearly $7 billion last year.

Our tax code provides incentives for people to give to charity through the charitable tax deduction. The ultra-wealthy are the biggest beneficiaries of this deduction, which comes at a cost to the rest of us.

For every dollar a millionaire gives to charity, the public subsidizes 37 to 57 cents of that donation through diminished tax revenue. By giving to their own selected charities, millionaires are paying less for public services like infrastructure, national defense, veteran care, and parks.

So there’s a natural public interest in making sure DAF donations at least move quickly to active charities. But there’s no legal requirement for DAFs to pay out quickly — or ever.

DAFs also open up loopholes for donors and private foundations to get around tax restrictions, and have little transparency and accountability.

Simple reforms could prevent these abuses.

Lawmakers could require the distribution of DAF donations within a fixed number of years. They could delay the tax deduction until funds are paid out to a public charity.

They could also ban DAFs from giving to private foundations, and vice versa — closing loopholes that further delay giving to active charities. And they could bring greater scrutiny to gifts of appreciated assets.

We don’t want to discourage charitable giving, but the current system poses significant risks to nonprofits, the people they serve, and taxpayers. As a society, we can’t condone hoarding wealth at a time of urgent social needs.