Hundreds of advocates for a more equitable economy will be gathering in Washington, D.C. this coming Tuesday for an all-day conference on “Taxing the (Very) Rich.” Hundreds more will be streaming online and watching as conference speakers explore a variety of bold new proposals, everything from an annual tax on wealth to tax penalties on corporations that pay their top execs unconscionably more than their workers.

Many of these same proposals will then soon likely surface again almost immediately, at next week’s first set of national debates for the Democratic Party’s White House hopefuls. Most of the 20 debaters figure to endorse one — or more — of the ideas that get Tuesday’s “Taxing the (Very) Rich” spotlight.

In other words, we’re shaping up to have a really good week for tax justice. We haven’t had a political climate this open to new initiatives for taxing the super rich since FDR sat in the White House.

All this political momentum, not surprisingly, has America’s flacks for grand fortune more than a little bit worried. They thought they had us convinced that upping taxes on the rich would wreck the economy and penalize “success.” But Americans aren’t buying what the flacks are selling. Our richest owe their “success,” many more of us now understand, to an economy they’ve spent the last four decades rigging.

Serenades to the “successful” are clearly not winning over a deeply skeptical — and cynical — American public. So the flacks are switching gears. They’re doubling down on the cynicism all around us. They’re arguing that taxing the super rich will always be a fool’s errand — because the rich and their armies of lawyers and accountants will always be able to stay a step ahead of Uncle Sam.

So why bother trying to tax the rich, the argument goes, when these deepest of pockets can simply evade whatever taxes Congress imposes? Just accept reality, the flacks implore us. The rich will always stay rich.

That happens not to be true. History shows we can make real progress against grand concentrations of private wealth. We did just that in the mid-20th century, a time when Americans making more than $400,000 a year faced top income tax rates over 90 percent and heirs to grand fortunes had to watch estate tax rates as high as 77 percent carve multiple millions off their inheritances.

In the decades after the Great Depression, these taxes made a huge difference. The share of the nation’s income that went to America’s richest 0.1 percent fell by over three quarters, from nearly 12 percent in the late 1920s to under 3 percent a half-century later. Higher tax rates on the rich can, in short, deliver.

How do flacks for today’s rich explain away this inconvenient history? Yes, the flacks acknowledge, grand fortunes did shrink substantially over the course of the mid-20th century, but taxes on the wealthy, they contend, had little impact on that shrinkage. The mid-century rich as a group, only became less rich because some rich wealthy families squandered away their fortunes on frivolities.

