President Manuel Zelaya and his opponents now in charge in Honduras remain in a standoff. Inside the country, supporters of both sides are waging mass protests, while concerns continue regarding media censorship. This crisis provides an opportunity to look more closely at the Honduran political system and how it “broke.” Even more importantly, it’s a chance to consider what life is like for the average Honduran and how the United States impacts that small Central American country.

It’s somewhat ironic that Zelaya now bills himself as a “man of the people.” It’s even odder that he’s accused of being a “leftist.” In fact, he’s the son of a wealthy rancher once accused of killing leftist leaders, whose bodies were found hidden on the family ranch. Before running for president, Zelaya’s priorities in politics were mainly decentralizing government and protecting forestry against foreign concessions. If history tells us anything, his turn toward a more populist brand of politics has more to do with the energy of reform movements within Honduras itself, as well as throughout the rest of Latin America, than any personal awakening.

From the shift to civilian rule in 1982 until Zelaya’s ouster in June, the Honduran government appeared to be relatively stable. The country’s two major political parties, the moderate Liberal Party (of which Zelaya is a member) and the more conservative National Party, have virtually controlled political affairs. Traditionally, both represented social and economic elites who settled on trading off the presidency. The pact between the two parties included a mutual stake in the practice of favoritism, government secrecy, and the protection of military officers accused of human rights abuses.

Liberal Party Rift

A few years ago, however, the Liberal Party began to splinter as new voter groups entered the political system. These new members began to fight corruption, aiming to make government more transparent while trying to raise wages and living conditions for the poor. They also tried to bring the police and military to account for human rights violations. The growing divisions within the Liberal Party ultimately led to a breakdown of the two-party consensus.

As the economy worsened, Zelaya couldn’t ignore the party’s newer members and their agenda. Rising fuel and food costs, high unemployment, and increasing poverty led him to increase the minimum wage, subsidize food and, most critically, accept subsidized Venezuelan oil. With this, Zelaya drove a fateful wedge between the traditional members and the newer populist members of his party, prompting Liberal Party elites to ally with the National Party in a plan to oust him.

Corruption Ramps Up

At the same time, Zelaya continued a longstanding tradition of secrecy and corruption at the highest levels of government. This tradition was starkly revealed in the aftermath of Hurricane Mitch in 1998 — well before Zelaya’s term in office. The hurricane, one of the most powerful to strike in the Atlantic basin, killed about 6,000 Hondurans and left 1.5 million (roughly a fifth of the country’s population) homeless. The hurricane caused massive crop damage, decimated livestock, and largely obliterated the country’s infrastructure. The resulting lack of sanitation led to outbreaks of malaria, cholera, and other diseases.

As international aid rolled in, the Honduran congress soon turned over control of these funds and gave then-President Carlos Flores “permission” to forego the bidding process in approving contracts. While lawmakers delayed a scheduled increase in the minimum wage, Flores’ close associates benefitted from contracts for rebuilding roads, bridges, and other infrastructure. These associates included Roberto Micheletti, who now claims to be “president” of Honduras. In addition, the constitution was amended to allow foreign investors greater access to forested lands in coastal and border areas, a move that indigenous and Afro-Honduran communities living in these areas vigorously opposed.

Zelaya embraced the issue of transparency when he took office in 2006, boldly touting a law to give the public access to government documents and other sources of information. Until then, the popular bill hadn’t cleared Congress. Contrary to its purpose, the resulting law actually prevented declassification and public access to critical documents. This was achieved by allowing any minister to place any document into “reserved” status. Activists soon found that virtually all documents pertaining to humanitarian aid had been declared “reserved.” Still other reserved documents have pertained to security, privatization and governability. And while 10 years must pass before a document can be declassified, the purging of documents can be done every five years.

The question of financial corruption came up once again among international observers in 2007. This time, funds in question came from the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), a U.S. government agency whose goal is to reduce global poverty by targeting very poor nations for relief. This aid is contingent upon a government’s compliance with prescribed standards of transparency and, of course, the provision of a favorable investment climate. Honduras was one of a select number of countries to participate in the MCC early on.

