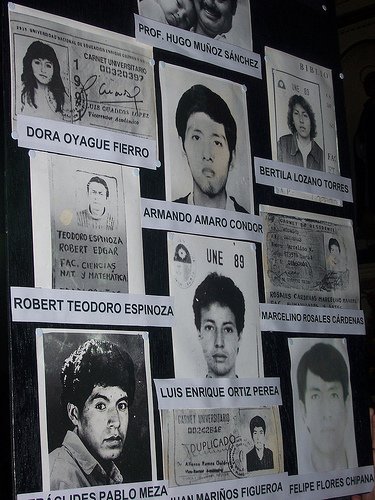

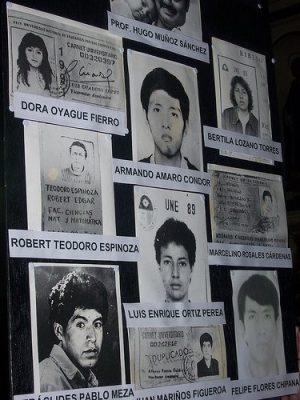

On January 3, 2010, the Peruvian Supreme Court handed down its decision to uphold the April 2009 conviction of former Peruvian president Alberto Fujimori (1990-2000) for four cases of human rights violations. “My son must be very content, as I am, with the judges’ ratification [of the verdict],” said a visibly moved Raida Cóndor in a press conference the morning the ruling was made public. Raida’s son, Armando Amaro Cóndor, was one of the nine students that the Colina Group death-squad kidnapped from their dorm rooms at the Cantuta University and brutally killed in July 1992. “God does exist, and it is He who has given us the strength to persist in this struggle.” Gisela Ortiz, whose brother Luis Enrique was also one of the Cantuta victims, reminded her compatriots just how long a struggle it has been: The confirmation of the verdict represents the culmination of nearly two decades of searching for truth and justice by the family members of the victims.

On January 3, 2010, the Peruvian Supreme Court handed down its decision to uphold the April 2009 conviction of former Peruvian president Alberto Fujimori (1990-2000) for four cases of human rights violations. “My son must be very content, as I am, with the judges’ ratification [of the verdict],” said a visibly moved Raida Cóndor in a press conference the morning the ruling was made public. Raida’s son, Armando Amaro Cóndor, was one of the nine students that the Colina Group death-squad kidnapped from their dorm rooms at the Cantuta University and brutally killed in July 1992. “God does exist, and it is He who has given us the strength to persist in this struggle.” Gisela Ortiz, whose brother Luis Enrique was also one of the Cantuta victims, reminded her compatriots just how long a struggle it has been: The confirmation of the verdict represents the culmination of nearly two decades of searching for truth and justice by the family members of the victims.

In the original verdict, a unanimous decision, the court argued that the gravity and extent of the crimes warranted the imposition of the maximum penalty by law of 25 years in prison. The judges noted that although Fujimori was convicted of crimes codified in Peruvian law — aggravated kidnapping, homicide, and assault — these constitute crimes against humanity according to international law.

The trial of Alberto Fujimori was a milestone in the struggle against impunity in Peru, setting a new standard for the Peruvian courts. It’s the first time that a democratically elected head of state in Latin America has been found guilty of crimes against humanity. It’s also the first time that a former president has been extradited to his home country to face human rights charges. Other trials against former heads of state, such as Liberia’s Charles Taylor or Serbia’s Slobodan Milosevic, were carried out in internationally constituted courts. With the Fujimori verdict, Peru has established an important precedent: National governments can hold their former leaders accountable and not even a former head of state is above the law.

Fujimori’s Decade in Power

By the time Fujimori took office in 1990, the Shining Path guerrilla movement was advancing at an alarming rate despite being repudiated across the political spectrum for the widespread use of terrorist tactics, particularly assaults on unarmed civilians. The Peruvian state resorted to terror to combat the insurgency, resulting in widespread human rights violations, including massacres, forced disappearances, assassinations, and the massive use of sexual violence and torture. According to the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 69,000 Peruvians perished between 1980 and 2000 as a result of the armed conflict.

Not long after taking office, Fujimori’s authoritarian tendencies became evident. In the April 1992 autogolpe, or self coup, he closed congress, suspended the constitution and took over the judiciary with the backing of the armed forces and other powerful elites. With the assistance of de facto security adviser Vladimiro Montesinos — who has subsequently been convicted of numerous crimes, including corruption and arms trafficking, with several other human rights cases still pending — Fujimori established control over virtually all government institutions, including the armed forces, the intelligence services, judiciary, and eventually the Congress. Bribery and intimidation gave the government control over significant sectors of the media and was used to attempt to silence political opposition and civil society groups.

Although a new constitution allowed for Fujimori’s reelection in 1995, considerable national and international condemnation greeted his third unconstitutional reelection bid in 2000. With election observers pointing to widespread fraud, Fujimori won — but his power base began to crumble shortly thereafter. Within months he fled to Japan, faxing his resignation to congress, which declared him unfit to serve as president. Leading opposition congressman Valentin Paniagua was named interim president, and thus began Peru’s difficult and often fledgling democratic transition.