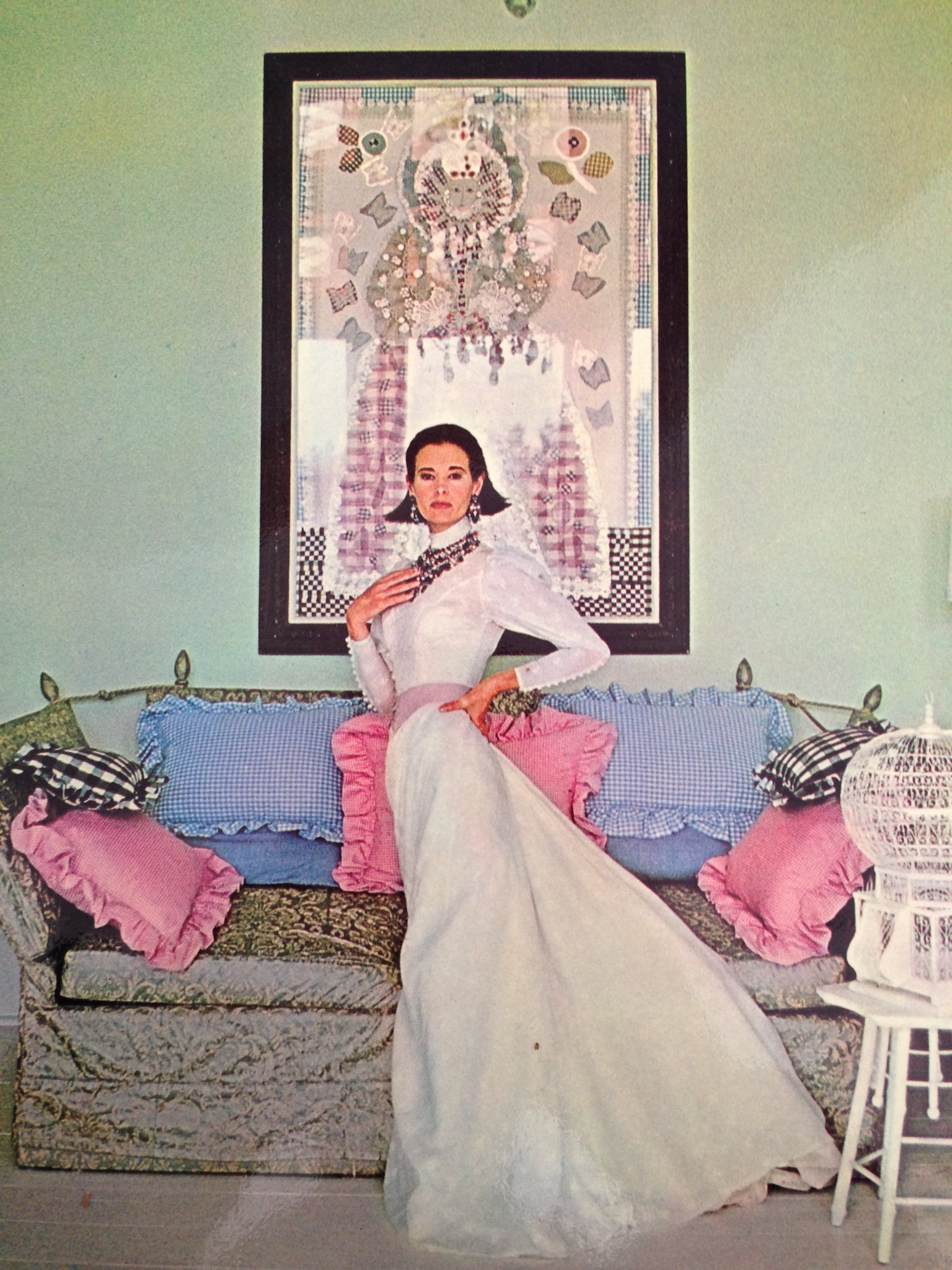

Enter into our story here Gloria Vanderbilt. Or rather, to be more precise, exit Gloria Vanderbilt. This most dashing symbol of the grand Vanderbilt fortune passed away June 17 at a century-spanning age of 95.

Back in the mid 1800s, Gloria’s great-great-grandfather Cornelius ranked as by far the richest single individual in the United States. At one point the “Commodore” had “amassed more money in his personal coffers” than all the money in the U.S. Treasury. But his heirs, the conventional wisdom tells us, wasted away his fortune, eventually leaving poor Gloria and her son Anderson Cooper, the CNN news anchor, with a fabled family history but precious little serious wealth.

One Vanderbilt heir would spin this yarn into a book that exposed “the amazingly colorful spenders who dissipated such a vast inheritance.” The Vanderbilt dollars would “turn to dust,” as another chronicler would put it, squandered away on paintings from Old Masters, getaway homes in Rhode Island, and 10 mansions on Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue. One of these mansions, the New York Times reported in 1926, had a bathroom so big a taxi could turn around inside it.

The Commodore’s heirs, sums up one wealth management executive, did their constant best “to outdo each other.”

“They set and followed the trends of New York’s high society,” Will Bonner of the Bonner & Partners Family Office goes on to add. “They gave money away to fashionable charities. They held over-the-top fairytale parties. They raced yachts, sports cars, and horses. They indulged their fantasies.”

And those indulgences did them in. The introduction of income and estate taxes “no doubt” took a toll, analysts like Bonner acknowledge, but the Vanderbilts “simply spent their money” away.

Various Vanderbilt heirs over the years have certainly squandered. But the Vanderbilts — and their fellow ultra wealthy — don’t owe their fall from super-rich grace to bingeing on baubles. They owe that fall to the stiff tax rates on the rich in effect throughout the middle of the 20th century.

How do we know that squandering didn’t do the rich in? For starters, grand fortunes shrunk across the board in the mid-20th century. Both the sober and the squalid became significantly less rich as high taxes on high incomes reshaped America’s economic landscape.

