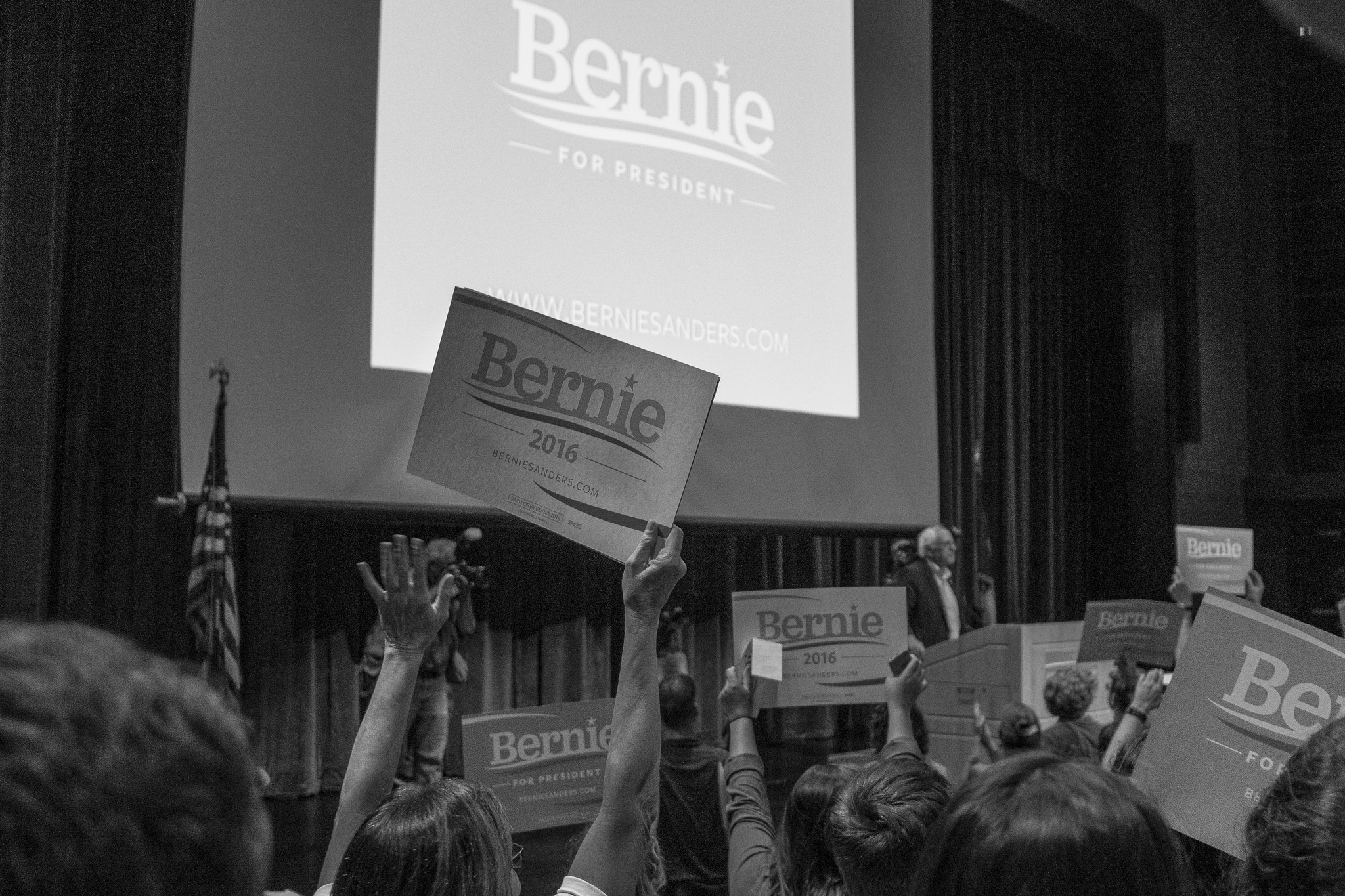

(Image: Flickr / Phil Roeder)

Even though we are still months away from the Democratic primary, it can’t be denied that Bernie Sanders is dominating both the progressive and conservative media circuits. Everyone is focused on the same question: can a small town Vermont senator capture the votes of a discontented nation and translate his popularity into a real victory against Hillary Clinton?

Regardless of his chances to clinch the Democratic nomination, Sanders is already using his growing popularity to shift the progressive debate. Through raising up issues like a financial transaction tax and campaign finance reform, Sanders is forcing Clinton to acknowledge and respond to problems within our economic system that are rarely debated in the primary.