An Exemplary Trial

Throughout this period, Peru’s vibrant human rights community fought hard for justice. It was at the forefront of efforts to confront impunity, end the Fujimori dictatorship, and establish a Truth and Reconciliation Commission. The family members of the victims of violence played a particularly important role in showing the human cost of the civil conflict and refusing to be intimidated in their demands for justice. They traveled to Japan to convince the government of the need to extradite Fujimori, a request that went unheeded. When Fujimori inexplicably left his safe haven in Japan for Chile in November 2005, they mobilized quickly to seek his extradition. Two years later, the Chilean Supreme Court ruled to extradite Fujimori, setting a major precedent for global justice efforts.

The charges against Fujimori were grouped into three different public trials, as well as one summary trial. He has been found guilty in all four trials. In the summary trial, he was found guilty of usurpation of authority for authorizing and participating in an illegal raid on the home of Montesinos’ wife in 2000, presumably to secure and remove compromising evidence, and was sentenced to six years in prison (which was upheld on appeal). Hoping to avoid full public disclosure of corruption and other misdeeds during his government, Fujimori pled guilty in two other trials involving criminal activity and corruption including bribing opposition congressional leaders, wiretapping members of the opposition, media, and human rights activists, misuse of state funds, and a multimillion-dollar payoff to Montesinos to buy his silence.

The case that garnered world attention was the human rights trial that began on December 10, 2007, and centered on four notorious cases: the Barrios Altos massacre of 1991, in which 15 people were killed and four gravely wounded; the disappearance and later killing of nine students and a professor from the Cantuta University in 1992; and the kidnappings of journalist Gustavo Gorriti and businessman Samuel Dyer in the aftermath of the April 5, 1992 autogolpe. The Colina Group, a clandestine death squad that operated out of the Army Intelligence Service and whose purpose was to eliminate suspected guerrilla sympathizers, carried out the killings of Barrios Altos and Cantuta.

After 16 months of judicial proceedings, a special tribunal of Supreme Court justices determined that there was strong and compelling evidence of Fujimori’s direct and leading role in the creation of the criminal apparatus — the Colina Group death squad — that carried out these crimes. Of particular significance, Fujimori was convicted of autoría mediata, which in Peruvian law is attributed to those who have the power to order and direct the system and individuals who commit crimes, or in this case, human rights violations. The tribunal also specifically stated that it considered the four cases of human rights violations to be “crimes of state,” as well as “crimes against humanity.” The latter is particularly significant, since in international law, amnesties or pardons are inapplicable in such cases.

The trial of Fujimori was an exemplary process, setting a new standard for Peruvian courts. It clearly met the international standards for a fair, independent and impartial trial. Fujimori’s due process rights were guaranteed — he had ample opportunity to defend himself in a court of law — and the trial was conducted in a transparent and open manner. The sentence itself was widely hailed as exceptionally thorough, complete, and analytically sound, which made it very difficult to overturn on appeal.

International and National Implications

The final verdict in the Fujimori case comes at a time when judiciaries across the region are struggling to end decades-old impunity and to promote justice, accountability, and the rule of law. Ongoing human rights trials in Chile have led to the conviction of over 200 individuals and hundreds more are being prosecuted or are under investigation. In Uruguay, judges are seeking creative ways to work around the “Expiratory Law,” an amnesty for all police and military personnel responsible for human rights violations during the military dictatorship. Although the law was upheld in a recent referendum, about 20 human rights cases are working their way through the courts, including a major trial against former dictator Juan María Bordaberry for political killings committed during his government in the mid 1970s. And in Argentina, more than 1,400 cases of crimes against humanity are in process — with significant public backing. These courts can now look to the Fujimori verdict for guidance in applying both domestic and international law.

In Peru itself, although the Fujimori verdict sets an exceptional precedent, it remains to be seen what impact it will have on the other ongoing human rights cases. A handful of signficant convictions have been handed down, including the April 2008 conviction of the army general who oversaw the Colina Group operations. But more recent decisions by Peruvian courts resulting in acquittals have contradicted previous jurisprudence on human rights cases. According to human rights advocates, these decisions reflect growing pressure on the part of the armed forces, as well as sectors linked to the ruling APRA party and Fujimori’s supporters, to bring an end to the numerous trials underway.

Endgame?

In the aftermath of the verdict, Fujimori’s defense lawyer, César Nakasaki, claims that he can still obtain his client’s release by presenting a writ of habeas corpus to Peru’s Constitutional Court. Carlos Rivera, one of the lawyers representing the family members in the Fujimori trial, says this is impossible. It would only be allowed if Fujimori’s due process rights had been violated during the trial, which national and international observers agree was not the case.

Fujimori’s supporters continue to float the idea that Fujimori could still be pardoned — either by sitting President Alan García or by Fujimori’s daughter Keiko, if she were to emerge victorious in the 2011 presidential elections — but jurists have noted that there is a double legal impediment to such a course. In domestic law, those convicted of kidnapping cannot be pardoned, while in international law, those convicted of crimes against humanity cannot be pardoned. But, as one blogger noted ominously, “Since when has fujimorismo respected the law?”

This is where the international community can play a crucial role. Following the April decision, the U.S. government issued a statement noting that the “verdict is a powerful statement against impunity, and underscores the importance of the rule of law as a foundation of democratic government.” That message again needs to be made loud and clear. The Obama administration, other governments, and international bodies such as the Organization of American States should send a clear message to the Peruvian government that a reversal of this major advance for justice in Peru and across the world would be repudiated worldwide. International attention remains crucial so that the Peruvian precedent isn’t undone by domestic politics.