Honduras didn’t measure up to the transparency standard, however. Never strong in this regard, the country had slipped several places in standard corruption indices. Since taking power, Zelaya’s administration had faced more than 20 accusations of corruption, including irregularities in the provision of healthcare supplies as well as contract awards, a longtime favorite of government leaders. In addition, Honduras’ own National Anti-Corruption Council had documented 3,000 cases of corruption going back to 2001. Out of these, only 11 had ever made it to court. Further, the country’s Social Forum on External Debt and Development reported that Honduras lost 38 million lempiras, or about $2 million a day, as a result of corruption.

Despite these findings, however, Honduras was permitted to continue in the program.

Human Rights Abuses

Another longstanding concern in Honduras has been the reports of extrajudicial killing of street children and young adults as a result of the government’s anti-crime program. Upon taking office in 1998, Flores initiated this program by unleashing a joint military-police force into the neighborhoods. In a country where murder, kidnapping, and other violent crimes had become routine expectations, many welcomed the program.

In its 2001 report, however, the Honduran Committee for the Defense of Human Rights held that “death squads” organized by the police had been responsible for the murder of 1,300 street children since the program had begun. The majority of those murdered were teenagers suspected of belonging to gangs, while the murderers were typically hit-men hired by private security agencies. The army owns many of these security agencies and uses them to fill the ranks of vigilante subdivisions under its own authority. Upon taking office, Zelaya vowed he would continue this offensive, targeting especially slums and poorer areas.

That year Casa Alianza, a program for sheltering homeless children, reported over 3,000 deaths of children and teens over a six-year period. Only 158 of these cases, however, had been investigated. According to the president’s Unit of Crimes against Minors, police officers had committed the murders in half of all cases, while privately hired hit-men were responsible for the rest. Some time after the report was filed, Zelaya — the “reformer” — closed down the Unit of Crimes against Minors.

Equally distressing is the apparent ineffectiveness of the government’s anti-crime program. Honduras continues to have one of the highest per capital murder rates in the world and gang related activity remains pervasive.

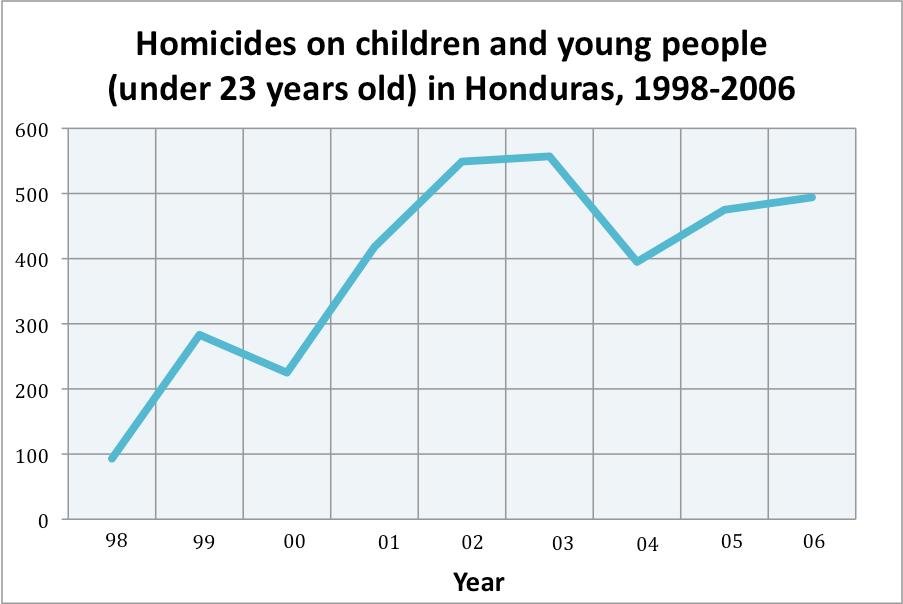

Source: Casa Alianza cited in Heidrun Zinecker, “Violence in a Homeostatic System – the Case of Honduras,” PRIF Reports No. 83, Peace Research Institute Frankfurt (PRIF) 2008; http://www.hsfk.de/downloads/prif83.pdf

The graph above shows the number of homicide victims from 1998-2006 who were less than 23 years of age. Over this period of time, the homicide rate for this population rose by over 500%.