While Sanders’ emphasis on economic reform is welcome and needed, some progressive voters are frustrated by Sanders’ relative silence on two other important issues for 2016: structural racism and climate change.

To force Hillary Clinton to respond to these issues and appeal to minority voters who increasingly care about the environment, Bernie must come up with a policy agenda grounded in these concerns.

Sanders could tackle both of these in one issue: environmental justice.

Hot off the heels of the March on Washington, civil rights protestors turned their eye to the environmental component of racial injustice. Nowhere was this issue more visible that in North Carolina’s Warren County—a rural, poor, primarily black county—which was chosen as a dumping ground for 6,000 truckloads of toxic soil. Activists and organizers rallied together in protest, but they ultimately lost the battle.

However, the situation linked the issues of environmental degradation and racism, giving birth to the modern environmental justice movement.

Dozens of similar incidents arose over the decades, promoting Congress to introduce an Environmental Justice Act in 1992. Despite the EPA’s ongoing focus on this issue, environmental injustices have continued unabated.

Although the movement has been around for decades, I only recently became aware environmental justice. I became interested in the movement after working on an urban farm in the Dudley neighborhood of Boston, which previously served as an illegal dumping group for the city’s unwanted waste. After observing the decades long struggle that Dudley went through to remediate land and make their gardens, homes, and schools safe from dangerous lead contamination, I began drawing connections between the locations of environmental disasters and the communities that were hit first and worst by subsequent hurricanes, oil spills, and air pollution.

The natural disasters are indiscriminate, but the government’s responses are far from it.

Take for instance the 2010 BP oil spill in which close to 5 million barrels of oil decimated the coastlines and economies of Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida. Once oil waste is collected from an oil spill, it has to be dumped somewhere. Despite the fact that people of color make up only 26 percent of the coastal counties in these states, six out of nine EPA approved landfills to collect oil waste were located in communities where the percentage of people of color was far greater than the percentage of people of color in the entire county.

And environmental injustice in America isn’t just about the dumping of waste.

A 2005 Associated Press study confirmed that black Americans are 79 percent more likely than whites to live in neighborhoods where industrial pollution could pose the greatest health threat, and that residents in these neighborhoods tended to be poorer, frequently unemployed, and less educated in comparison to the rest of the country. Exposure to chemicals in the air can lead to increased instances of respiratory issues, childhood asthma, and cancer.

Considering these facts, it’s shameful that environmental justice has rarely been on a policy agenda—let alone discussed as a core concern during presidential campaigns.

Environmental justice is an issue at the intersection of environmental degradation, racism, social justice, and economic inequality, which presents a compelling opportunity for any candidate with a truly progressive agenda.

Sanders has what it takes to be that candidate.

Sanders has given voters a brief taste of his stance on the environment by supporting tax breaks for renewables and opposing offshore and arctic drilling but has failed to substantiate his policy. Though he has tried to galvanize minority voters, his comments during this month’s Netroots conference indicates he’s not quite there yet. At this conference, Black Lives Matter activists read the names of black women who have died in police custody and asked for policy plans to tackle structural racism. Sanders upset activists by whitewashing racial issues in America as primarily products of economics and class.

But Sanders is now showing he’s willing to make amends.

Since Netroots, he has acknowledged Sandra Bland’s death as yet another unacceptable example of police brutality. He recently spoke at the Southern Christian Leadership Council, an organization with deep roots in the civil rights movement. At the conference Sanders provided policy prescriptions to fight mass incarceration and a corrupt criminal justice system, retrain police officers, improve educational opportunities for blacks, and make health care a basic right in America.

While these plans are a positive departure from his botched Netroots conference speech and reaffirm his commitment to ending structural racism in America, he missed an opportunity by not speaking to environmental injustice—an insidious driver of structural racism.

He’s doing better, but he’s still got a long way to go.

Sanders should address the issues of dumping contaminated waste in black communities, moving towards independence from fossil fuels to ensure that climate change does not hit marginalized communities first and worst, and creating green jobs that employ out of work and formerly incarcerated individuals.

Had he addressed these points, he could have outlined a comprehensive plan to address both structural racism and climate change.

As long as politicians continue their refusal to speak to the intersection between the environment and race, structural racism will continue to undermine any efforts to prevent climate change, and environmental injustices will prevent us from moving closer to racial equality.

Sanders has already proven himself to be a maverick in the progressive movement, but in order for his campaign to achieve its full potential as a transformative force in politics, it must acknowledge the prevalence of environmental injustice and pave the way forward for tackling it.