I recently returned to my childhood home in India with my siblings for a final walk down memory lane with my elderly mother. As expected, it was a powerfully emotional experience. But in ways unexpected, it brought home to me how our planetary fever — climate change — is inflicting a deadly fever on those least to blame for it.

One of our destinations on this trip was the city of Ludhiana, which houses one of the best medical schools in India, Christian Medical College. My father taught and practiced medicine there for many years. Ludhiana is in the Punjab on the border with Pakistan, and is one of India’s industrial and agricultural powerhouses.

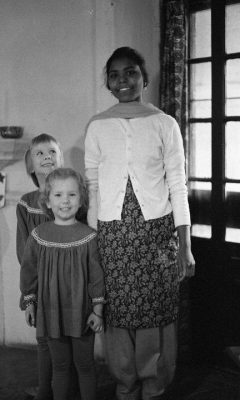

The author with her sister and Parveen.

Some of my earliest childhood memories include my father pushing me on our backyard swing, my nightgown billowing in the warm evening air. I remember him pushing me so high so I could see the flickering oil lamps in neighboring houses. I remember the pungent smell of the dung fires cooking the evening meals in hundreds of homes. The meow of wild peacocks in the fields behind our house, the flocks of chattering parakeets, the evening arguments of crows, the morning dove’s coos on hot summer days. I remember bougainvillea blossoms cascading around our porch in the sunlight, and carrots so fresh from the garden they were like candy. Most fondly, I remember the love of my Indian “ayah,” or nanny. Parveen, only 14 years my senior, helped my parents raise me.

As we stepped off the train from nearby Delhi, we hoped to relive many of these memories. But instead the sky was a gray pall, and the black dust of diesel and coal-fired power emissions coated our nostrils. No amount of filtering the air through our scarves could prevent us from coughing.

Ludhiana is now the fourth-most polluted city in the world, according to the World Health Organization. The water, too, has become contaminated by pesticides, heavy dyes, and other chemicals dumped by industry and leaching into the water table.

The World Bank ranked Ludhiana No. 1 in India in 2009 for creating a friendly business environment. We saw evidence of this at our hotel: foreign businessmen meeting in the lobby, negotiating business deals on couches and in corners, hovering over laptops. Well-heeled Indian women idled away the hours eating expensive lunches in the hotel’s restaurant, trading gossip and playing bingo.

This once relatively small industrial town has become a magnet for global markets — car parts for Mercedes Benz, BMW, and other automakers are produced here, as well as a good share of Asia’s bicycles and many other heavy industrial goods. Much, if not all, of that manufacturing is powered by coal.

Over a home-cooked meal, our former ayah, Parveen, told us that while the pollution was bad, Ludhiana was now experiencing something more frightening: a huge rise in severe dengue.

Dengue — or “breakbone fever” as it’s known for symptoms that include extreme pain in the joints — is the relatively harmless cousin of severe dengue. Prior infection with dengue is one of the risk factors for the onset of severe dengue, which can involve bleeding internally — including from the lungs — and from the nose and gums. The disease, previously known as dengue haemorrhagic fever, can be fatal.

Scientists have warned about the spread of mosquito-borne diseases such as malaria and dengue if we don’t rein in our fossil fuel emissions. By the end of the century, over half of the world’s population — including parts of North America — might be at risk from these diseases.

As we left on the next day’s train, I thought of the record flooding in nearby Pakistan — with substantial portions of the country under water for two years running. I looked out the window and saw train car after train car piled high with black, pulverized coal. And I thought of the woman who unhesitatingly loved me when I was young and how our peoples were now joined in a feverish race of consumption, now bringing ever more mosquitoes to her doorstep on the warm Punjabi winds.