At a party before the New York City screening of Che, director Steven Soderbergh said the reason he stretched Che to 257 minutes was because there was just too much story to tell about the revolutionary in a mere two hours. Later, at the same party, I asked a seasoned journalist and avid film viewer (who had just seen Che)his reaction to the film. While he enjoyed the film on the whole, to him it seemed that the jungle scenes were repetitive, ultimately making the film too long. Having now seen the full four and a half-hour film I can attest that, while their opinions are disparate, both Soderbergh and the journalist are right.

At a party before the New York City screening of Che, director Steven Soderbergh said the reason he stretched Che to 257 minutes was because there was just too much story to tell about the revolutionary in a mere two hours. Later, at the same party, I asked a seasoned journalist and avid film viewer (who had just seen Che)his reaction to the film. While he enjoyed the film on the whole, to him it seemed that the jungle scenes were repetitive, ultimately making the film too long. Having now seen the full four and a half-hour film I can attest that, while their opinions are disparate, both Soderbergh and the journalist are right.

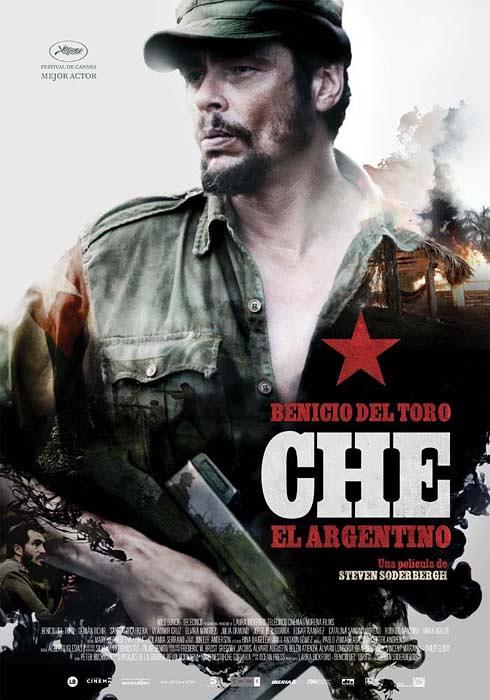

Che opened in limited release as one film on December 12, and will run as two films in January. It begins essentially where the last cinematic Che hit, The Motorcycle Diaries, left off. In that film, before Ernesto Guevara becomes Che, we witness the transformation of a naïve young man into a worldly Bolivarian. He has aspirations of uniting the South American continent, and realizes militant revolution is the only way to do so. Fans of the camaraderie, expansive cinematography, and adventure found in Diaries will appreciate the film’s Part One. Part Two is a decidedly different movie altogether. Che is essentially two movies joined at the hip, but both offer intriguing portraits of the man on the ubiquitous t-shirts.

Che begins in Mexico at a small dinner gathering where young revolutionaries, namely Fidel Castro (Demián Bichir) and Ernesto “Che” Guevara (Benicio del Toro), decry the injustices of imperialism and capitalism, and lay the groundwork for the 26th of July Movement to overthrow Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista. Four and a half hours (and one decade) later the film closes with the execution of Che in a remote, Bolivian village, having failed to foment another Latin American revolution. Not everything that Che partook in, however between these episodes is covered in Soderbergh’s sympathetic hagiography.

Day-to-Day Guerilla Existence

At length, Che covers a lot of ground while at the same time staying very focused. This is apparently the combined vision of Soderbergh and screenwriter Peter Buchman. The film narrows in on two major journeys of the rebel’s life: the revolutionary struggle, and ultimate success, in Cuba, and the limited, guerrilla war in rural Bolivia. In doing so, we are treated to the minutiae of day-to-day guerilla existence. We see, for instance, glimmers of revolutionary training — basic education of illiterate peasants-cum-fighters, the sharing of communal meals, rifle training, and of course, combat. While there’s enough action to be engaging and sometimes thrilling, Soderbergh does so without being too”Hollywood” or over the top.

More than anything, Che romanticizes the revolutionary struggle. The film leans heavily on the “band of brothers” camaraderie of a revolutionary movement on the front lines. Such maneuvering is partly why the symbol of Che has become a worldwide fetish. The way the man handles a cigar, his smoky voice, his sharp mind, and the casual, combat chic of his guerilla attire make him an all around attractive figure, no doubt. But we’ve always known there was more to the man than just iconography.