U.S. Role

As Honduras’ foremost ally, the United States is in a unique position to monitor political openness and accountability in that country. U.S. and Honduran armed forces regularly carry out joint exercises that involve meetings between U.S. Department of Defense officials and the Honduran president.

In January, the U.S. military’s Southern Command “reaffirmed the United States’ strategic partnership with Honduras” and praised “the solid bilateral and interagency cooperation that is delivering tangible success.” In addition, Navy Admiral James Stavridis commented on the “tremendous progress” that had been made within the Honduran military due to the “emphasis on excellence, integrity and professionalism with the ranks, coupled with a close military-to-military relationship with the United States.”

Similarly, U.S. Air Force Major Tiffany Morgan commented on the show of professionalism by her other “brothers in arms” within the Honduran military in April of last year.

No mention seems to have been made of the evident corruption or reports of human rights abuses. Over time, the steady stream of U.S. military assistance has continued to flow, as indicated in the graph below. Here we see a twelve-fold increase between the 1996 total and the projected figure for 2010:

![]()

Source: The Center for International Policy’s Just the Facts. http://www.ciponline.org/facts/ho.htm, accessed 7/17/09

As the graph shows, military assistance spiked in 1999 following Hurricane Mitch, in 2004 with Honduras’ cooperation with U.S. policy in Iraq, and again in 2007 after the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA) went into effect.

Even more interesting was the U.S. State Department’s statement of congratulations to Hondurans last December, on the “clean and transparent manner” in which their recent primary elections had been carried out. “We particularly note the work done by the Supreme Electoral Tribunal and the Honduran military, which was responsible for protecting and delivering electoral materials.”

No mention was made of the four primary candidates who had been assassinated by masked hit-men in the weeks prior to the elections.

Since Zelaya’s ouster, a largely fruitless debate has emerged around who should prevail — Zelaya and his left-leaning agenda, or the right-wing opposition now in charge. Painfully little has been said of the abysmal conditions with which the average Honduran now lives: persistent poverty, a culture of violence, an unaccountable military, and pervasive corruption at virtually all levels of government.

Despite these conditions, military and economic goals have consistently taken precedence over the goal of good government. With regard to U.S. military goals, the Honduran military has been loyal, providing a continuous base of operations at Soto Cano, 60 miles outside of the capital, Tegucigalpa, and supplying troops who are stationed in Iraq. In reward for this loyalty, the military is substantially provided with military assistance from the United States. Unfortunately, this very assistance has bolstered the power of the armed forces against that of civil society. In addition, the courageous efforts of political reformers to subordinate the military to civil government and strengthen the rule of law have been undermined.

On the issue of economic goals, the Honduran government is a party to the Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA), carried out the neoliberal restructuring required by the Millennium Challenge Corporation, and otherwise created a more “hospitable” investment climate. While some Hondurans have benefited from these changes, the poor have suffered from the loss of workers’ rights, lower wages, and poorer working conditions. Unemployment is formally about 28%, the country’s poverty rate continues at over 60%, and Honduras remains one of the poorest and most violent countries in the hemisphere.

Given our longstanding “friendship” with Honduras, it’s time we paid attention to these signs of hardship and misrule. We must reexamine the role that “aid” — both military and economic — has played in fortifying unjust practices by those in charge of the country. If aid to Honduras is to continue — which it undoubtedly will — it should be made contingent upon strict standards of transparency and accountability in the governing process. We no longer have an excuse for ignoring the struggles of this desperate country.