One example: The plight of the Rockefellers, the only wealthy family that — over the long haul — has rivaled the Vanderbilts in our public imagination. The Rockefeller clan has certainly had its occasional bon vivants, but the family as a whole has maintained a much more fiscally “respectable” reputation. Yet the Rockefellers also spent the mid-20th century watching their grand fortune become less grand.

Remember Nelson Rockefeller, the long-time governor of New York and candidate for the Republican presidential nomination? “Rocky” never did win the GOP’s presidential nod. But President Gerald Ford did tab him as his vice-presidential successor after Richard Nixon’s resignation — and Ford’s subsequent elevation to the presidency — created a VP vacancy in 1974.

The GOP insider who vetted Rockefeller for the Ford White House, a lobbyist named Tom Korologos, began his vetting by asking Nelson the eternal $64,000 vetting question: Anything embarrassing in your background?

“I’ve got something to worry about,” Rockefeller reluctantly informed Korologos, who years later would recount the exchange to the Washington Post.

“His concern was that when it became public, he wasn’t going to be as rich as everybody thought he was,” Korologos told the Post. “He was going to be embarrassed among his peers that he didn’t have all the billions people thought.”

Mid-century America still had, to be sure, some people as rich as Nelson Rockefeller desperately wanted to be. But these would be rich people of a particular sort. In a 1969 book, New Yorker writer Kenneth Lamott gave these rich a name. He would call them “the Income Tax Rich.” You couldn’t enjoy a great private fortune at mid-century America, Lamont explained, unless you had a privileged relationship with America’s progressive tax system. You either had to have inherited your fortune from a time before taxes in the United States became steeply progressive. Or you had to have been doing your business in an industry — like oil — that shielded you from America’s steeply graduated tax rates.

The nation’s titans of “Big Oil” had that shield. They enjoyed a variety of special tax breaks — the notorious “oil depletion allowance” among them — that powerful politicians like Lyndon Johnson and long-time House speaker Sam Rayburn had spent decades protecting. A 1957 listing of America’s wealthiest in Fortune, the nation’s premiere business magazine, would illustrate just how effective these protections turned out to be. Fortune found only one contemporary American with a net worth over $700 million: the oilman J. Paul Getty.

In 1982, just a year or so into the explosion of inequality that Ronald Reagan’s 1980 election unleashed, Forbes magazine published its first annual list of America’s 400 richest. No economic sector had more moneybags on that inaugural Forbes 400 list than Big Oil, with 89. The next richest sector, real estate, contributed just 63 fortunate souls to the 1982 top 400.

The benefits from Big Oil’s preferential treatment at tax time became even more evident at the top of that first Forbes list. Only 13 billionaires appeared on the inaugural Forbes list of America’s 400 richest residents. Nine of these 13 billionaire fortunes rested directly on oil.

By 1982, America’s steeply progressive tax system had already begun becoming considerably less progressive. In the 1960s, the federal tax rate on income in the nation’s loftiest top bracket fell from 91 to 70 percent. In 1981, Congress dropped this top tax rate from 70 to 50 percent. The rate would fall to 28 percent a few years later, then bounce around a little before settling in at the current 37 percent.

The impact of these and other tax cuts on rich people’s fortunes? In 1982, America’s wealthiest needed a net worth of $75 million to enter the ranks of the Forbes 400, the equivalent of about $195 million in today’s dollars. The threshold to enter the 2018 Forbes 400: $2.1 billion.

In other words, between 1982 and 2018, the price for entering the ranks of the nation’s richest 400 rose — after taking inflation into account — well over 10 times over.

Lower taxes on the wealthy, to be sure, don’t explain all the reasons behind this enormous concentration of American income and wealth. Other factors — most notably the steady weakening of the labor movement — have also significantly impacted the nation’s tilt to the top.

But profligacy — of the sort assigned to the Vanderbilt family — plays no significant role here. Today’s fabulously wealthy are squandering just as profligately as their counterparts in days gone by. Their yachts stretch longer than football fields. Their private jets take their kids out on birthday parties. Their dogs wear bejeweled jackets.

And none of this profligacy matters. Our rich continue to get richer. The good news? We know how to slow their merry-go-round. Tax ’em!