Part One of the movie follows Che and his comrades as he battles his way from southern Cuba to Havana, winning the hearts and minds of the Cuban people along the way. This section is intercut with grainy, black and white footage of Che delivering a bombastic speech at the United Nations General Assembly and an interview (via translator) with a Western journalist. The back-and-forth between narratives provides welcome relief from the incessant fighting in Cuba while providing insight into the philosophical justifications from which Che and Castro launched their popular movement.

Part Two picks up in Bolivia — entirely skipping Che’s time in the Cuban government, his half-world tour, and his failed revolutionary exploits in the Congo. Very quickly we are taken from one Latin American fight to another. Whereas the screen was shared amongst a wide array of characters in the first half, Part Two is much more insular — the drive of the second half is less about a revolutionary fight and more about a man trying to keep a movement and its spirit alive. And so, while we are treated to polemical tangents in Part One, these deviances are sorely missing from Part Two. Soderbergh replaced the cutaways of Che spitting angrily at Americans and complicit Latin American leaders in the UN with lengthy asthmatic attacks. The screen is taken over by Che’s giant personality, but the viewer is left without much political or philosophical context.

Benicio del Toro as Che is, in a word, perfection. Within minutes of the start of the film’s first half, I had completely forgotten I was watching an actor instead of the real Marxist fighter. Few actors work harder than del Toro in digging deep into the psychology of their characters, and here it pays off. Del Toro’s interpretation brings the guerilla down from the cloud he occupies in the minds of anxious youth worldwide to this earthly plane. We see that Che is mortal — he wheezes through his revolutionary adventures. He makes tactical mistakes in Bolivia. His beard is patchy and scraggly. We are given the impression that we all have within us the ability to be revolutionaries.

But we’re also reminded that revolution is not easy, fly-by-night work. It also takes more than just sheer will and persistence — del Toro finds whatever flame burned within Che and carries it high for the entire saga. This is difficult work for a complex man that simultaneously represented an army of many, and an army of one.

What’s Missing

In light of the gravitas of Che’s personality, his worldwide fame, and the charged politics and tactics he espoused, there is, surprisingly, a lot missing from Soderbergh’s epic. For starters, while we’re shown sympathetic views of fair and just treatment by Che and his comrades of peasants caught in the fighting in Cuba and Bolivia, one of the more controversial aspects not covered was the ruthlessness with which Che conducted his guerilla campaign, namely his treatment toward traitors, spies and deserters. Che was responsible for the execution of those found guilty of these crimes, and while some debate the morality of such behavior, it’s a strategy advocated by a number of revolutionary movements in search of cohesion (Trotsky’s actions in the Bolshevik Revolution come to mind). Similarly, Guevara’s post-revolutionary role as head of La Cabaña prison and tribunals that tried — and executed — Batista war criminals, gets no mention. Unfairly or not, Che is often demonized for these activities. What’s indisputable is the significance these roles played in his revolutionary ascendancy, yet Soderbergh hardly draws from this material.

Che’s sojourn to Congo (between Cuba and Bolivia) is entirely missing too. So are the times when he held institutional positions in Cuba. Likewise, Che’s personal life, relationship with European intellectuals, Soviet connections, and other elements, are avoided.

One could go on and on, dissecting Che for the historical moments — great and small — ignored by this film. Che Guevara’s life was complex and storied, so we mustn’t entirely fault Soderbergh for these oversights (be they purposeful or not). Some aspects border on unforgivable, however. Greater attention should have been given (and clearer lines should have been drawn) to the CIA’s involvement in Che’s capture and execution. Soderbergh only lightly makes the connection, allowing the audience to draw its own conclusion. Is Soderbergh naïve, or just timid? Nonetheless, had he given due diligence to the man’s life, Che would have been an interminably long film; let’s be thankful for the four-and-a-half hours we have now.

There is an element of real irony at play here. Che would have abhorred the level of commercial success his image has achieved in the world of loathsome capitalism. The realignment of this popular image of this revolutionary, however, may very well depend on the commercial success of a film sold simply with the name Che.

Ultimately, Che is a portrayal of passion and dedication to a revolutionary cause, and should be applauded as such. The film helps us stop seeing Che as a logo, and that’s a welcome reprieve. Clearly, however, there’s more work to be done to truly understand this revolutionary.